Photographing Muslim women: How Sufia Kamal broke the camera taboo

There was a time when taking photographs was considered a sinful act. Even Muslim men rarely dared to stand before a camera. As for women in the inner quarters, the idea of photographing them was almost unimaginable. In such a restrictive era, poet Sufia Kamal defied the frowns of a conservative society and had her portrait taken in a studio. The photograph was taken at the famous C. Guha Studio in Kolkata and published in the women's issue of the monthly Saogat in September 1929. She was 18 at the time, and readers of Saogat knew her by the name Sufia N. Hossain.

The full story of why and how the photograph was taken was recorded by Mohammad Nasiruddin—pioneer of women's awakening and editor of Saogat. The account appears on pages 565 to 567 of his book Bangla Sahitye Saogat Yug. At the time, Sufia Kamal wrote regularly for Saogat, which was then one of Kolkata's most influential literary periodicals. Because her poems appeared in almost every issue, the name Sufia N. Hossain was well known to many—though no-one had ever seen her face. Like other women of her time, she lived inside the home in purdah.

One day, Mohammad Nasiruddin arrived at her house—his first visit there. Sufia's husband, Syed Nehal Hossain, warmly welcomed him into his room. He called Sufia and said, "Come and see who's here." Sufia quickly arrived, greeted the editor, and exchanged pleasantries. The editor said, "I want to publish a women's issue of Saogat, featuring the writings and photographs of Muslim women. For that, I need a photograph."

Sufia replied, "But I've never had one taken."

Hearing Nasiruddin's plan, Nehal Hossain was astonished. He said, "Not only Muslims, even Hindu society has never produced a women's issue of any magazine. You're doing something bold in our orthodox society—your courage deserves praise. And about Sufia's photograph—you're the one who made her a poet. If you wish to photograph her, do so. You don't need my permission. That responsibility rests with you. But whatever trouble this creates at home, I shall handle it."

Nasiruddin said, "In that case, you come with us. We'll take her together." Nehal Hossain laughed, "I don't want to diminish the trust and respect we have for you. I won't go—you take her yourself. Bring her home once the photo is done."He turned to Sufia: "Don't delay—go and get dressed."

"I've never photographed a Muslim woman before. If her picture appears in Saogat, will the skin on your back remain intact?" Nasiruddin answered, "We are fighting against these superstitions and rigidities of our society. We will now publish a women's issue of Saogat with photographs."

Nasiruddin took Sufia to College Street, to C. Guha Studio on the third floor of Albert Hall. Seeing Sufia, C. Guha asked the editor, "Who is she?" The editor replied, "She is a poet—Sufia N. Hossain. You may have seen her poems in Saogat." Guha said, "I have heard the name on many lips." Nasiruddin said, "I'll be printing her photograph in Saogat." Guha widened his eyes: "And have you thought about what will happen to you? I know your fanatical society all too well. I've never photographed a Muslim woman before. If her picture appears in Saogat, will the skin on your back remain intact?" Nasiruddin answered, "We are fighting against these superstitions and rigidities of our society. We will now publish a women's issue of Saogat with photographs."

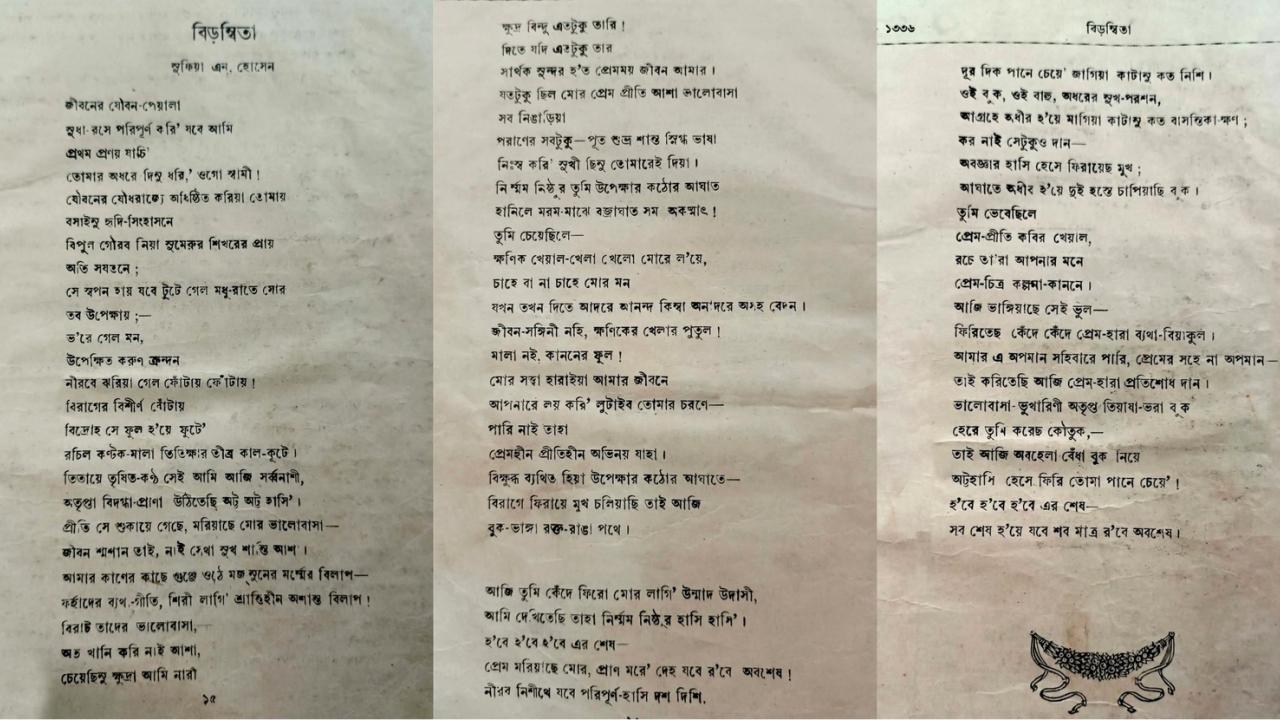

That day, C. Guha took several portraits of Sufia with great care. He did not take payment; instead, he printed the photographs himself and sent them to the Saogat office. The women's issue of Saogat came out in the month of Bhadra, 1336 Bangabda. It featured one of Sufia's long poems, titled Birambita, along with her photograph. Because the magazine published women's photographs, Nasiruddin faced harsh criticism and condemnation. Yet the issue sold in huge numbers. Those who had mocked the magazine but could not find copies in the market flocked to the Saogat office just to see the photographs. Nasiruddin struggled to manage the crowds.

Sufia herself faced no trouble for having her photograph printed, but her poem did create difficulties. Her relatives did not see it as poetry; they interpreted it as the story of her personal life. Wherever the poem expressed sorrow or pain, family members assumed it reflected her private suffering. They began asking what hardship they had caused her for her to write such a poem.

Guided by Nasiruddin's writing, I tried to trace photographer C. Guha. I found a little information in Siddhartha Ghosh's Chhobi Tola: Bangalir Photography-Charcha. I learnt that his full name was Charuchandra Guha (April 24, 1884–November 3, 1957). Later, researcher Tarek Aziz sent me a copy of Charu Guha: Jibon O Alokchitra, published in 2007.

Born in Tegharia village of Keraniganj in Dhaka district, Charu Guha's ancestral home was in Barishal and his maternal home in Hasara, Bikrampur. Among the pioneers who established studio photography in East Bengal, he was one of the most important. In 1908, he opened a studio near Sadarghat in Dhaka—only the third studio in the city after Fritz Kapp Photos and Bengal Studio. He remained in Dhaka until 1916, but the disruptions of the First World War forced him to close the business and move to Kolkata. From then on, this pioneer of studio photography was almost entirely forgotten in his own homeland.

Shahadat Parvez is a photographer and researcher. The article is translated by Samia Huda.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments