The dangerous illusion of bank bonds

At its core, banking is about pricing and managing risk. Trouble begins when risk is quietly recycled within the system rather than reduced or spread adequately across the board. In trading bonds, that is increasingly what is happening in the country’s banking sector.

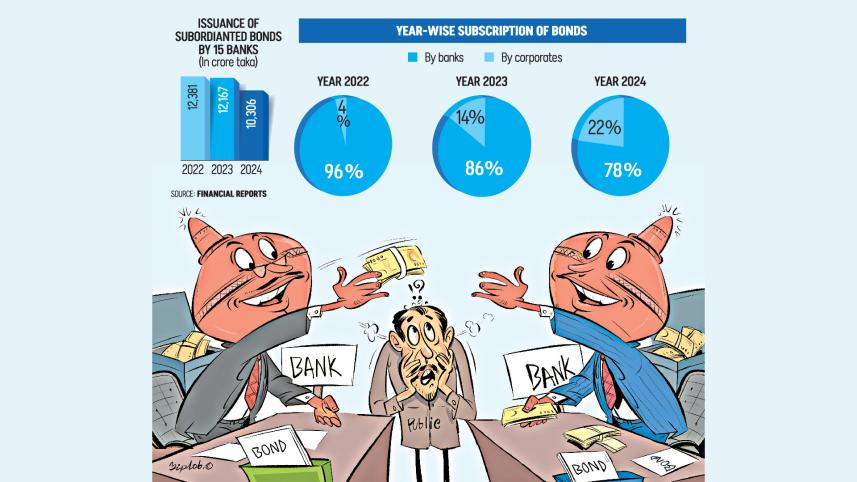

Commercial lenders issue subordinated bonds and buy them from one another to strengthen capital in line with regulatory requirements.

While this boosts capital ratios on paper, it does not attract funds from corporates or individual investors to the desired level, which goes against the very purpose of bank bond trading. The practice keeps risk tightly concentrated within the banking sector.

Put simply, it is like households in a neighbourhood lending to and borrowing from each other, rather than spreading risk by transacting with better-off groups. The exposure does not vanish; it just circulates.

In the three years since 2022, banks accounted for around 80 percent of subordinated bond investors, according to official data. The consequence hit three years later, when the Bangladesh Bank in 2025 put five ailing lenders in the merger process.

Of them, four banks collectively owe institutional investors about Tk 2,900 crore in Mudaraba subordinated bonds and more than Tk 1,000 crore in Mudaraba perpetual bonds.

That enormous Tk 3,000 crore could simply disappear from the books, since bond investments do not have the insurance protection deposits enjoy.

RISK BUILDING INSIDE

Under banking regulations, subordinated bonds count as Tier-2 capital. In the event of a failure, these bonds are repaid only after depositors and senior creditors, making them higher risk and higher return than deposits.

Banks deduct subordinated bonds from their demand and time liabilities but lend using the bond proceeds. This can worsen liquidity mismatches in a fragile banking system.

When banks subscribe to one another’s bonds, no fresh capital enters the sector. Even when corporates appear to buy bonds, many of these investors are provident funds of other banks, keeping exposure within the system.

“Deposits of one bank are effectively being shown as capital of another,” said AF Nesaruddin, former president of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Bangladesh (ICAB). “That erodes the quality of capital.”

The Bangladesh Bank has previously recognised the danger of direct cross-buying, where two banks subscribe to each other’s bonds. The banking regulator instructed banks to avoid such transactions to limit contagion risk.

Banks then adopted somewhat a circular subscription, according to data.

Under this arrangement, Bank A buys Bank B’s bonds, Bank B buys Bank C’s, and Bank C buys Bank A’s. While technically compliant with the rules, the effect is much the same.

“It keeps almost the same risk within the system,” said Asif Khan, president of CFA Society Bangladesh, a platform for practitioners in the investment and fund management industry.

“If one bank fails, the stress spreads to others,” he added.

Khan said the practice goes against the spirit of the central bank’s directive but said banks are driven into it by a lack of investors. According to him, strengthening the demand side of the bond market could resolve the problem.

BANKS ARE NOT THE VILLAINS

Bankers and analysts say heavy reliance on bank-to-bank bond subscriptions is caused by a weak bond market rather than reckless behaviour by the lenders.

The country’s bond market has historically been thin, with limited liquidity and a narrow investor base. Although some subordinated bonds are listed on the stock exchange, trading is rare, making exits difficult.

As a result, individual investors shy away, while corporates hesitate to lock funds into long-term instruments.

Interest rates also work against bank bonds. In recent years, yields on risk-free treasury bills and bonds have exceeded returns on subordinated bank bonds.

“Why would investors subscribe to subordinated bonds when treasury rates are higher?” said Tanzim Alamgir, managing director and chief executive officer of UCB Investment Limited, which manages around 50 subordinated bonds.

Shah Md Ahsan Habib, a professor at the Bangladesh Institute of Bank Management (BIBM), said the lack of institutional investors leaves banks with few options.

“There are no vibrant bond markets and no institutional investor base, so banks are forced to go to other banks,” he commented.

Syed Mahbubur Rahman, a former chairman of the Association of Bankers, Bangladesh, said banks have limited scope to sell subordinated bonds to corporates.

“Corporates are reluctant to invest in long-term instruments, while individual investors want liquidity,” said Rahman, who is also the managing director and CEO of Mutual Trust Bank.

THE SCALE OF EXPOSURE

According to an analysis of 18 banks’ 2024 financial statements, around 80 percent of subordinated bonds were subscribed by other banks, while the rest went to corporates.

Among corporate subscribers, provident funds of banks still accounted for a large share.

In 2022, banks accounted for 96 percent of subscriptions. The ratio fell to 86 percent in 2023, showing a gradual rise in non-bank participation, though the market is still heavily skewed towards banks.

Of the 18 banks, Pubali Bank attracted the highest share of corporate subscribers at 65 percent. Nine banks failed to attract any corporate investors at all.

According to 2024 data, Agrani Bank subscribed Tk 350 crore of Mudaraba subordinated bonds issued by Exim Bank, while Standard Bank invested Tk 125 crore.

More than half of Exim Bank’s bondholders are now banks facing potential losses.

Mudaraba bonds issued by First Security Islami Bank and Union Bank were fully subscribed by other banks.

Since 2016, banks have issued subordinated bonds worth more than Tk 35,000 crore, according to the Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission (BSEC).

WHAT REGULATORS ADMIT

A senior central bank official said the regulator ordered banks to include corporate subscribers after realising that bank-to-bank subscriptions weaken capital quality.

Arief Hossain Khan, spokesperson for the Bangladesh Bank, said subordinated bonds allow banks to reduce their capital deficit.

“It is true that when a bank invests in another bank’s bond, it ultimately sends deposits to capital, which is not happy information. So, the central bank is considering this and trying to increase participation of corporates instead of banks,” he added.

Abul Kalam, spokesperson for the BSEC, said subscriptions by banks do not create real capital, even though they count as Tier-2 capital.

“Deposits of one bank are shown as capital of another,” he said.

He added that small savings and corporate funds need to be channelled into bonds for the proceeds to qualify as genuine capital.

While BSEC requires bond issuers to list, a lack of buyers due to low trust in issuers remains a problem, added Kalam.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments