How victimhood distorts our sense of history

Why have we failed to build a strong state, durable institutions, and a shared story of coexistence? I look for answers in the histories we write, or tell ourselves, and the ways they shape our character as a nation. Again and again, we see the same pattern: we often cast ourselves only as victims, rushing to ask who betrayed us or which outside power conspired. The story of victimhood is an uncomplicated one, like a linear film plot: simple to narrate, easy to understand, and comforting to believe. But this unquestioning resignation to an easy story prevents us from asking hard questions about our own role in history and our culpability.

Let us examine the narrative of the Battle of Plassey fought on June 23, 1757. The familiar story is that Mir Jafar betrayed Nawab Sirajuddaula, and that Jagat Seth, Rai Durlabh, and Yar Lutuf Khan sold him out to Robert Clive. This is, however, only a small part of the bigger picture: the Mughal Empire was already collapsing, Bengal's succession after Alivardi Khan was disputed, the administration was weak, the revenue system rotten, the army outdated, and the financial base broken. So the East India Company walked into a house that was already falling down—a house we rarely examine critically because the victim story feels easier to comprehend. While we were playing the victim game, in Europe, Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations (1776) was asking how wealth is produced. At that time, many of our nawabs and zamindars spent heavily on palaces, courts, music, and spectacle, while treating investment in new knowledge, technology, military reform, and proper administration as a side concern, as if old habits were enough to keep up with a changing world.

We also had the sea in front of us, but the idea of kala pani—the belief that crossing the sea would threaten ritual status—shaped social attitudes towards overseas travel. Texts like the Baudhayana Dharmasutra were invoked to support this view, turning overseas travel for trade, education, or politics into a social risk for many high-caste groups. Bengali Muslims, for their part, did not build lasting maritime trade networks either; unlike the Portuguese, Dutch, French, or British, our merchants never created sea-borne trading empires. Their ships came from the other side, and we settled into the role of consumers of those ships and their goods.

We often say the British ruled through a "divide and rule" policy. While they did use Hindu-Muslim, caste, ethnic, language, and regional lines to govern, the cracks they exploited—caste and sub-caste, high and low orders, Ashraf and Atraf, landlord and peasant, town and village—were already there; colonial rule merely fixed them in law through censuses, land laws, and separate electorates. In 1947, we again placed blame on "Hindus" or "Muslims," refusing to explore underlying nuances. The Partition uprooted well over 10 million people and killed several million through riots, hunger, and disease. These outcomes were shaped by decades of communal politics and tensions as well as administrative weaknesses of the two new states. Our textbooks mostly blame "them," but if Muslims killed Hindus and Hindus killed Muslims, the real question is whether we are ready to face our own share of those crimes instead of hiding them.

Pakistan emerged in 1947, but instead of focusing on building institutions, its politics quickly slid into court intrigue. A full constitution came only in 1956; the 1949 Objectives Resolution spoke of Islamic principles, yet little was done to establish stable democratic practices. The Muslim elite used Islam for power, and within two years of that first constitution, Ayub Khan seized control in a coup, suspending the constitution. Many still say "external powers destabilised Pakistan," but the first coup-maker was a Muslim general backed by local elites. At the same time, religious leaders were busy with anti-Ahmadi campaigns: in 1953, they led agitations in Punjab and Lahore that forced the imposition of martial law in Lahore, and in 1974, the Second Amendment formally declared Ahmadis non-Muslim. While we keep repeating that "Muslims are always victims," these developments show how a group of Muslims used law and street pressure to deny another community equal citizenship.

At this point, some may argue, "Oppression was in the cities; the villages were fine." Our imagination of the village remains highly romantic: that rural Bengal is/was peaceful, equal, beautiful. Yet in 1948, speaking at the Indian Constituent Assembly, Dr B.R. Ambedkar described the village as the nursery of localism, ignorance, narrow-mindedness, and communalism, a place where caste oppression was reproduced. This is not only about Hindu villages. In Muslim villages, too, those who have power pressed down on those below. The idea that "the poor are innocent" does not survive close inspection either. When people at the lower rungs gain some power, they are also as likely to oppress those weaker than themselves.

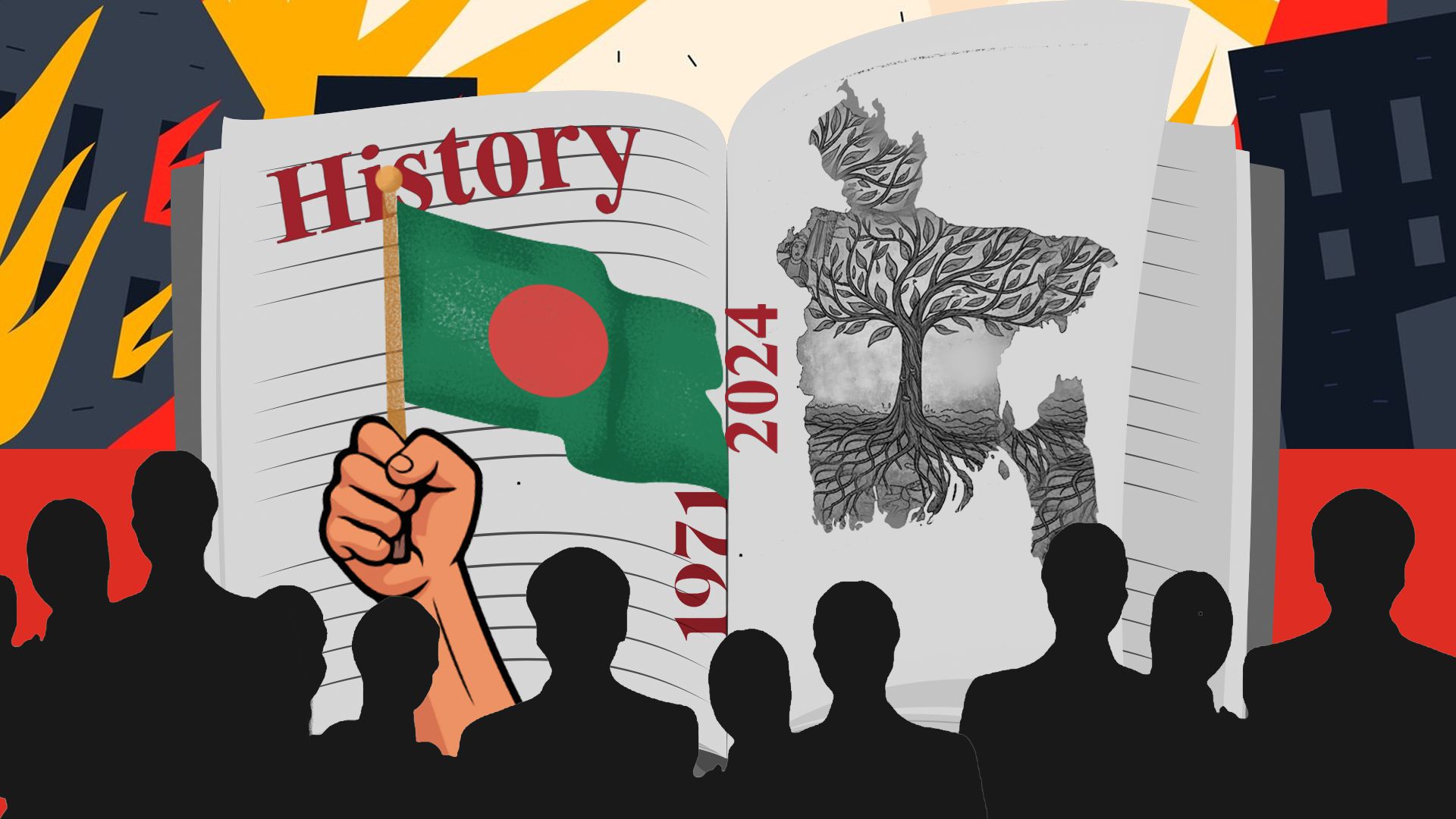

Many Bangladeshi historians and intellectuals have reinforced this habit of seeing ourselves only as victims. The genocide of 1971, the crimes of the Pakistani army and their allies, and international indifference were all real, but we rarely ask with equal seriousness how we built the new state, who gained from it, and who was left out. In 2024, a student-led mass uprising toppled the Sheikh Hasina government, and an interim administration led by Dr Muhammad Yunus took charge, yet public debate quickly slid back to old labels such as "pro-India," "anti-Islam," and "traitor," and to suspicion over who is plotting with whom. Once again, issues of land, wages, education, health, law, and justice moved to the side, as if every change of regime must be reduced to choosing a fresh victim and a fresh villain, while the hard work of state-building remains untouched.

Ordinary citizens share the burden of responsibility as well. When, for instance, thousands of madrasa students are taken to Dhaka to shout for death sentences, they could ask why teachers are suspending class lessons to use them as a crowd; when a schoolteacher takes attendance and then spends the class on their phone, parents and students could question this neglect. Instead, we invariably fall back on blaming some outside conspiracy or influence. My point is simple: "We are oppressed" is not a lie—colonial rule, military rule, and state violence are indeed facts—but as citizens we have also helped, actively or silently, in the continuation of oppression. As long as our histories place all guilt on "the British," "the Hindus," "the Muslims," "India," "Pakistan," or "the West," while hiding the greed of our own elites, our political shortsightedness, and our moral weaknesses, we are dirtying the mirror in which we should be examining ourselves.

We have to do two things at once: clean up our public narratives in which all fault lies with "them," the other, and clean up our own conduct, starting with a frank admission that we are at once victims and makers of our own victimhood. Only then can a real political conversation begin.

Asif Bin Ali is a doctoral fellow at Georgia State University, USA. He can be reached at abinali2@gsu.edu.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments