Remembering Munier Bhai

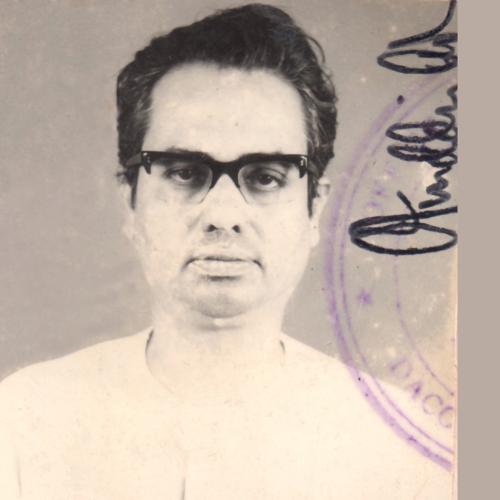

Munier Chowdhury was, in many ways, a highly accomplished man. He was a teacher, a playwright, and an excellent public speaker. He could write beautifully as well. I knew him in two capacities—first as my teacher, and later as a colleague.

As a teacher, what was extraordinary about Munier Chowdhury was that he wasn't just a teacher to us—we used to call him bhai. We couldn't call any other teacher bhai, only Munier Chowdhury. The reason for this came from his own personality—he was extremely charismatic, sympathetic, and responsive. He was affectionate towards us, would call us close, and treat us with great warmth.

We did not have him as our teacher for long, because he eventually transferred from the English Department to the Bangla Department. Before that, in his early life, he had been involved with the Communist Party and had once been imprisoned for a short time in the 1950s. Later, during the 1952 Language Movement, he was arrested again.

During that period in prison, Munier Chowdhury did two remarkable things. First, he wrote the play Kobor inside the jail. It was performed by political prisoners under hurricane lamps in commemoration of the Language Movement martyrs. Second, he sat for his Bangla examinations while in prison and achieved very good results.

When he was released from prison in 1954, we were preparing for our Honours exams in 1955. He joined our English Department for a short time as an English teacher and taught us briefly before moving permanently to the Bangla Department.

Even in that short time, we, his students, were deeply impressed by him. He was remarkable not only in his ability to analyse a text but also in his presentation skills. He had an extraordinary rhetorical quality, was an excellent orator, and carried a wonderful sense of humour—one that ran quietly through all his work. It was never overbearing, but subtle, almost silent, yet always present beneath the surface.

During that period in prison, Munier Chowdhury did two remarkable things. First, he wrote the play Kobor inside the jail. It was performed by political prisoners under hurricane lamps in commemoration of the Language Movement martyrs. Second, he sat for his Bangla examinations while in prison and achieved very good results.

In his writing style, in his speeches, and in his behaviour, there was always a certain sense of enjoyment—as though he truly enjoyed life and had no complaints about it.

If I were to explain how I first came to know him, it would be like this: in 1950, when I was in Class 10, there was an anniversary programme at Curzon Hall marking the death anniversary of the poet Iqbal. I went there out of curiosity—we lived nearby and often wandered around that area—wanting to see what kind of speeches would be delivered.

There, Munier Chowdhury gave a speech on Iqbal's socialist ideas. The way he beautifully presented the socialist concepts embedded in Iqbal's works was remarkable. Whether he took the quotations directly from the Urdu texts or from English translations, he delivered the entire lecture in English.

When the event ended and he was leaving—he used to travel around on a bicycle—many people followed behind him, chatting with him. I too was walking behind. At one point, he said something that still rings in my ears. He told us that Dr W. H. Sadani, a professor of Urdu, had jokingly remarked to him, "I think you could turn Iqbal into a communist." To which Munier Chowdhury replied, "Yes, I certainly could!"

You see, Iqbal held strong socialist ideas while also remaining a believer in religion, as Munier Chowdhury observed. He wrote about social transformation, equality of rights, and themes that echoed various principles of Leninism. It was this intersection in Iqbal's thought that Munier Chowdhury chose to explore in his speech that day.

In that same year, 1950, the first art exhibition by the Art Group was held in Dhaka—at the time, it was not yet an institute but just the School of Art. They organised this exhibition at Liton Hall—part of Shahidullah Hall at Dhaka University.

I went to see it because we were curious about cultural events. I was in Class 9 or 10 at the time. Later, I heard Munier Chowdhury deliver a radio talk about the exhibition. The way he explained the paintings was so vivid and beautiful—I had seen those paintings myself—that it inspired me. Even at that young age, though I hardly understood everything, I wrote an article about the exhibition.

He was very enthusiastic about drama. He himself wrote plays—such as Roktakto Prantor—and he also translated works. For example, there's a short play by Bernard Shaw, You Never Can Tell; he translated it beautifully under the title Keu Kichhu Bolte Pare Na. He even acted in plays. That's why he had a very close relationship with the students.

One thing he always told me was that he found it easier to write if there was a challenge. In drama, there's always a conflict, and just like that, in his own writings, there was always a dramatic quality. He wrote by taking up challenges.

From that perspective, something happened: in 1956, we graduated, and by 1957, I became a lecturer. Towards the end of 1957, our English Department organised a seminar titled "The Capacity of the Bengali Language for Economic and Political Questions" or something similar. Someone had claimed that the Bengali language was incapable of this. He took it as a challenge and gave an extraordinary speech—in English—on the subject. That dramatic sense of challenge was always in him.

Meanwhile, since he had once been accused of being a communist, and because the Americans at that time had a new policy of giving scholarships to highly talented people—especially those with slightly anti-American leanings—he was taken to the USA on scholarship.

Although Munier Chowdhury was from Bengali and English literature, what he studied in America was something new—linguistics. The subject had first been introduced here by Professor Abdul Hai, who had gone to the London School of Oriental Studies to study phonetics. Munier Chowdhury, however, studied not phonetics but linguistics.

Even though he gained knowledge in linguistics, he didn't actually teach it—he taught literature. And in teaching literature, what he did was comparative study. This comparative approach was reflected in his writings and in our study seminars.

Later, during Ayub Khan's regime, there were several bureaucratic people close to him who were also writers—such as Secretary Kudratullah, a major Urdu literary figure. Under his interest and advice, Ayub Khan formed the All Pakistan Writers' Guild, with East Pakistan and West Pakistan regions and a central body connecting writers from both sides.

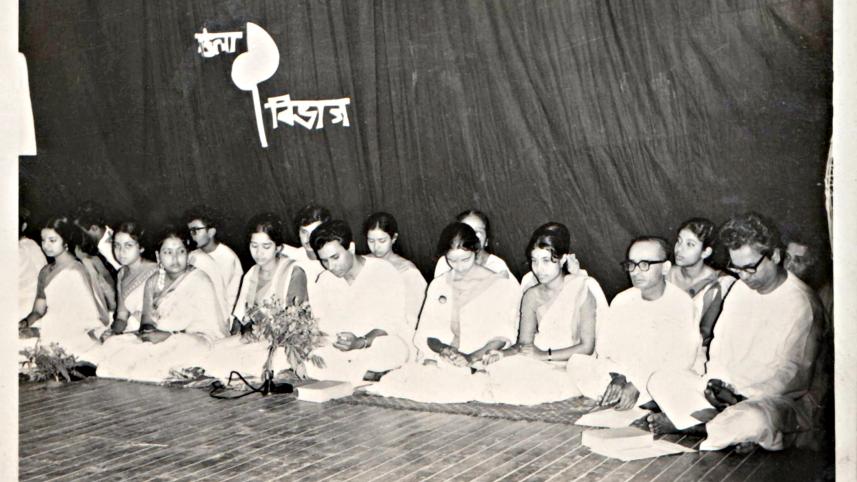

We, as young writers at the time, thought: well, this is a government initiative funded by government money, and since we work at the university—which is also funded by the government—why shouldn't we try to take part in this? So, we contested the election, with Munier Chowdhury as our head. He became the Secretary, and we became members.

We launched a new magazine, which we ran for about one and a half years before I left for England. Even after I left, it continued for a while, though not as before.

We named the magazine Porikroma. I was its editor for the English section, and Rafiqul Islam was the editor for the Bengali section. Both of us were elected.

This magazine mainly published book reviews. In it, we serialised translations of plays by Munier Chowdhury. One of them was Mukhora Romoni Boshikoron, the Bengali translation of The Taming of the Shrew by Shakespeare. We published it over several months, and it was later shown on television, becoming a great success.

On the occasion of a Writers' Guild meeting, we once went to Lahore for a conference. So, in Lahore, we stayed in the same hotel room, a spacious college building. One morning, I woke up and saw him writing. I asked, "Munier Bhai, what are you writing so early in the morning?" He said, "Well, I'll have to speak extempore there, so I'm preparing by writing it down." That was Munier Chowdhury—someone who seemed to speak extemporaneously but actually prepared carefully, arranging everything neatly before delivering it.

People thought he was just speaking off the cuff, eloquently and spontaneously, but in truth, his lectures were thoughtful because there was preparation behind them. And he gave that preparation his full attention. I realised then, as a young person, that this was the secret behind his so-called "spontaneous" speeches. Spontaneity doesn't just happen—you need practice behind it. That lesson has stayed with me to this day. His attention was spread across many areas—not just as a writer, translator, or teacher, but also in cultural activities. He would give speeches, and he would encourage others too.

Munier Chowdhury's extraordinary contributions—not only through his own work but also by inspiring others and engaging in dialogue—made him unique. Those of us around him benefited immensely. He was simultaneously a teacher, playwright, translator, actor, and broadcaster.

Many have written about Mir Mosharraf Hossain, but Munier Chowdhury's writing stands out as extraordinary because of the way he perceived and analysed Mosharraf Hossain—something lacking in others.

Some say that, in his later years, he lived with much gratification and allure, viewing this as a deviation—but I see it not as a deviation, but rather as his defining trait, a mark of his development. I believe he defined his own role. During his student life, he was indeed associated with the Communist Party and was involved with the Dhaka branch of the Progressive Writers' Association. He also spent time in jail for his participation in the Language Movement. But later he realised that he could no longer play that political role. Because of this, he shifted his focus towards academic and cultural roles.

For that reason, he went to America, driven by curiosity to understand the world better, which broadened his perspective. I do not consider this a deviation but rather a realisation that after spending so much time in politics, continuing in that role was no longer feasible for him.

An example from our English Department at Dhaka University was Professor Amiya Bhushan Chakraborty, who was a member of the Communist Party but left before the Language Movement upon sensing the situation. He then went to Kolkata as a refugee, became the principal of a college there, and later joined the Naxalite movement. But for Munier Chowdhury, playing that political role was not possible. He was deeply rooted in his family bonds, especially with his sister Nadera Begum, who was also involved with the Communist Party during her student days and spent considerable time in prison. She later became a teacher in our department.

I think it was possible for Munier Chowdhury to continue his intellectual work, but due to changing political roles, he had to move in a new direction. He was not like Shahidullah Kaiser or Ranesh Dasgupta, who were ready to go back to jail again. Going to jail again would have been futile for him. Instead, he managed to accomplish many important tasks during that time.

In 1971, we were still in the same neighbourhood. But after March 25, we were all scattered. Munier Chowdhury went to his father's house in Dhanmondi—now known as Bhuter Goli. His family home was there, so he moved in. We all went off to different places. I didn't stay on the university campus anymore because one of our relatives, who worked in intelligence with the police, told me right after the crackdown that they had been sent a list of ten teachers' addresses. And there I was—my name right in the middle of it. He told me, "Your name is on the list." So, I understood immediately. On December 14, Al-Badr came to Munier Bhai's house and found him there. Anwar Pasha, on the other hand, had moved into a supposedly safer house after leaving Nilkhet, but on December 14, Al-Badr came to that house and took him. Rashidul Hasan of the English Department was there having breakfast with Anwar Pasha. Both were captured.

In many ways, Munier Chowdhury was like the "full man" of the Renaissance—multifaceted and deeply engaged. He was warm-hearted, kind, and inspiring. The loss of someone like him cannot be measured—personally, collectively, or culturally.

Serajul Islam Choudhury, emeritus professor of Dhaka University, is one of Bangladesh's most prominent public intellectuals.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments