Through fragments, Tadattwo Onneshan pieces together the forgotten

History traces grand narratives. The occurrences it speaks of and studies continue to transcend time not simply because of their magnitude, but because they’re made profound by personal, more intimate tales. What is remembered are not just the things that were altered but also what was lost. And so, the act of unearthing lineage becomes more than an act of observation. It evolves into an arduous task, one that demands introspection of the self, not through our lived experiences, but rather by forgotten tales.

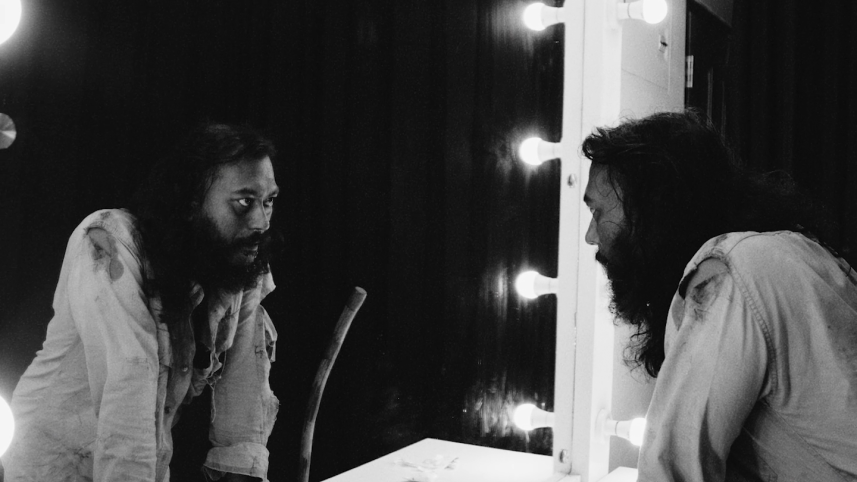

Tadattwo Onneshan (2025) by Fozle Rabby contemplates what one can truly stumble upon when they devote themselves to this task. The experimental short clocks in at a 16-and-a-half-minute runtime. Despite its short length, the film is deeply meditative, oscillating in-and-out of the protagonist’s psyche and material world. It follows Pankaj Chowdhury – a theatre actor – as he prepares for the role of Kute Kahar, who is a member of a palanquin bearer community, known as Kahar.

As the film unravels, its surreal quality – present through strobing and distorted visuals, as well as sporadic high-pitched soundscapes – flutters. Yet, the progression is patient, carefully weaving out the descent to run parallelly with the performer’s state of mind. In the initial stages of his preparation, Pankaj clings onto the enunciation of the word ‘forgot’. He repeatedly questions a consultant from Kute Kahar’s region, persistent in his attempt to perfect it. Within minutes, however, Pankaj is reciting entire lines. Fully enveloped, he adopts a gruffness to his vocal delivery that is chilling.

The horror takes on a new form when Pankaj’s performance adopts the physical aspect. He is hunched over, gazing directly at the audience, stripping himself bare, and even carrying stacks of bricks as if to permanently alter his posture. The performance by the protagonist is not an easy watch, and it isn’t meant to be either. We are confronted by the full weight of his devotion to becoming Kute Kahar, no matter the cost. The intention with which his desire is portrayed feels evocative. The film doesn’t give in to the banal conveniences that passionate artists on-screen are often characterised by. Rather, it draws from the absurdity.

With Pankaj’s growing vehemence, he literally hurls himself into nature. This is perhaps when the film’s strongest attribute, its cinematography, really shines through. The performer is seen lying by the river, huddled deep within the forest, and wedged between broken tree barks. These images are haunting and unsettling in more ways than one, owing to their unorthodox composition, tactile feel, and sharp contrast.

Coupled with the cinematography are repetitive lines that gradually arrive at its conclusion. The limited dialogue alludes to the forsaken memory of Kute Kahar. With each new line, it feels as though the performer — who has been entirely inundated by the role — is clutching onto whatever he has been allowed to know of Kute Kahar. Despite the repetition, the soliloquy doesn’t feel drawn out. Rather, it reveals points of contention, withering hope, and perhaps even contempt.

The film stands out for its technical mastery. In each turn, it is deliberate without being contrived and intentional without being overbearing. More than anything, Tadattwo Onneshan hints at a powerful reminder, particularly of history. It feels as though the film is asking the audience to consider where precisely the history of the common folk lies. Have they been left to wither against the backdrop of our advances? Is there a place for us to remember them? It is these questions that the film confronts us with and even attempts to decipher through the devotion of a stage performer.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments