‘Ekhane Rajnoitik Alap Joruri’: Ambitious, flawed, hopeful

At Bangladesh’s tea-stalls, on public transport, or inside religious entities, one often sees a notice hung like a commandment: “Political discussion is prohibited here”. But the very idea of prohibiting political discussion, usually born from a personal desire to remain safely distant from political trouble, is itself a political act.

At the end of the day, politics is inseparable from human life; every individual is a political being, and it is from this very premise that the film “Ekhane Rajnoitik Alap Joruri” emerges.

Directed by musician-turned-filmmaker Ahmed Hasan Sunny, this debut feature film was released in theatres on January 16. The film is led by Imtiaz Barshon, who plays the lead character Nur, and Tanvir Apurbo, who plays his younger brother Mukto.

Nur, a Bangladeshi professional living in the Netherlands, has returned home on vacation and will leave again in a few days. Before that, he sets out for Kuakata.

On a vast island near Kuakata, where Nur’s younger brother Mukto—who was killed in the July uprising—had once planned to shoot the ending scene of his documentary. Along the way, he encounters Azad, a forest officer, who, during their bus journey, begins sharing his personal interpretations of the anti-British movement and the Partition.

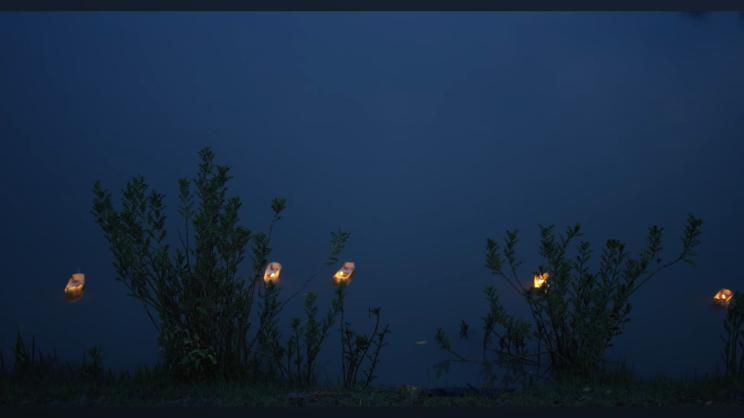

From there, through a turn of circumstances, Nur finds shelter in the home of Satya Das, an educated fisherman. On a gloomy coastal night, Nur listens as Satya and the coincidentally present Azad narrate stories of Bangladesh’s emergence and its subsequent political turmoils.

Through this, the political continuity of the state called Bangladesh, up to 2024, gradually unfolds.

This continuity reveals a new path to Nur—a path that teaches how essential it is for a person, as a citizen, to become politically concerned.

Written by Khalid Mahbub Turjo, Motasim Billah Aditya, and Ahmed Hasan Sunny, the political intensity of this story is commendable. We experience the entire narrative from the position of a spectator, as Nur, the central character, voraciously consumes one political wave after another from the Bengali region.

If the screenplay is to be summarised briefly, it can only be described as confused and monotonous.

A large portion of the first half is largely linear one-on-one conversations. While recounting the history of the Partition, Azad presents it primarily as a conflict between Nehru and Jinnah, despite it being widely established that Partition was a historical inevitability of its time. In that context, the British policy of divide and rule finds no reflection here.

Rather than unpacking the layered realities of history, the screenplay presents a linear lecture.

Explaining the Partition through the statement, “Economics is a policy that reshapes politics itself,” feels inadequate. It is true that Kolkata’s elite Bengalis did not wish to be part of this land, just as it is true that had Bengal remained united, the binary question of Kolkata or Dhaka would inevitably have arisen, but none of this appears in the story.

The notion that Pakistanis viewed Bangladeshis as lower-caste Muslims is introduced anew in this film.

Yet the deeper reality that Pakistani oppression stemmed more from nationalist tensions born out of the language movement—a crisis Pakistan still grapples with—remains absent.

However, the most interesting and positive aspect of this screenplay lies in its depiction of major historical events and the journeys of institutions formed around them, such as the Purbo Bangla Rashtrobhasha Songram Parishad.

Although historical figures are largely absent, anyone would gain a broad understanding of the struggle’s history. In the following conversation with Satya Das, political leaders receive greater emphasis than events themselves. Leaders from the period surrounding 1971 dominate this exchange.

The Golahat genocide is mentioned, but the Liberation War—a monumental chapter—is narrowly framed through the binary of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Maulana Bhashani. Frequently, Satya concludes his historical accounts by labelling them as “hearsay.” Despite the film being titled “Political Discussion is Necessary Here,” a line dismisses the importance of asking what India sought during the Liberation War as though it were not a political question.

General Zia is portrayed as a just ruler, while another military dictator, Ershad, is cast as a villain, with the justification again resting on hearsay. Yet, within cinematic language, hearsay itself becomes a narrative foundation. As mentioned earlier, the first half is painfully slow, laden with theoretical dialogue, sustained entirely by conversations without which the film could still have progressed.

This nearly hour-long half merely revisits familiar history, adding no new substance. The latter half, however, which addresses the July movement—its context, representation, and synthesis of perspectives—deserves praise.

Portraying the July uprising through the viewpoints of two different individuals effectively reflects its socio-economic reality. Although the misrepresentation of private university students, the absence of women’s roles, the lack of a clear July timeline, and major plot holes—such as news of Abu Sayed’s funeral appearing on the same day as the Shaheed Minar gathering—will unsettle anyone involved with the uprising, this segment still manages to move the story forward meaningfully.

These errors, however, remind us that our filmmakers themselves need to engage in far more Rajnoitik Alap themselves.

The most compelling element of the film lies in the public opinions recorded for Mukto’s documentary.

Highlighting how enforced disappearances paralyse independent journalism, and how citizens freeze when asked about democracy, marks Ahmed Hasan Sunny’s strength as an activist filmmaker.

Imtiaz Barshon blends smoothly into the role of Nur, fully commanding his screen time.

In this film, Nur is a traveller, his journey unfolding across political roads, historical roads, and the enduring cultural landscape of Bangladesh. Barshon delivers a natural performance in this regard.

The generation Nur represents is more accustomed to questioning facts and engaging through denial than merely listening. We do not see Nur in such moments.

Whether listening to Azad or Satya, he rarely questions the history being constructed before him, despite the film advocating political discussions.

Manoshi, played by Keya Al Jannah, is not given a powerful presence.

Her screen time is limited, though she does her best within it.

In fact, the film scarcely contains female characters at all—much like the token presence of women candidates in upcoming parliamentary elections, or the erasure of women from the July movement.

Satya Das, an educated fisherman nearing the end of his lived journey, adopts a revolutionary stance.

Azad Abul Kalam portrays this role. Poor dialogue delivery, coupled with confusion over linguistic register—whether colloquial or regional—renders him stiff. Ironically, the agricultural movement itself emerges as a stronger character than Satya.

A K Azad Setu’s performance as forest officer Azad offers little room to shine; the dialogue outweighs the character.

Tanvir Apurbo’s portrayal of Mukto really stands out.

He utilises his limited space effectively, owning the character through subtle eye movements and precise dialogue delivery.

The film’s cinematography is visually pleasing.

Abu Raihan’s camera captures expansive forests and oceans via drone shots, twilight framings, and conversations from varied angles. Nur running alone across waves and green plains, and the final crane shot at Shahid Minar, feel appropriate. Master shots that give space to each character are commendable.

However, focus issues in B-roll footage and lighting inconsistencies undermine several shots. Indoor lighting is aesthetically pleasing, but outdoor lighting suffers greatly. Inconsistent natural light disrupts scene continuity; cloudy skies abruptly cut to sunlit shots, and lighting discrepancies before and after disembarking boats are glaring.

The film’s editing feels disjointed. Extensive July stock footage is used, but its brief duration fails to convey context, creating fragmentation with principal footage. Chronology is also broken, such as cutting from an evening grave visit to a daytime protest scene.

These errors weaken the film’s merit.

Yet documentary-style presentations and protest sequences reveal notable editorial skill, particularly in nighttime island conversations. Colorist Jahir Rayhan employs a dark, gritty, high-contrast palette—an experimental choice that surprisingly works well on the big screen.

Music direction by Ruslan Rehman and background score by Abhishek Bhattacharjee are powerful.

The score builds suspense, introduces melancholy, and experiments effectively. The song “Amay Emon Dukkho Debe Jodi,” sung by Ahmed Hasan Sunny, is beautiful, though poorly blended into the film.

The overall sound design is solid, with balanced echo throughout. However, Foley inconsistencies—sudden animal calls or ocean roars intruding upon dialogue—feel awkward, despite contextual setups.

The protest sequences, however, feature excellent sound design.

Most technical flaws and narrative monotony reside in the first half, which attempts to educate audiences on regional political history but only captures fragments of the whole.

Thus, while the film qualifies as political cinema, it cannot be considered a political historical reference.

The second half could have existed independently as a story, though doing so might have weakened the director’s attempt to weave 1947–71–90–2024 together.

That ambition itself deserves appreciation.

Most importantly, the film urges us to reconsider our political consciousness. It repositions us before the history of our struggles and reminds us that Bangladeshis took to the streets in July 2024 as part of a historical continuum, and that taking to the streets is itself a political act.

This act offers new hope—a hope strong enough for a Dutch expatriate like Nur to choose staying back home. Amidst the many criticisms of the “capture” of July by different vested groups, hope is exactly what we need at this point.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments