Two forgotten kingdoms of Bengal

Maps are regarded as affirmative visual documents, permanently fixing places, distances, and itineraries in our minds. Yet we often forget that early modern maps were subjective texts, only approximating places. Moreover, European mapmakers frequently chose to assign names to locations that bore little relation to their actual identities or physical positions. This essay examines two such cases in Bengal: the kingdoms of Chandecan and Codovascam, located in what were once Samatata and Harikela.

I

Pratapaditya Roy (b. 1561 – d. 1611–12) envisioned a maritime polity that held together the port-based kingdom known as the Regno de Chandecan. Initially, Pratapaditya ruled the landlocked territory of Jessore, establishing his capital at Dhumghat — a strategic point at the confluence of the Jamuna (Brahmaputra) and Ichhamati rivers. The capital was later shifted south to Ishwaripur, also known as Jashoreshwaripur, on the Ichhamati in Khulna, with direct access to the Bay of Bengal. This site became the capital of the chiefdom from 1590 to 1612, featuring extensive shipyards and dockyards at Jahajghata or Khanpur, and also at Dadkhah and Chakvasi.

This was a maritime chiefdom, benefitting from the eastward shift of rivers that endowed the southeastern delta with new military outposts and strategic locations for trade. Pratapaditya built the Jashoreshwari Kali Temple at Ishwaripur, perhaps as a commemorative act — though of what we do not know — and the Jashoreshwari Kali appears to have become the polity's tutelary deity. Despite this, Chandecan remained an open, pluralistic kingdom. The Portuguese built Bengal's first Catholic church in Ishwaripur in 1599–1600 with funds provided by Pratapaditya.

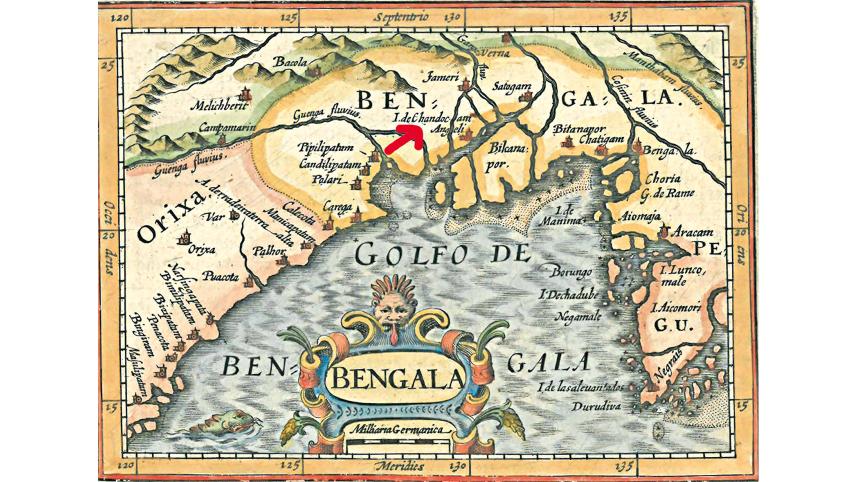

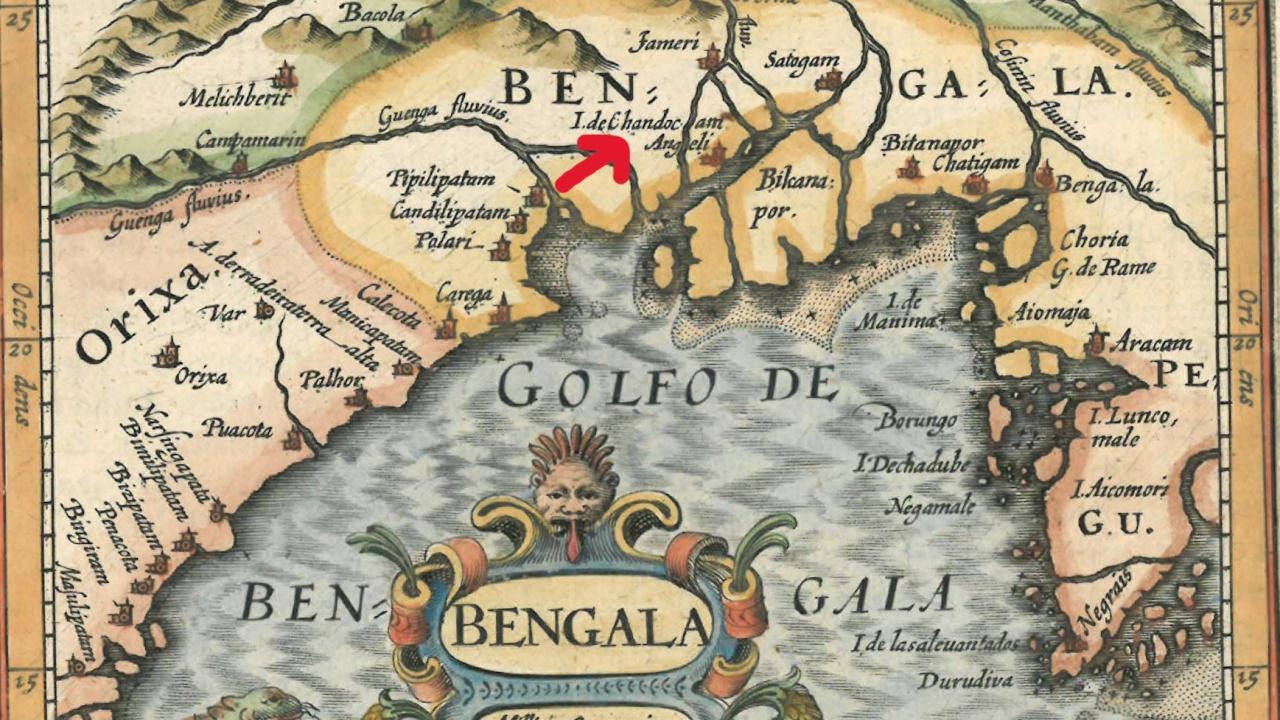

Chandecan's prominence in the early seventeenth century is attested to by contemporary cartography. Bertius' Map of Bengal (1600) marks the delta as Isola do Chandocam, reflecting the chiefdom's maritime character. However, in Dudley's hydrographic map of the Bengal coast, dated 1646, the island transforms into the Regno di Chandican.

This transition from island to kingdom indicates Chandecan's changing political fortunes. The territory originally ruled by Pratapaditya was too small to constitute a kingdom. His family held a small chiefdom; it would be anachronistic to describe it as a zamindari, as the term implies a British-era classification of property ownership in eighteenth-century Bengal.

So, what — or who — was Chandecan? The term Chandecan was a Portuguese corruption of "Chand Khan". Daud Khan Karrani, the last independent Sultan of Bengal, had granted Pratapaditya's father, Srihari (or Sridhar) — an influential officer in his service — the title of "Vikramaditya" and the lands of one Chand Khan, who had died intestate. Following Daud Khan's fall in 1576, Srihari took advantage of the turmoil caused by the Mughal conquest of western Bengal to declare independence, assume the title of "Maharaja", and lay the foundations of a chiefdom spanning West Bengal and southeastern Bangladesh.

Between 1598 and 1609, the kingdom of Chandecan — originally encompassing the deltaic outlet of Bakla (Chandradwip, the Chandra port of ninth–tenth-century Bengal, later Bakargunj in Barisal) — extended its control over the port of Sagor (south of Kolkata) and the island of Dakhin Shabazpur (in the southeastern delta), as well as, for a time, the ports of Sripur (south of Dhaka) and Sandwip (opposite Chittagong). The kingdom stretched from Jessore and Khulna in the north to the Sundarbans and the Bay of Bengal in the south, Barisal in the east, and the Ganga in the west — encompassing most of the present-day districts of Jessore, Khulna, and Barisal. Its governance combined direct control (over Sagor and Bakla) and indirect authority (Pratapaditya claimed revenues from Sripur in 1608 and Sandwip in 1609).

What lay behind the remarkable expansion of this chiefdom? Through a system of strategic alliances and warfare amid a period of rapid political flux, Pratapaditya succeeded in carving out a short-lived but dynamic maritime kingdom. He adopted, consciously or otherwise, the Portuguese model of controlling strategic posts along the Indian Ocean. The economic dislocation caused by the shifting alignment of diverse overland and maritime networks — Sultani, Afghan, Mughal, Arab, Persian, Tripuri, Arakanese, and Portuguese — in fact enabled his royal ambitions.

Pratapaditya was the father-in-law of Bakla's ruler, Ramchandra, son of Kandarpanarayan Rai, a baro bhuinya who reigned from 1584 to 1598. Ramchandra married Pratapaditya's daughter Bindumati and established his capital at Husainpur. Bakla, a profitable port, was thus left free for Pratapaditya to occupy after 1598. Earlier, on April 30, 1559, a treaty had been signed at Goa between Paramananda Rai, then ruler of Bakla, and the Portuguese Viceroy Constantino de Braganza, by which Bakla was opened to Portuguese shipping under fixed and low customs duties. In return, Bakla received a licence for four ships to trade with Goa, Hormuz, and Melaka. This Hormuz–Goa–Melaka route, extended by stops at Bakla, Sripur, and Sandwip, established a new Portuguese network in southeastern Bengal — a legacy Pratapaditya inherited through his daughter's marriage to Paramananda's grandson. With Bakla secured, Pratapaditya embarked on a campaign of coastal expansion, the first obstacle to which were the Portuguese themselves.

Pratapaditya dealt with the issue of Portuguese expansion through a system of shifting alliances. Around 1600, while holding court at Bakla, he granted the Jesuit Father Fonseca permission to erect churches and carry out conversions. At the same time, Pratapaditya sought to wrest control of Sandwip from the Portuguese in alliance with Arakan by beheading Carvalho, its unofficial ruler, in 1602. Yet by 1609, he supported the Portuguese Gonçalves at Sandwip against both the Mughals and Sripur, under whose jurisdiction Sandwip fell. The Afghan adventurer Fateh Khan, in Portuguese pay and notorious for his shifting loyalties between the Mughals and Arakan, then controlled Sandwip. Gonçalves, trading through Pratapaditya's ports, defeated Fateh Khan's forces in alliance with Pratapaditya. In return, Pratapaditya claimed half of Sandwip's revenues, but Gonçalves turned against him and seized the island of Dakhin Shabazpur, which lay within Pratapaditya's domains.

Early seventeenth-century delta politics must be viewed against the backdrop of these rapid changes. After Sripur's Kedar Rai died, Pratapaditya attempted to take over Sripur, but it fell under the control of Isa Khan's son, Musa Khan, ruler of Sonargaon. Musa governed Dhaka, Sonargaon, almost half of Tripura, Mymensingh, Rangpur, and parts of Bogura and Pabna. As Chandecan expanded, its borders approached Musa's territories, explaining Pratapaditya's reluctance to aid the Mughals against him.

Among the delta chiefs, Pratapaditya was the first to send his envoy to the Mughal subahdar Islam Khan Chishti with a lavish gift to secure imperial favour, before personally submitting to him in 1609. Pratapaditya agreed to surrender twenty thousand infantry, five hundred war boats, and a thousand maunds (approximately 41 tons) of gunpowder — an exceedingly expensive commodity at the time. He also pledged military support and personal service in the Mughal campaign against Musa.

This, however, was a promise Pratapaditya did not keep.

To punish him for his disloyalty, a Mughal expedition under Ghiyas Khan's command advanced to Salka, near the confluence of the Jamuna and Ichhamati, in 1611. Pratapaditya assembled a strong army and fleet, and built a supposedly impregnable fort, placing it under the command of experienced officers, including feringis (Portuguese), Afghans, and Pathans. The Mughals, however, cut off the Jessore fleet, forcing the fort's evacuation. Pratapaditya prepared for another confrontation from a new base near the junction of the Kagarghat canal and the Jamuna. He built another fort at a strategic location and concentrated all his remaining forces there. The Mughals launched their assault in January 1612, first attacking the Jessore fleet and compelling it to take shelter beneath the fort. After defeating the fleet, they assaulted the fort itself, forcing Pratapaditya to retreat once again.

This marked the end for Pratapaditya. At Kagarghat, he surrendered to Ghiyas Khan, who personally escorted him to Islam Khan in Dhaka. Pratapaditya was shackled and imprisoned in Dhaka. His kingdom was annexed in 1612.

II

By contrast, far less is known about Codovascam. It was an upstream polity based around the riverine port of Chakoria, located in the remote eastern region of Harikela — a borderland adjacent to Chittagong.

To understand Codovascam's location, one must examine both Chittagong city and its wider district. Chittagong underwent a form of "cartographic surgery" when the United States' post–World War II Area Studies programme divided the region, imposing national and administrative boundaries that bore little relation to Chittagong's once expansive hinterland. The city itself was historically an autonomous border-town and port on a fluid and dynamic water frontier. Its site is distinctive — a complex land–river–sea ecosystem with unstable coastal islands (chars) separated from the mainland by shallow channels and mangroves. To the south, where Arakan and Bengal overlapped, rises the Arakan Yoma barrier. To the northwest, vast waterbodies (haor in the local dialect, derived from the Sanskrit sagar or sagaranupa) extend the Meghna–Brahmaputra waterway into what may be called an "Eastern Sea".

Pratapaditya succeeded in carving out a short-lived but dynamic maritime kingdom. He adopted, consciously or otherwise, the Portuguese model of controlling strategic posts along the Indian Ocean. The economic dislocation caused by the shifting alignment of diverse overland and maritime networks — Sultani, Afghan, Mughal, Arab, Persian, Tripuri, Arakanese, and Portuguese — in fact enabled his royal ambitions.

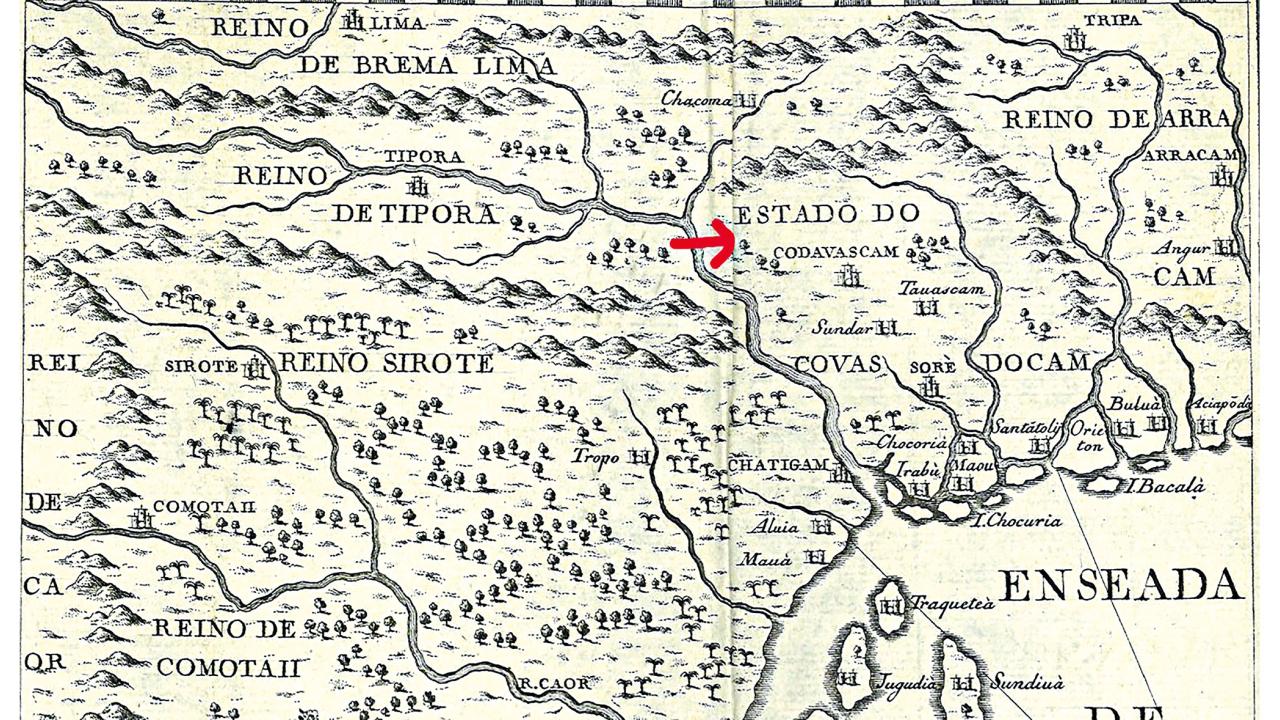

Chittagong district includes the area lying east of the Karnaphuli, whose lower reaches are enclosed by the Kutubdia and Maheshkhali channels extending inland, in addition to the better-known Karnaphuli passage prioritised in historical narratives. This borderland area, corresponding to present-day Cox's Bazar district, was represented on maps as a polity called Codovascam (image 2). The Regno de Codovascam likely corresponded to the territory of Khuda Baksh Khan, a quasi-autonomous Husainid chief who became a Mughal feudatory of southern Chittagong after the region's re-capture from Arakan. Its centre was Chakoria — or Cukkara — a key salt-trading port on the Matamuhuri River, which had been plundered by Arakan King Min Khayi in 1439, consolidating Arakanese control until that time.

Why was Codovascam significant? Like its political environment, this borderland was physically unstable yet potentially lucrative. As Maheshkhali Island rose from the sea, it became Codovascam's maritime gateway, while Chakoria grew into a port of regional prominence. The island originated from a cyclone and tidal bore in 1559, which separated it from Chittagong by the Maheshkhali Channel. Cesare Federici (August 1569) and Ralph Fitch (March 1588) both recorded devastating cyclones in the area. Seismic disturbances also shook this part of the coast. The Ottoman navigational treatise Muhit (1554) speaks of extensive level changes and refers to navigational hazards among islands that have since vanished.

In 1528, Khuda Baksh imprisoned at Chakoria Martim Afonso de Melo Jusarte, a shipwrecked Portuguese captain whose mission appears to have been to open up the Patani–Bengal trade. The event, though seemingly insignificant in the larger scheme of things, became sensational in Europe because de Melo Jusarte was an important officer stationed at Portuguese Melaka, who had led armadas and missions against Pahang and Patani in Southeast Asia.

Mapmakers Blaeu (1606, 1638, Magni Mogolis Imperium, 1659); Barros (1615); Sanson (1648); Jansson (1650 and 1659); de Wit (1662); Valentyn (1724); and Bellin (1747) depicted Codovascam as a fortified city with a maritime outlet. Jansson's Sinus Gangeticus Vulgo Golfo de Bengala, Nova Descriptio (Atlas Atlantis Majoris, 1650) represented it as a coastal power between Chittagong and Arakan, enclosed by the Karnaphuli and Cosmin rivers (the latter being, in fact, the Meghna, since Jansson shows Sonargaon on its banks; moreover, the Cosmin lay further east), and fortified at Dianga, Santatoly, Chorcordia (Choria, Chakoria, Cukkara), Sora, Sunder, Tanascam, and Aciapoda.

However, map depictions changed as the polity's power waned. Van der Aa (1708) shows a diminutive Codovascam lying between the Martaban and Cosmin rivers. Valentyn and Bellin depicted a single fortified town—Codovascam—following the prevailing convention of naming a capital after the region and ruler. Yet Bellin shifted Codovascam's territorial extent westward from Blaeu's and Jansson's locations, bringing it closer to southeast Bengal, between the 'Riviere de Boom' (Bamni, Meghna's eastern branch) and the 'Riviere de Chatighan' (Karnaphuli). It now had Tripura to the north and Bhulua to the south. Evidently, mapmakers struggled to represent Codovascam accurately as it oscillated between contending powers, though it seems to have remained networked with Chittagong. 'Choria' was shown as part of Arakan (Bertius, 1602; Blaeu, 1606; Ramusio–Gastaldi Terza Ostro Tavola, 1603/13; Portuguese Taboas Geraes de toda a navegacao, divididas e emendadas por Dom Ieronimo de Attayede etc., 1630; Jansson, 1650; Van der Aa, 1708).

III

I began by saying that maps are not neutral texts. But I had two other points to make. Chandecan's case illustrated how polities with strategic ports contributed to regional expansion, yet its curious history also demonstrated the short-lived and fragile nature of such minor kingdoms. By contrast, Codovascam revealed a distant past and its transformations within a specific borderland context. Its micro-history exposed differential temporalities — of central importance in exploring the economic, cultural, and social intersections where systems meet or collide.

Since particular sites of micro-historical inquiry act as fragments through which universal processes can be discerned — in this instance, Portuguese expansion in the upper Bay — Codovascam's case offers a means to engage with the chaos, disorder, ruptures, and discontinuities that micro-frames introduce, thereby allowing us to connect the particular with the universal.

Rila Mukherjee is a historian and author of India and the Indian Ocean World (Springer, 2022).

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments