How Khaleda Zia approached economic reforms in 2001-06

As the World Bank’s sector director for Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (PREM), I worked very closely on the reform programme in Bangladesh led by former Prime Minister Begum Khaleda Zia in 2001-06. As PREM sector director, I was responsible for managing policy-based lending operations, known as development support credit (DSC). I managed four such credits amounting to over $1 billion, of which the first three were administered during 2003-2005. This lending, along with support from the IMF, was necessary to stabilise the balance of payments.

Below, I provide my analysis of how the reform programme was developed and implemented, and the major outcomes of the programme, with a view to demonstrating that substantial reforms can be implemented with good results under astute political leadership and a strong economic team.

To set the stage for the reforms, in early 2003, my vice-president and I called on Khaleda Zia at her office near the old Dhaka airport. She received us warmly and we had a one-hour conversation on the multiple economic challenges facing her government and the need for far-reaching reforms.

She listened intently as we described these issues and stated firmly that she was committed to implementing all necessary reforms. She said she would empower her finance minister, Saifur Rahman, and his team and provide all required political support. That was a stunning message and a clear signal of her delegated and inclusive management style, which is somewhat rare in today’s mostly autocratic global political leadership.

At the end of our meeting, her principal secretary, Dr Kamal Siddiqui, introduced me to her in Bangla, saying I was the leader of the World Bank’s economic team and the senior-most Bangladeshi staff in Washington DC. She turned towards me and smilingly said, “I am delighted to meet you, and I hope you will keep an eye on our needs.”

Since that meeting, there was no turning back. The Bangladesh core reform team was headed by Finance Minister Saifur Rahman and included Commerce Minister Amir Khasru Mahmud Chowdhury, Bangladesh Bank Governor Dr Fakhruddin Ahmed, Principal Secretary to the PM Dr Kamal Uddin Siddiqui, and Finance Secretary Zakir Ahmed Khan. This was, undoubtedly, an outstanding team of well-trained and seasoned policymakers. They combined academic excellence with sound administrative experience and political savviness—a rare combination these days.

The multi-year reform programme was far-reaching and was grounded in the government’s own poverty reduction strategy paper. The reforms encompassed macroeconomic management, public finance, banking sector, trade policy, public enterprises, public financial management, procurement, public administration, and anti-corruption.

The reform programme was not only comprehensive, but also tough in many areas requiring careful political management. One such sensitive reform was the liberalisation of the exchange rate. In May 2004, I received a phone call from Finance Minister Saifur Rahman, who said local Bangladeshi economists were strongly opposed to the liberalisation of the exchange rate as doing so would destabilise it. Since I believed that this reform was essential to support the expansion of exports, I suggested that I first talk with the Principal Secretary Kamal Bhai.

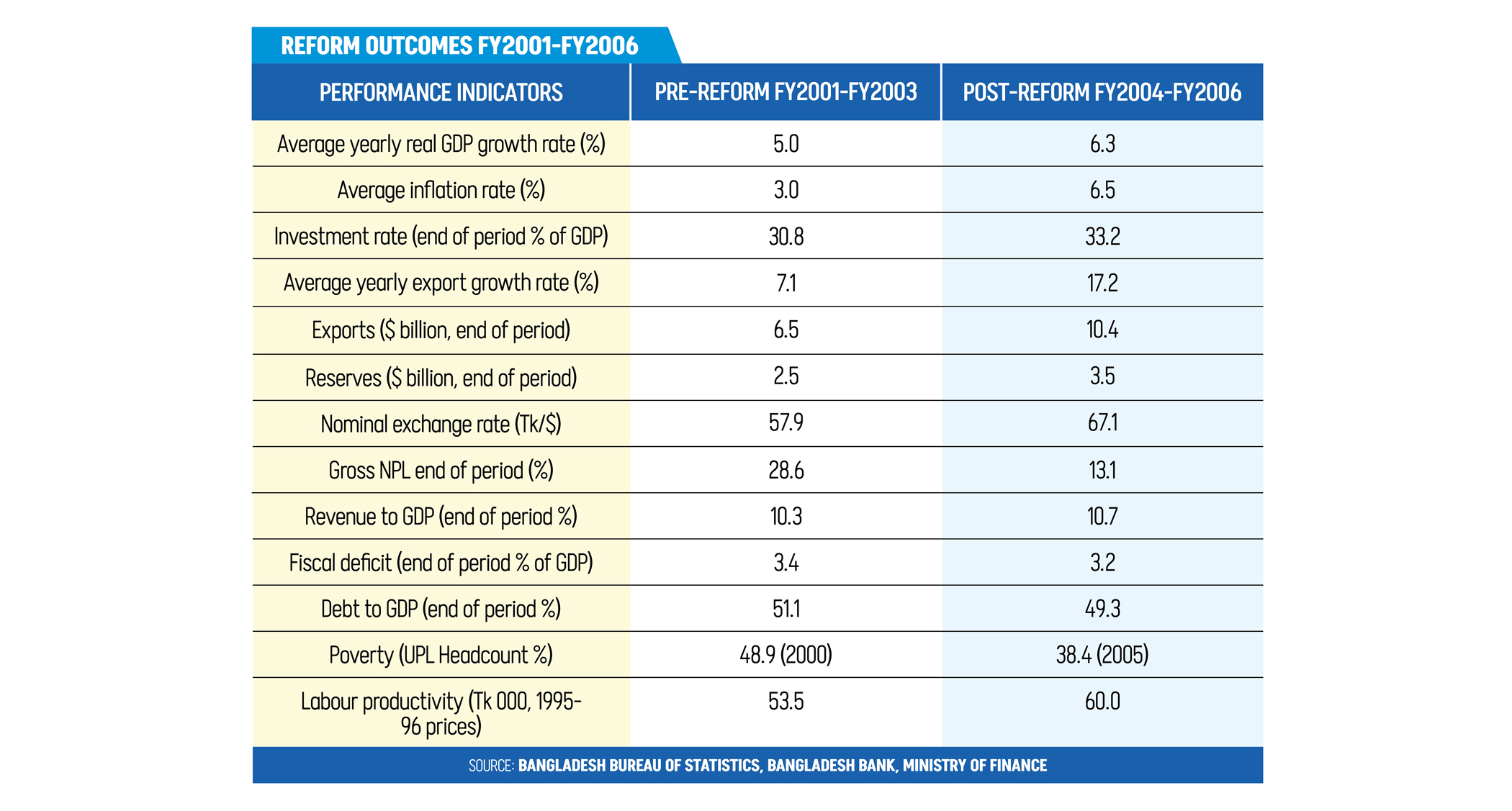

Kamal Bhai promised to brief the PM. I then called the finance minister and briefed him about my conversation with Kamal Bhai. The next day, Finance Secretary Zakir Bhai called to say the PM had approved. This is a strong testimony to Khaleda Zia’s sound leadership. In similar tough situations involving banking, privatisation, and energy pricing reforms, the then PM again provided solid backing to her economic team. This was a remarkable demonstration of her reform commitment and delegated management style. Economic reforms are only meaningful if they yield results. The broad macroeconomic performance in the post-reform period is summarised in Table 1. The evidence paints a remarkable picture of progress. GDP growth expanded by an average of 1.3 percentage points per year, fuelled by increases in private investment and exports. Private investment responded to the deregulation drive in trade and investment. The surge in exports by 17.2 percent was truly remarkable. These laid the foundations for growth of employment and incomes. Average labour productivity expanded by 3.9 percent, supporting the rise in real wages and incomes. Poverty declined by an unprecedented 9.5 percentage points over the five years of 2000-2005.

The macroeconomy was stable despite exchange rate liberalisation. Inflation rate increased owing to taka depreciation and an increase in demand from rising investment, exports and GDP growth. The nominal exchange rate moved from Tk 57.9 per US dollar in FY2003 to Tk 67.1 per dollar in FY2006, amounting to an average depreciation of five percent per year. This re-alignment of an overvalued exchange rate was a critical factor for the surge in exports, which also benefited from trade reforms. But unlike the fear expressed by critics, the exchange rate did not overshoot or destabilise, and inflation hovered around six to seven percent per year.

Fiscal performance also improved as total revenues grew modestly and there was a reduction in subsidies owing to performance improvements in SoEs, energy pricing adjustments, and better management of the power sector. The increase in fiscal space and cutback in subsidies allowed some modest improvements in spending on health, education and social protection.

There was solid improvement in the banking sector as deregulation raised the asset share of private banks and lowered the share of the corruption-infested public banks. The portfolio quality improved dramatically as gross NPLs fell sharply from 28 percent to 13 percent. The number of banks with NPL exceeding 10 percent fell substantially from 21 in 2003 to 12 in 2006.

Moving forward, the main lesson is that only comprehensive and sustained economic reforms hold the key to improved economic performance. A second message is that there is no alternative to a first-rate economic team working seamlessly under the guidance of a strong finance minister. A final message is that astute political leadership is the ultimate key to success. The example set by Begum Khaleda Zia through her uncompromising political support for the reform programme and delegation of responsibilities to a competent reform team seals her place as a core champion of economic reforms in Bangladesh.

Dr Sadiq Ahmed is vice-chairperson at the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI). He can be reached at sadiqahmed1952@gmail.com.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments