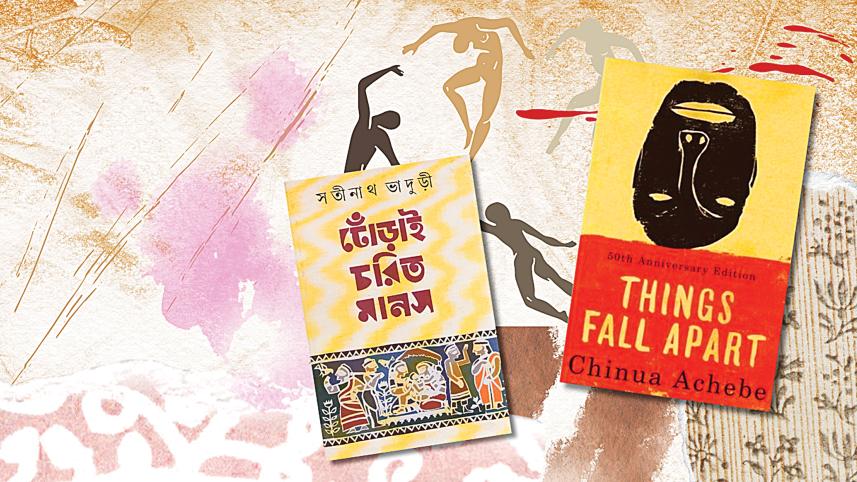

Two awakenings: Reading ‘Dhorai Charita Manas’ and ‘Things Fall Apart’

My readings of the two books—the subject of this write-up—happened to be on two momentous occasions, set two decades apart in utterly contrasting ways. The first was an awakening. The second was… well, also an awakening, albeit in a quite different sense. The two books in question are Satinath Bhaduri's Dhorai Charita Manas (Bengal Publishers,1963) and Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart. Before delving into the "momentousness", let me note one difference between the two occasions.

While reading Dhorai, I felt a quiet solitude in which I stumbled upon a rare gem—one that, though lying in plain sight, had somehow remained hidden amid the vast, anonymous sea of books. My emotion was shared by few—an awakening to the unseen epic that was latent in our own soil. Things Fall Apart, on the other hand, was already riding the glorious, western, shiny crest of the highest wave of worldwide recognition—that brought about a realisation as to how under-translated and under-represented Bengali literature is, even as a similar epic form lived fully in another colonised world.

Back in the mid-90s, Professor Abdullah Abu Sayeed of Biswa Sahitya Kendra sent someone to the BUET campus to fetch me for his newly formed study circle–Biswa Shaitya Chakra, which he described as the echelon of all study circles at Kendra. Among many famous books we read and discussed, Dhorai had the most unassuming title—its rusticity and backwardness perfectly setting up the biggest surprise upon reading.

I remember Ahmad Mazhar's reaction resonating exactly with mine, validating it: "As I was reading this book, I felt an enormous shame—how come I had never even heard of this novel, let alone read it?"

I became an instant admirer of Satinath Bhaduri and soon went on to read his other works—the awe never ceasing to inspire. Yet I carried the unease of being a lonely wolf placing Bhaduri on such a high pedestal, sensing a widespread paucity of his recognition—until one day.

On television, Shawkat Osman was asked about his favourite writer. "You may not recognise him—not someone very well known," he began. "Satinath Bhaduri," he declared. I felt redeemed. Later, of course, I saw Bhaduri's stock begin to rise in our literary society.

As for Things Fall Apart, I first became aware of its celebrated existence soon after moving to the United States, around the turn of the millennium. Web searches for the "top 100 books" kept returning Achebe's title near the top. Intrigued, I made a few attempts to read it, but each was thwarted by other urgencies.

Then, in 2014, after an exhilarating literary discussion with a Brazilian educator of African descent—an excitable client and friend—he expressed shock that I hadn't read Things Fall Apart yet. He insisted I do so immediately, lent me his copy, and extracted a promise that I would finish it within two days. I complied. It set a big rock rolling—a story for another time. What matters here are the thoughts that passed through my mind before that rock was tipped off.

Two decades separated my readings of the two books, yet the memetic gap was bridged instantaneously. So much of Things Fall Apart reminded me of Dhorai Charita Manas. "The absence of author!" That was my first reaction. I had no idea—almost as if by providence—of the writer or person Bhaduri was when I first read Dhorai. The same was true of Achebe when I began Things Fall Apart. Neither author intruded upon the reading experience with their person. In both, the characters are self-sustained, the narration local, the conflicts raw and internally charged. Judgment is not absent but expressed only in the moral idiom of the indigenous. Globality is kept rigorously at bay—spatially and temporally.

If I had not recognised that Gandhi was being referred to as Ganhi Bawa, I would never have known the time period of Dhorai. Not a single mention of the British Raj, if my memory serves. Nor in Things Fall Apart, until the very last leg of Okonkwo's journey. As a reader from a different world, I was equally in the dark about the historical moment of Achebe's tale. This authorial invisibility is perhaps the most significant quality that places these two novels among the highest in the literary canon.

The next recognition was structural. Both heroes are born of uncelebrated backgrounds; both exhibit off-the-shelf heroism; both face mimetic incidents that drive them into exile; both achieve renewed leadership and return home seeking restoration, only to meet inevitable downfall. The parallels are almost architectural. The resemblance made me wonder if one writer had influenced the other. But realising that Things Fall Apart was written nearly a decade later, and that an English-speaking Nigerian could scarcely have encountered an untranslated Bengali novel, I turned to the possibility of historical convergence—the twin consciousness of colonised worlds wrestling with moral collapse.

To expand further on their mirrored odyssey is to find more reflections still. Both emerge from familial backgrounds that epitomise societal vice: the dubious moral circumstances of Dhorai's mother, and Okonkwo's father—a failure within the Igbo value system. Both men strive to transcend inherited shame through the pursuit of dignity and order, only to commit acts that destabilise their moral standing (Okonkwo's killing of Ikemefuna; Dhorai's compromised role in rebellion and violence). Both endure exile and return, their homecomings culminating in futile redemption.

Beyond these parallels lie the more predictable correspondences of two postcolonial masters: the documentation of vanishing indigenous orders, the erosion of spiritual leadership. And, overarching all, a universal phenomenon—the empire as an unseen gravitational force, not a character but a condition—making their tragedies less about conquest than about internal corrosion.

Contrasts are not my subject here, but one deserves mention: the titles. Achebe borrows from a contemporary poem, "The Second Coming"; Bhaduri, by contrast, invokes the archaic and rustic cadence of Ramcharitmanas, a half-millennium-old epic. One gestures outward to the modern world; the other descends into the folk-epic soil of its own.

I often wonder how Dhorai Charita Manas would fare if translated and placed alongside Things Fall Apart in the global run for the great-novel canon. The crowd mind may be unpredictable, but in my private hierarchy, Dhorai would stand a few rungs higher—its quiet moral resonance reaching further than its fame ever has.

Ali Tareque is a Bangladeshi-born writer based in Houston, Texas. He is the author of the English novel Echo of the Silence (Arrow Books/Penguin Random House, 2023) and the Bangla short story collection Sontan o Sonketer Upokotha (Roots, 2022). Alongside fiction, he writes poetry, directs plays and films, and performs elocution.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments