Party nominations and the systemic exclusion of women

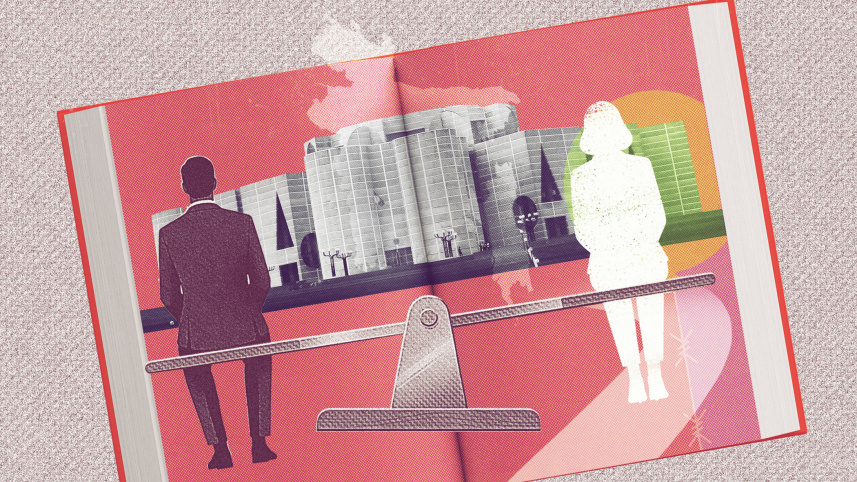

Bangladesh is not unfamiliar with the image of women in power. In fact, two women have governed this country for nearly the entirety of its democratic era. Their names are etched into national history and public memory alike. And yet, when the arena shifts from symbolism to competition, women almost disappear.

In the upcoming parliamentary election, only a small fraction of candidates are women. The figure—just over four percent of all candidates—is not merely disappointing; it is an alarming political diagnosis that sheds light on how power is still organised, circulated, and protected even after a bloody uprising that was supposed to usher in change in our political system.

The lack of women candidates has nothing to do with women’s competence or willingness to lead, but everything to do with systemic design and failure.

The paradox here has become normalised by now: a nation comfortable with women at the helm of authority but consistently unwilling to open the ladders below. Visibility at the top has not translated into proper access at the base. Representation has remained symbolic, while power has remained structurally guarded.

Political theory has long warned us that formal equality can coexist with deep injustice. Iris Marion Young’s work on structural inequality is instructive here. Exclusion, she argued, often operates not through overt discrimination but through systems that appear neutral while reproducing inequality as a matter of routine. When institutions are built around the resources, risks, and norms of a dominant group, others are filtered out without anyone needing to explicitly bar the door.

This is precisely how our politics now functions.

On paper, women are free to contest. In practice, nominations are shaped by patronage, money, informal loyalty networks, and a political culture in which intimidation and risk are not incidental, but embedded. These are not gender-neutral conditions; they privilege those already embedded in male-dominated circuits of influence and capital.

Yes, reserved seats still exist, and they matter, but they have also led to presence without parity, and visibility without fair competition. Too often, they become a substitute for mainstream inclusion rather than a bridge into it. Sadaf Saaz, executive director of Naripokkho, captured this dissonance with precision when she observed that even parties born out of the mass movements, where women played central roles, now treat women’s nominations as peripheral. Jesmin Tuli, a member of the Electoral Reform Commission, was more direct: “Elections are not women-friendly,” she said, noting that major parties nominate very few women while smaller parties simply follow their lead.

When political competition is designed in ways that systematically disadvantage women, low representation is all but inevitable. This matters not only because it is unjust but also because it weakens democracy itself. Representation is not a matter of optics. It shapes whose experiences enter policy debates, whose priorities are discussed, and whose vulnerabilities are addressed. When half the population is structurally excluded from contesting politically, democratic choice becomes thinner, and legitimacy becomes fragile.

We often frame women’s participation as a social development concern, adjacent to “real” politics. That is a mistake. This is actually a governance problem.

And it is neither novel nor complex. Other large, power-holding institutions have already learned this lesson. In many multinational corporations, women’s leadership is no longer left to goodwill; it is structurally and systematically governed. Clear short-, medium-, and long-term targets are set. Internal pipelines are deliberately developed. Mentorship and sponsorship are institutionalised. Strategic external hiring is used to correct imbalance. Progress is reviewed on fixed schedules. When outcomes fall short, strategies are recalibrated. In other words, representation in such a setting is treated as an organisational design challenge, not as an act of benevolence.

Politics, by contrast, continues to treat women’s participation as a gesture, renegotiated before each election and forgotten immediately after. But if institutions responsible for global capital can systemically expand women’s leadership, institutions responsible for democratic legitimacy can do no less. The question is who should do it.

The primary responsibility rests with political parties, of course. They are the true gatekeepers of power. They control nominations, internal hierarchies, access to resources, and political legitimacy at the constituency level. It is within party offices, not polling stations, that exclusion is most efficiently produced. Without structured, time-bound programmes for developing and promoting women’s political careers—through mentorship, leadership roles, financial backing, and transparent selection criteria—rhetoric will continue to substitute for reform, and commitment will remain performative.

The Election Commission’s role in this is as important as that of political parties. Speakers at a recent event have rightly demanded accountability of both political parties and the Election Commission for the former’s failure to honour their pledge in the July National Charter to nominate women for at least five percent of parliamentary seats in the upcoming election. Worse, 30 of the 51 contesting parties have not nominated a single woman candidate, and the EC let it happen without question, consequence, or public explanation. So it is imperative that minimum standards of representation are enforced as a binding electoral requirement.

The parliament, in turn, must reform the legal and financial architecture of elections so that competition is not structurally skewed against women. Campaign finance rules, nomination procedures, and the design of reserved seats and political nomination of women candidates all require careful reconsideration if equality is to be substantive. And civil society and the media must continue to measure, expose, and insist.

Iris Marion Young reminds us that structural injustice cannot be corrected by goodwill alone. Bangladesh’s political history has shown us that symbolic breakthroughs, however important, are not sufficient. The presence of women at the top cannot compensate for exclusion at the base. Until our institutions and party systems are reshaped to redistribute political opportunity, representation will remain procedural and power will remain concentrated.

There is a deeper irony here that our political culture rarely confronts. Bangladesh was born through collective struggle, and much of that struggle was carried, quietly and visibly, by women whose courage and endurance were never fully institutionalised into the power structure. We remember them in stories, in slogans, in anniversaries, but we have never quite learned how to build systems that carry their legacy forward. Our democracy has learned to honour women in memory, but not to accommodate them in formal structure.

The question is no longer whether women can lead. That has been answered, repeatedly. The question is whether our democracy is capable of making room for them, and that is not a women’s issue. It is a test of our democratic maturity.

Tasneem Tayeb is a columnist for The Daily Star. Her X handle is @tasneem_tayeb.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments