A fair chance to learn: Why the future of education depends on digital access

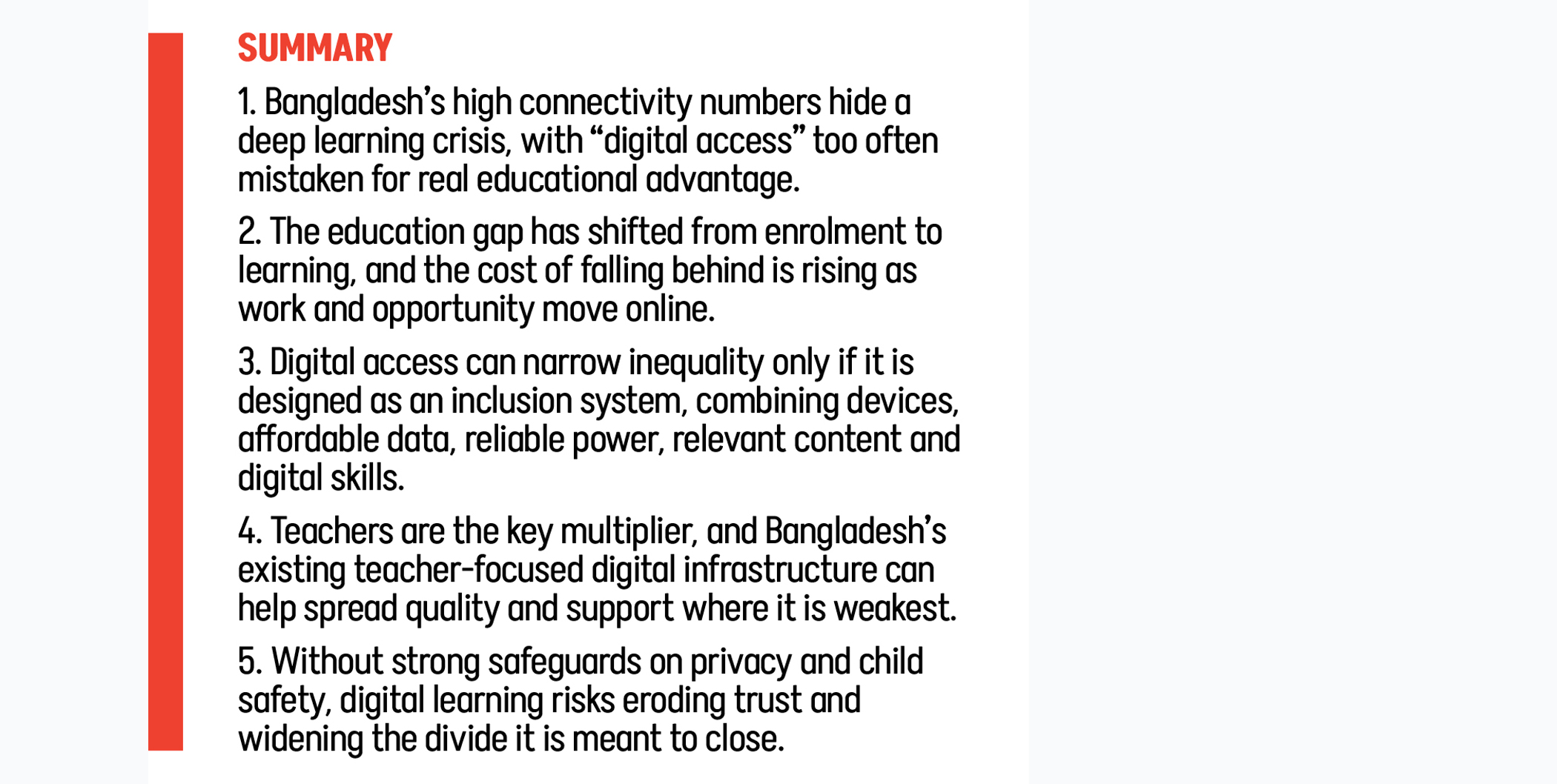

Bangladesh is living through a paradox. On one hand, we are more connected than ever. Official figures from the telecoms regulator show 131.49 million internet subscriptions as of October 2025, including 116.87 million mobile internet subscriptions. On the other hand, connection has not yet translated into equal opportunity. The World Bank’s most recent Learning Poverty brief estimates that 51 percent of children of late primary age in Bangladesh are not proficient in reading, adjusted for out-of-school children.

These two realities coexist because “digital access” is often confused with “digital advantage”. A SIM card is not a classroom. A smartphone is not a teacher. An internet subscription is not the same as meaningful connectivity, especially when a household shares one device among several siblings, electricity is unreliable, or a student must choose between buying data and buying dinner. We should be honest about this, because honesty is where progress begins.

When we talk about narrowing the education gap, we are talking about real children in real places: a girl in a rural village expected to help at home after school; a boy in an urban settlement who has never had a quiet corner to read; a child with a disability whose school was never designed with accessibility in mind; a refugee child whose education can be interrupted overnight by circumstances beyond their control. The education gap is not one gap. It is a web of gaps that reinforce one another.

In one coastal district, a Class 5 student I met shares a single phone with three siblings. Her online class begins at the same time her mother needs the phone for work. She logs in when she can, and hopes the lesson is still there.

Digital access can help cut through that web, faster than traditional systems can expand brick by brick. But it will only narrow the gap if we treat it as an inclusion strategy, not a technology project.

The education gap is shifting, not shrinking

A decade ago, the gap was largely about enrollment. Today, Bangladesh has made important progress in getting children into school, yet the learning crisis remains severe. At the same time, the world is reorganising itself around data, automation and artificial intelligence. The penalty for falling behind is growing.

If a child leaves school without strong literacy, numeracy and digital confidence, they do not just face a tough job market. They face a job market being redesigned around skills they were never given the chance to build.

This is why digital access matters now more than ever. Not because screens are fashionable, but because the future is increasingly screen-mediated. Knowledge, credentials, mentorship, job discovery and professional networks are moving online. If access is unequal, the future will be unequal.

Even headline connectivity numbers can mislead us. Bangladesh’s internet subscription count includes many connections that do not represent distinct individuals. Multiple SIM ownership, often registered under names other than the actual user, remains common. For education, this matters because learning is meant to extend beyond the school day. When connectivity is fragmented, shared or unstable, children experience it as scarcity, not empowerment.

When digital access widens inequality

The pandemic years left us with a lesson we should not forget. When schools closed and learning shifted online, research in Bangladesh showed deep socio-economic and gender-based divides in access to televisions, smartphones, computers and the internet. Crucially, it also found that technology access alone produced only modest learning gains unless other supports were present.

Putting content online is not inclusion. If a child lacks a device, cannot afford data, struggles with the language of instruction, has no quiet space to study, or has no adult to help them navigate learning, digital education becomes another advantage for the already advantaged.

We must design for the learner who has the least.

Meaningful digital access requires several elements to work together: a reliable connection, an appropriate device, affordable usage, relevant content, and the skills and safeguards to use it safely. Remove any one of these, and the promise collapses.

Where digital access genuinely narrows the gap

When meaningful access is in place, the impact can be transformative, and very practical.

A student in a school with limited subject teachers can follow high-quality lessons aligned to the national curriculum, revisit difficult concepts and practise at their own pace. A child who is shy in class can ask questions privately and receive feedback without embarrassment. A first-generation learner can replay explanations until a concept clicks, instead of falling behind forever because the class moved on.

For teachers, digital platforms can act as force multipliers. Bangladesh has already invested in teacher-centred digital ecosystems. UNESCO has highlighted the national Teachers Portal, which now serves more than 600,000 registered educators, enabling them to create and share content and access professional development. This matters because teacher quality is one of the strongest predictors of learning outcomes, and teacher support is often weakest where poverty is highest.

For parents and communities, digital tools can make learning visible. Many low-income parents value education deeply but feel powerless because they cannot help with homework or do not understand the curriculum. Simple, mobile-first guidance in Bangla and plain language can help families support routines, attendance and reading practice. This is not glamorous innovation, but it is the kind that changes trajectories.

New technologies also matter. Across Bangladesh, education platforms are beginning to experiment with AI-based assessment, feedback and personalised tutoring. Used responsibly, these tools can reduce the cost of high-quality practice and coaching, services that wealthier families have always been able to buy privately, while poorer families could not. The right digital models can democratise what was once a privilege.

The real barriers are social and economic

Affordability remains a major constraint. Even where mobile data prices are relatively low, the true cost of learning includes the device, repairs, charging, data top-ups, and the opportunity cost of time spent studying rather than earning.

Gender norms compound the problem. Research on low-income women in Bangladesh shows how limited digital literacy, financial dependence and restrictions on device ownership shape access. When a girl must ask permission to use a phone, or when the “family smartphone” is controlled by male relatives, access becomes conditional. Conditional access does not close gaps. It reproduces them.

Structural barriers persist too: unreliable electricity, unsafe study spaces and uneven content quality. A child can be connected and still learn very little if the content is not engaging, aligned and scaffolded. This is why pandemic-era evidence is so important. Digital learning must be designed as a learning system, not a content dump.

What a serious national approach would look like

If Bangladesh wants digital access to narrow the education gap, a few outcomes should guide us.

Within five years, every public primary school in Bangladesh should meet a minimum digital learning standard: reliable electricity, basic connectivity, shared student devices, and offline-capable national curriculum content.

Every teacher should receive ongoing digital pedagogical support, not one-off training. The existing teacher portal ecosystem is a strong foundation, but the next step is helping teachers integrate digital tools into lesson planning, assessment and remediation in ways that make classrooms more inclusive rather than more complicated.

Every learner should have access to low-bandwidth, offline-capable content. Designing offline-first is not a technical detail; it is a statement of who we prioritise. When offline functionality is treated as a core requirement, students in hard-to-reach areas stop being an afterthought.

Every young person should also see a clear pathway from school learning to employable skills. This is where Bangladesh’s startup and edtech ecosystem can contribute, by building affordable, outcome-driven products that bridge school curricula and the future of work, including the skill shifts driven by AI.

Trust, privacy, and child safety are non-negotiable

Digital learning environments collect data, shape behaviour and can expose children to harm if governance is weak. If families lose trust, the very communities we aim to reach will disengage.

Bangladesh is moving toward data protection legislation, but the debate highlights the need for stronger safeguards and independent oversight. In education, this is especially sensitive. Children are not consumers; they are rights-holders.

Any digital learning programme, public or private, must minimise data collection, secure it properly, be transparent about how data is used, and never condition access to learning on the surrender of privacy. Strong governance is not a barrier to innovation. It is the foundation for responsible scale.

Image: Esma Melike Sezer/ Unsplash

The opportunity before us

Bangladesh’s education system serves more than 40 million students and employs nearly one million teachers. The scale is daunting, but it is also our strength. When Bangladesh commits, we can move fast.

Digital access will shape who learns, who earns and who belongs in the next Bangladesh. If we get it right, technology becomes a ladder: portable, scalable and fair. If we get it wrong, it becomes a wall, invisible but permanent.

The choice is not about devices or platforms. It is about whether we believe every child deserves a fair chance to learn, no matter where they are born. Bangladesh has made harder choices before. This is one we must make now.

Korvi Rakshand Dhrubo is the founder and CEO of Jaago Foundation, a non-profit organisation in Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments