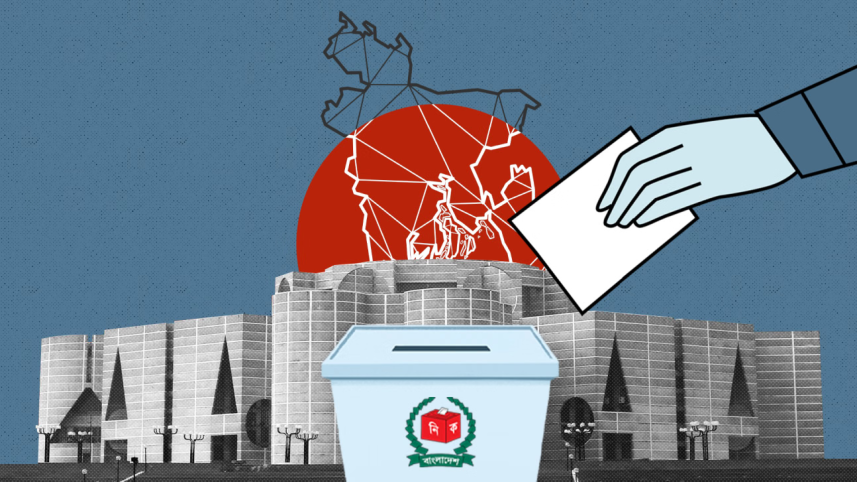

Caretaker government reborn: What challenges lie ahead?

In a sweeping constitutional turnaround that is set to redefine the landscape of Bangladesh's electoral governance, the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court has unanimously reinstated the Thirteenth Amendment, restoring the country's non-party caretaker government (CG) system for future general elections. The full bench, led by Chief Justice Dr Syed Refaat Ahmed, went further still: it declared the Fifteenth Amendment of 2011 — through which the caretaker model was abolished — "illegal" and therefore without constitutional force. With that finding, the Court has effectively rolled back one of the most politically contentious reforms of the past decade and a half. This decision marks the most significant shift in Bangladesh's constitutional order since the turbulent political and judicial wrangling that surrounded the caretaker system's dismantling in 2011.

It also reflects a notable change in judicial temperament. Where the 2011 Appellate Division leaned heavily on doctrine that prized continuity of elected government above institutional neutrality, the 2025 bench has placed renewed emphasis on safeguarding electoral fairness, the integrity of the franchise, and the credibility of transitional governance. By reviving the Thirteenth Amendment in full, the Court has restored a mechanism long regarded — both domestically and abroad — as a stabilising force during election periods. The ruling not only alters the political calculus ahead of future polls but also sets firm constitutional boundaries around the extent to which future governments may reshape the machinery of elections. It amounts to a reassertion of judicial oversight at a moment when the structure and legitimacy of democratic institutions have once again come under intense scrutiny.

Historical background and earlier litigation

The Thirteenth Amendment of 1996 — born of rare cross-party consensus — established a neutral, time-bound caretaker administration tasked exclusively with supervising general elections. Over the following decade, its constitutional legitimacy was repeatedly upheld by the High Court, and three national elections were successfully conducted under its stewardship. For many, the arrangement became an essential safeguard: a structural guarantee of electoral credibility in a politically polarised landscape. This equilibrium was abruptly disrupted in May 2011. A seven-member Appellate Division bench, headed by Chief Justice A.B.M. Khairul Haque, issued a terse and controversial short order on May 10, 2011, declaring the Thirteenth Amendment "prospectively unconstitutional".

In an unusual doctrinal compromise, the Court nonetheless permitted the system to remain in place for "two further elections", ostensibly to avoid immediate institutional instability. The Government, however, moved with striking speed to consolidate the ruling. Within weeks, Parliament passed the Fifteenth Amendment (adopted on June 30 and gazetted on July 3, 2011), which not only excised the caretaker provisions in their entirety but also recalibrated several other chapters of the Constitution. By the end of 2011, a dual process — judicial invalidation and legislative excision — had wholly dismantled the caretaker framework. All subsequent general elections, including those held in 2014, 2018 and 2024, were therefore conducted under incumbent partisan administrations, reshaping Bangladesh's electoral landscape for more than a decade.

Renewed petitions and the 2024–25 constitutional reopening

Mounting political tensions and far-reaching realignments across 2024–25 breathed new life into a legal contest that had lain largely dormant for more than a decade. Emboldened by shifting political winds, a coalition of petitioners — including opposition parties such as the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and Jamaat-e-Islami, supported by a number of prominent civil-society applicants — moved to revive the challenge against the Supreme Court's 2011 Appellate Division ruling. Their petitions sought nothing less than a constitutional re-examination of the earlier decision that had invalidated the Thirteenth Amendment and dismantled the country's non-party caretaker government framework.

It also reflects a notable change in judicial temperament. Where the 2011 Appellate Division leaned heavily on doctrine that prized continuity of elected government above institutional neutrality, the 2025 bench has placed renewed emphasis on safeguarding electoral fairness, the integrity of the franchise, and the credibility of transitional governance.

The constitutional terrain changed decisively on December 17, 2024, when a two-judge bench of the High Court Division delivered a dramatic and consequential judgment — the full text of which was published in July 2025. Spanning 139 pages, the judgment struck down key provisions of the Fifteenth Amendment, holding that Parliament had acted beyond the limits of its amending power when it abolished the caretaker system in 2011. In doing so, the High Court effectively reopened a constitutional pathway many had assumed closed, signalling that the question of caretaker governance remained legally unsettled. This judgment forced the Appellate Division back into the centre of the constitutional debate. In response to multiple applications for leave to appeal, review, and reconsideration, the Supreme Court's apex court empanelled a full seven-judge bench — a measure reserved for issues of the highest constitutional gravity — to rehear the matter in 2025. This set the stage for the most significant judicial reconsideration of Bangladesh's electoral framework since the abolition of the caretaker system more than a decade earlier.

Statement on the 2025 Appellate Division judgment restoring bangladesh's caretaker government

In a sweeping constitutional reversal that will define Bangladesh's electoral architecture for years to come, the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court on November 20, 2025 delivered a unanimous and emphatic judgment restoring the non-party caretaker government (CG) system and overturning its own landmark 2011 precedent. The full bench — comprised of Chief Justice Dr Syed Refaat Ahmed and Justices Md Ashfaqul Islam, Zubayer Rahman Chowdhury, Md Rezaul Haque, S.M. Emdadul Haque, A.K.M. Asaduzzaman, and Farah Mahbub — issued a decision that fundamentally recalibrates the balance between parliamentary authority and constitutional constraints. The Court held that the 2011 short order, which had prospectively declared the Thirteenth Amendment unconstitutional, was erroneous in principle and unsupported by the Constitution's structural logic. In setting aside that decision, the Court revived the amendment in clear and categorical terms, emphasising that the Thirteenth Amendment "stands revived" and once again forms part of the nation's supreme law. This constitutes a rare judicial repudiation of a previous Appellate Division ruling on constitutional amendment powers.

The ruling not only alters the political calculus ahead of future polls but also sets firm constitutional boundaries around the extent to which future governments may reshape the machinery of elections.

The bench further ruled that Parliament in 2011 had exceeded its constituent authority by abolishing the caretaker government provisions outright. The sections of the Fifteenth Amendment that eliminated the CG mechanism were therefore declared "of no legal effect", restoring the constitutional continuity disrupted by the political climate of the early 2010s. The Court unequivocally reinstated the caretaker system as part of the operative constitutional text. However, consistent with reportage from The Daily Star, the Associated Press, and other reliable outlets, the Court made an important temporal limitation: the restored caretaker system will not govern the forthcoming imminent national election.

This caveat ensures administrative stability and avoids mid-cycle electoral disruption, allowing the next poll to be conducted under the current arrangements while re-establishing the caretaker mechanism for all subsequent elections. While the ruling restores the caretaker system's constitutional basis, the Court refrained from prescribing its immediate operational blueprint. It expressly noted that matters such as: the appointment method for the Chief Adviser, the handover and transition timeline, the composition and mandate of the caretaker administration, and the interaction with other post-2011 constitutional amendments, require future legislative action, administrative rules, or further judicial directions. The Court's approach leaves Parliament and the Election Commission with a structured but flexible mandate to craft the transitional architecture.

This judgment — remarkable in its unanimity and its willingness to revisit the Court's own prior constitutional interpretation — constitutes a watershed moment. By reinstating the Thirteenth Amendment and nullifying the contested portions of the Fifteenth, the Appellate Division has re-entrenched the caretaker government as the governing framework for all general elections after the next scheduled poll. It marks a decisive judicial step towards restoring institutional neutrality in the electoral process, signalling a return to a constitutional model that shaped Bangladesh's democratic experience for nearly two decades.

Implications and reactions

The ruling has sent ripples — indeed, near-immediate shockwaves — through Dhaka's political establishment. Opposition parties moved swiftly to frame the judgment as "a restorative act of constitutional justice" (BNP briefing, November 20, 2025), arguing that the Court has finally corrected what they regard as a decade-long democratic aberration.

Government advisers, by contrast, struck a more cautious note, warning that "modalities and transitional questions require urgent attention before implementation" — a signal that the executive is acutely aware of the complex institutional choreography now required. Election administration specialists have already begun sketching the formidable list of operational questions that must be resolved before the caretaker system can function in practice. Chief among these are: the precise timeline for the caretaker administration's assumption of authority; the criteria and nomination process for selecting the Chief Adviser, particularly in light of contemporary political realities; the delineation of powers between a neutral interim cabinet and the outgoing political executive, including safeguards against overreach on either side; the synchronisation of the revived caretaker framework with existing constitutional provisions governing the dissolution of Parliament and the management of governmental continuity.

Legal analysts stress that, although the Appellate Division has now settled the core constitutional question with rare clarity, the judgment does not exhaust the need for political and legislative intervention.

Legal analysts stress that, although the Appellate Division has now settled the core constitutional question with rare clarity, the judgment does not exhaust the need for political and legislative intervention. Parliament — if only to ensure institutional coherence — may yet be required to enact clarificatory provisions, update procedural rules, or establish transitional mechanisms to give practical effect to the reinstated constitutional architecture. The Court has reopened the door, but the responsibility for walking the country through it, they argue, will fall jointly upon the judiciary, the executive, and the legislature.

A constitutional return after fourteen years

Fourteen years after the 2011 judgment that dismantled the caretaker framework, Bangladesh's highest court has dramatically redrawn the contours of the nation's electoral future. By restoring the caretaker model — a mechanism long championed by opposition coalitions and civil society — the Appellate Division has effectively rebalanced the distribution of constitutional authority among the executive, Parliament, and the judiciary.

What was once a settled chapter has been reopened with constitutional force and political consequence. For now, the next general election will proceed under the existing partisan system. Yet the political class confronts an unavoidable new reality: every subsequent national poll will, by constitutional mandate and judicial protection, be conducted under a revived non-party caretaker administration. This marks not merely a procedural shift but a structural recalibration of how electoral legitimacy is to be safeguarded in Bangladesh.

The coming months will be decisive. The restored framework must still be operationalised, its ambiguities interpreted, and its institutional mechanics set back into motion after more than a decade of dormancy. Much will depend on whether political actors — long accustomed to polarised brinkmanship — can manage this transition responsibly, without steering the country towards the very cycle of constitutional confrontation that the caretaker system was originally designed to avert. The judgment has set the direction; the stability of the path ahead now rests with those who must walk it.

Md. Arifujjaman is Deputy Solicitor (Additional District Judge) at the Solicitor Wing of the Law and Justice Division in the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. He can be reached at: arifujjaman.md@gmail.com.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments