Is our city waiting to collapse?

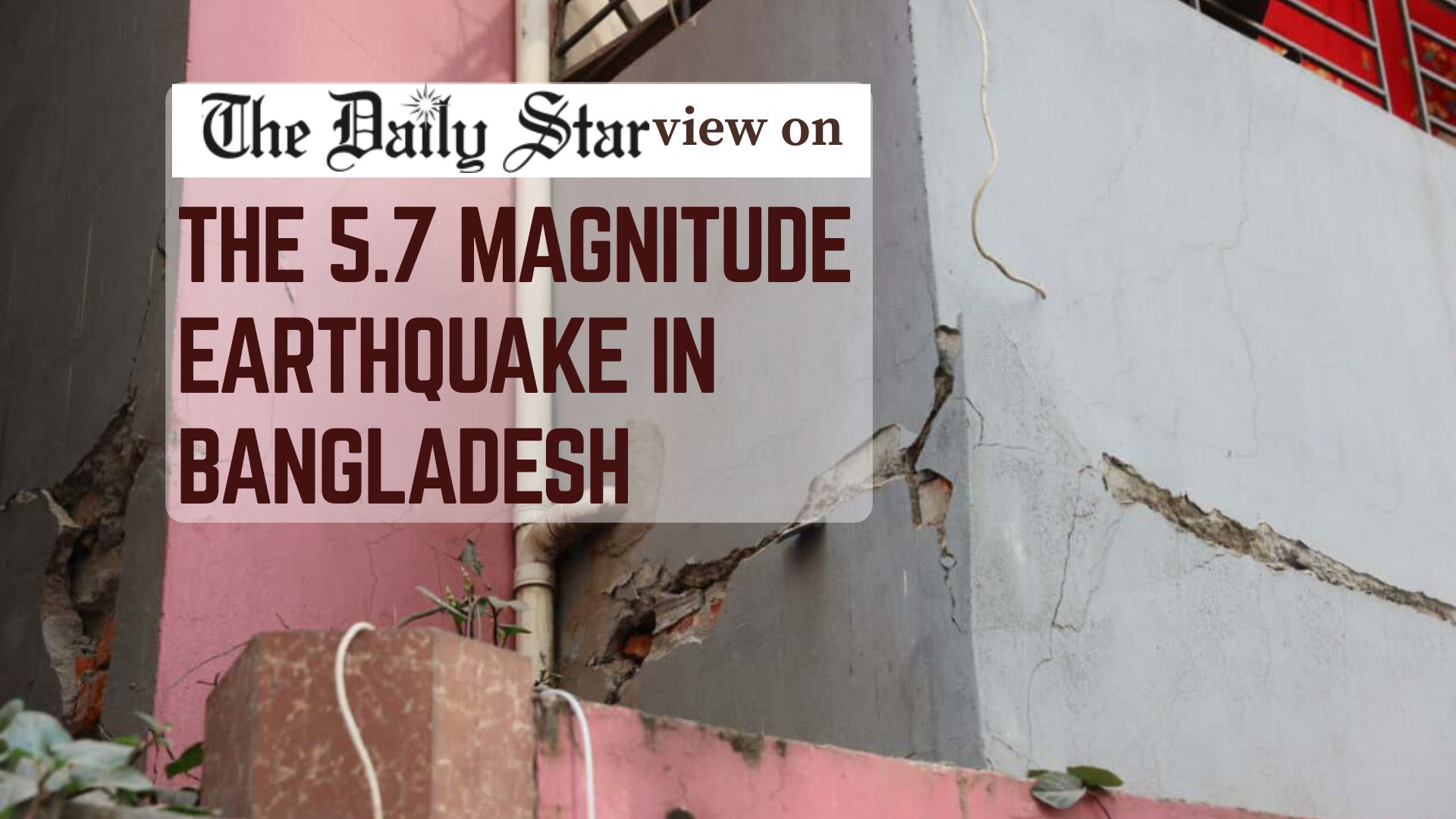

The enemy is no longer at the gates; it is already on our doorstep. It is now anyone's guess when it will finally breach the door. In the wake of Friday's 5.7 magnitude earthquake, a terrifying question has emerged: is the capital built to stand, or merely waiting to collapse? The answer was grimly illustrated in the chaotic warrens of Old Dhaka. There, a railing collapsed, killing three people and raising the total death toll to 10.

The proximity of the earthquake changes the calculus of survival. With an epicentre in Madhabdi, a mere 13 kilometres from Dhaka, the geological threat is no longer distant. It was shallow, releasing its energy close to the surface. Such tremors wreak particular havoc on mid-rise structures—the four-to-eight-storey residential buildings that make up most of Dhaka's urban sprawl, according to experts. These buildings, often constructed on filled wetlands with scant regard for engineering codes, are potential coffins. Historical trends suggest that 7.0 magnitude earthquakes recur in this region every century, and it has been over 100 years since the last one. As a BUET professor has suggested, the geological clock is ticking. A major rupture now could flatten a third of Dhaka city and kill thousands of people.

The tragedy is that this fragility is engineered. RAJUK, the agency tasked with regulating the capital's development, has long functioned more as a facilitator of real-estate chaos than a guardian of public safety. Wetlands have been concreted over. Building rules remain fluid, bent to accommodate the commercial whims of developers who squeeze square footage out of narrow plots. As an expert at the Bangladesh Institute of Planners points out, even the minimum space between buildings is often erased from the final plans.

During a visit to Old Dhaka on Saturday, the chairman of RAJUK offered a dismal diagnosis of urban development. He admitted that developers treat enforcement as a minor inconvenience: when authorities cut utility lines to halt illegal construction, builders simply switch to generators or stolen connections. But his threat to seal the earthquake-damaged Armanitola building if papers are not produced within seven days rings hollow against a backdrop of decades of loose governance. RAJUK's strategy remains reactive, its enforcement porous.

So to minimise devastation after another strong earthquake, the government must embrace both economics and rigour. The RAJUK chairman's suggestion that owners of tiny plots should build joint, legal structures seems to be sound urban economics. Larger plots allow for the necessary engineering tolerances that are physically impossible on smaller parcels of land. But good economics requires good policing. The proposal by experts to introduce third-party verification of building designs, following the model of Indonesia and Thailand, is an essential stopgap for a regulator that has lost its way.

History offers a grim footnote to this urgency as Bangladesh is bracing for something far worse. By a cruel coincidence, Friday's quake occurred on the exact anniversary of the 1997 Chittagong earthquake, which killed several people. But looking back is a luxury. If Friday's was indeed a foreshock, with two subsequent tremors on Saturday, the window for action is closing. The government must immediately mandate inspections of all mid-rise buildings and enforce the "Red-Yellow-Green" safety coding system. To ignore the warning is to be complicit in the disaster to come.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments