“Why should I leave?” The Partition in the cinema of Ritwik Ghatak

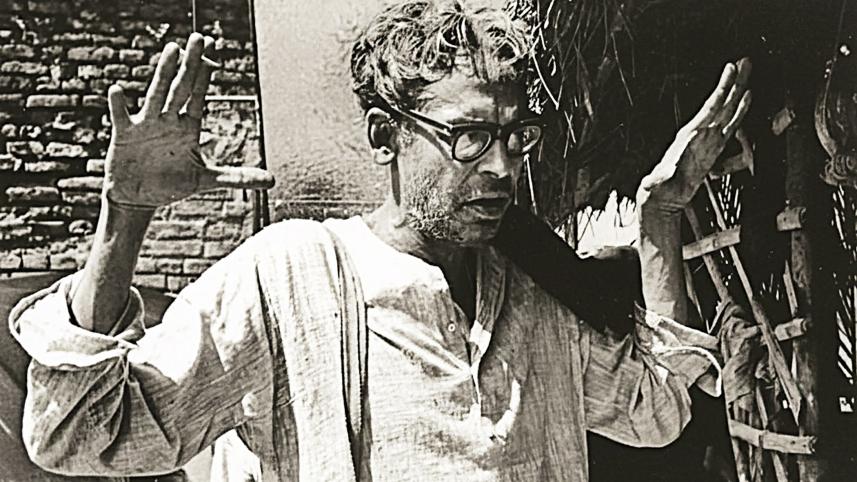

Author, playwright, and film director Ritwik Kumar Ghatak was born on November 4, 1925, to Rai Bahadur Suresh Chandra Ghatak, district magistrate, and Indubala Devi. During the 1940s, the Ghatak family, originally from Dhaka, relocated—first to Berhampore, and later to Kolkata. Ghatak was profoundly affected by the social and political events of the 1940s—the Second World War, the Great Bengal Famine, and, particularly, the Partition. His fiction, the plays he composed for the leftist collective—the Indian People's Theatre Association—and his films chronicle the upheaval caused by the Partition, the displacement of numerous Hindu families from eastern Bengal to India, and the ensuing crisis of a syncretic Bengali culture.

Beginning with Ramu's multiple relocations in Nagarik (The Citizen, 1952, released in 1977) and his mother's dreams of a better home, many of Ghatak's films allude to the Partition, but it is Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star, 1960), Komal Gandhar (E-Flat, 1961), and Subarnarekha (1962, released in 1965) which constitute his Partition trilogy. His contemporary Satyajit Ray noted in the foreword to Ghatak's Cinema and I that "Thematically, Ritwik's lifelong obsession was with the tragedy of Partition. He himself hailed from what was once East Bengal, where he had deep roots. It is rare for a director to dwell so single-mindedly on the same theme; it only serves to underline the depth of his feeling for the subject." Film scholar Bhaskar Sarkar has described him as "the most celebrated cinematic auteur of Partition narratives" (Mourning the Nation).

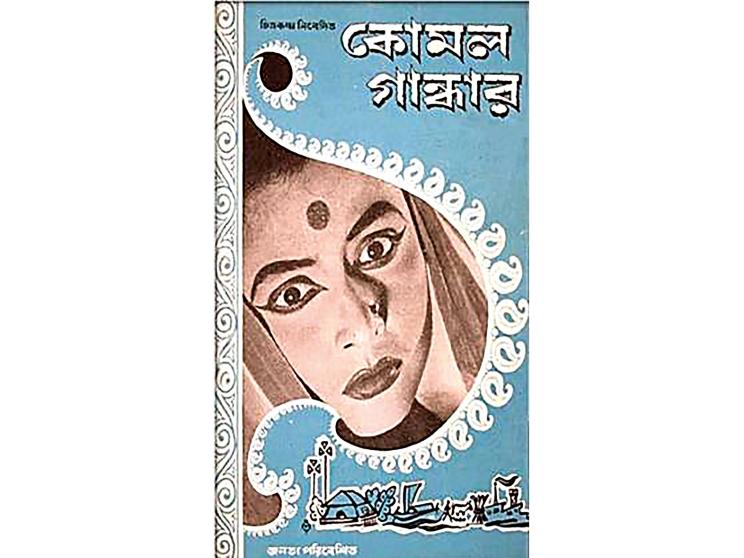

Ghatak's Komal Gandhar opens sometime after Partition with the "Niriksha" theatre troupe staging a play. In the play, an elderly man speaking an East Bengali dialect of Bangla asks angrily, "Why should I leave?" adding, "Why should I leave behind this lovely land, abandon my River Padma, and go elsewhere?" His interlocutor tells him that emigration is his only chance of survival and advises him to register as a refugee. The old man responds with only a string of "chhee!" (shame). While this proceeds in the foreground, a steady stream of human silhouettes treks across the white screen in the background, evoking refugee migrations.

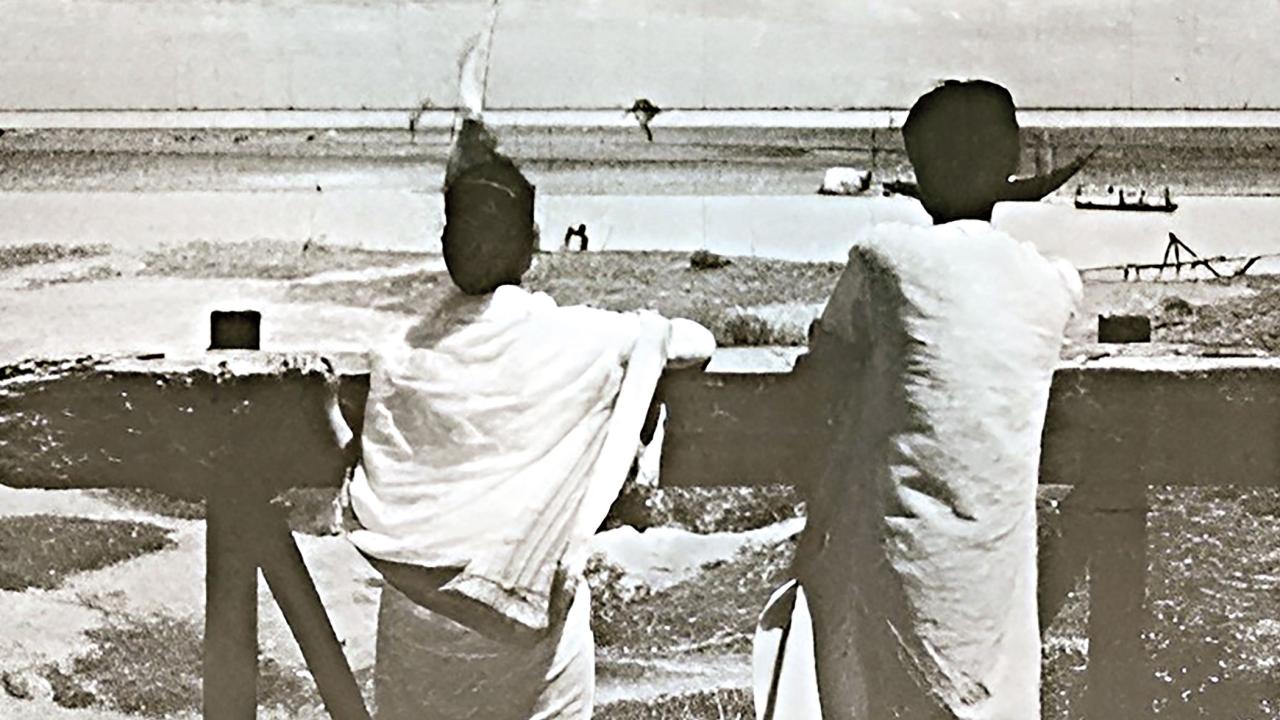

The agony over Partition-related uprootings from home and homeland suffuses Ghatak's cinema. If the above scene dramatizes the torment of emigrating from the land of one's birth, a later sequence in the film captures the melancholy of the displaced. Actors Anasuya and Bhrigu (who plays the reluctant migrant in the opening scene) arrive in Lalgola, where they are scheduled to perform. Lalgola is an Indian border town situated on the banks of the Padma. The two pause on the riverbank at a set of stopped train tracks and gaze meditatively across the waters into the far horizon. Then, Anasuya says, "On the other side of the river is East Bengal, you know! … Somewhere on that bank is my ancestral home. … The word, I think, is tranquillity. That's what my grandma used to say, and that tranquillity, it seems, is something we'll never get back. … Whenever I think of home, the waters and the little crossings come to mind."

They wander along the riverbank. Then, after a long pause, Bhrigu replies: "My ancestral home is also over there. There—you can see the houses. So close, and yet I can never reach them—it's a foreign country. Do you know what I was doing when you said that somewhere on that side is your ancestral home? I was looking for my own home, because my home is there and nowhere else. On the train tracks where you and I were standing, there I used to get off the train from Calcutta. A steamboat would take me to the other side, where Ma would be waiting … The train lines, then, denoted a bond; now they mark a split. The land has been ripped in two."

For Anasuya and Bhrigu, like others displaced by the Partition of India, the ancestral homeland—their desh—is a place of memories: memories of childhood, memories of an accustomed way of life. It is also a place of tranquillity, a place whose topography and ecology were theirs. And it is a place they lost. Their desh—homeland or ancestral land—is now bidesh, foreign land, and inaccessible. The Partition wrenched apart Anasuya's and Bhrigu's birthplace from their homeland, rewriting in the process the histories and geographies of belonging.

Escalating communal hostilities in the Indian subcontinent during the mid-1940s reached their horrific climax in the Partition of August 1947. Decolonisation was achieved at the cost of partitioning the colony into India and Pakistan as sovereign nation-states. As a result of Partition, provinces were allocated to independent India or Pakistan according to a census logic of ethno-religious majoritarianism, with two provinces—Punjab in the northwest and Bengal in the east—being split between the two countries. The process of Partition was marked by unprecedented violence, violence that led to the largest migration in human history.

Countering Partition's logic of religious incompatibility, in Komal Gandhar Ghatak interlaces Muslim boatmen's songs with Hindu wedding songs to articulate a syncretic Bengali culture. The wedding songs, according to Ghatak, prefigure more than just Anasuya and Bhrigu's relationship: "I desire a reunion of the two Bengals," noted Ghatak in his 1966 essay Amar Chhobi ("My Films"), "hence the film is replete with songs of union." Similarly, Anasuya's mother, in her diary entry from November 1946 in the aftermath of the riots in Noakhali, quotes Tagore's lines "God, may the brothers and sisters in Bengali homes be united" from Banglar Mati, Banglar Jol ("Bengal's Soil, Bengal's Waters"), a poem composed to protest the first partition of Bengal in 1905. The lines testify to Ghatak's longing. (He stated, in an interview, "I am not talking about a political union of the two [parts of] Bengal … I am talking about a cultural [re]union.") The boatmen's "Dohai Ali" chant—"In the name of Ali" or "Mercy, Ali"—invokes protection against misadventures on the Padma's waters, and it returns in a subsequent scene, this time with women frantically pleading "Dohai Ali" as the camera speeds down the train tracks to the buffer on the disabled railroad (where Anasuya and Bhrigu were standing in a previous scene). When the camera encounters the buffer, the screen goes dark, indicating that "the old road to eastern Bengal has been snapped off" (My Films).

On April 14, 2008, Bengali New Year's Day (1415), train service between Dhaka and Kolkata was restored with the launch of the Maitree (Friendship) Express. Reporting on the event, The Times of India (April 15, 2008) noted that "Ritwik Ghatak's immortal scene from Komal Gandhar had captured the grief of a generation torn asunder by Partition and war. But had his protagonist Bhrigu lived now, his dream of reaching there wouldn't have remained just a dream."

If Komal Gandhar addresses Partition-related melancholia, Meghe Dhaka Tara explores the struggle for survival and the social crisis engendered by Partition, particularly its impact on the lives of women. In this film, Neeta's participation in wage labour is indicative of wider social changes ushered in by the Partition. The political and economic vicissitudes attending Partition compelled women in displaced families to pursue gainful employment. The family's economic collapse, whether due to looting or forced evacuation and the consequent loss of landed property, could be salvaged, at least partly, through women's labour in white-, pink-, and blue-collar occupations.

Like so much of Bangla literature of the period, Ghatak's cinema celebrates the quiet courage of these formerly homebound women who, without knowing or intending to, set off a transformation in the mindscape of both displaced and non-displaced women, especially middle-class women—making their employment outside the home socially acceptable. That Neeta, the elder daughter, becomes the family's economic crutch bears testimony to this.

However, Neeta's entrance into the labour market is tantamount to enslavement to the needs of everyone she loves. Overextending herself at work and living in insalubrious conditions, she contracts tuberculosis. The disease operates as a metaphor on two levels: (i) to intensify her feeling of entrapment within her needy family, where there is no air left for her to breathe; and (ii) to indicate a broader social rot, by which norms of ethical conduct and decency have withered away to the point that the compassionate and unselfish suffer. Displacement-induced poverty and the very real fear of starvation—fears stoked by memories of the 1943 Bengal Famine—compel Neeta's mother to plot to keep her daughter single. The family's survival depends on Neeta's earnings, so her mother refuses to let her daughter marry and take her salary elsewhere. With low cunning, she foils Neeta's romance with Sanat.

The shot of Neeta—tubercular and self-isolating—standing at the window of her room, watching her mother and siblings in the courtyard, with crisscrossing bamboo bars fragmenting her face, suggests her incarceration within the family, together with alluding to the Partition. Nurturing and generous but exploited and dying, she embodies post-Partition "crumbling Bengal" (My Films). The refugee woman as an analogue for Bengal reappears in Komal Gandhar in Anasuya's question when compelled to choose between Bhrigu and her fiancé Samar: "Am I also divided in two?" Similarly, about Subarnarekha, Ghatak writes that "The divided, debilitated Bengal that we have known … is in the same state as Seeta in the brothel" (My Films).

Finally, Neeta's words to her elder brother Shankar, when he visits her at the sanatorium—"Dada, ami je banchte boro bhalobashi" ("Dada, I really love living")—illuminate the resilience of displaced women who picked up the pieces of their broken lives and set about rebuilding new ones in new places, among people they had not known before—people who had different food habits and spoke a different dialect of Bangla.

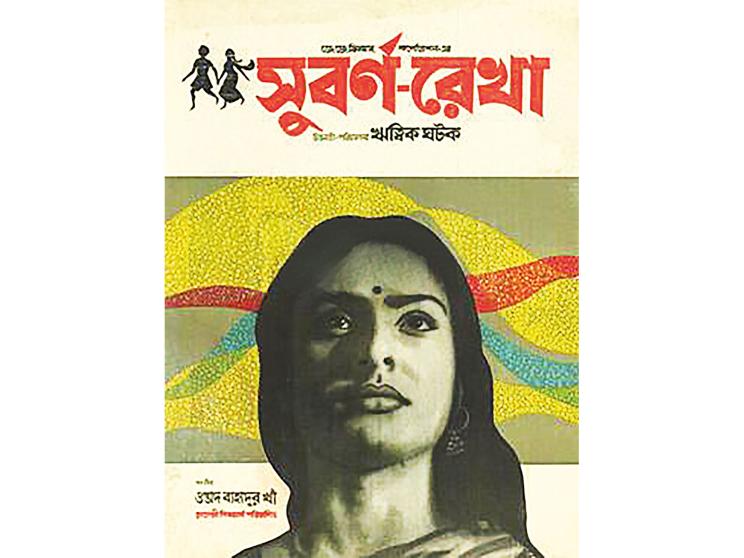

In Subarnarekha, the third film in Ghatak's Partition trilogy, ten-year-old Seeta asks if the Nabajiban refugee colony in Kolkata, where she has recently relocated with her brother Ishwar—her only surviving family member—is her new home. As her life unfolds, Seeta, like her mythical namesake, is serially displaced—from her village in East Bengal to the refugee colony in Kolkata, from there to Chhatimpur (her brother's workplace) on the banks of the River Subarnarekha in the interiors of western Bengal, and, eventually, to a refugee colony in Kolkata after she marries Abhiram. Seeta's question, "Is this my new home?" ricochets through the film, and when her son Binu asks Ishwar, "Are we going to our new home?" the plot suggests that the trauma of homelessness has filtered into the next generation.

In addition to the political division of Bengal, Subarnarekha also exposes other social fault lines—provincialism and caste. Kaushalya and her son Abhiram from Dhaka district are denied a place in the refugee colony because the occupants of that section are from Pabna; in a seemingly ironic reflection on the Partition, a former Pabna resident tells her, "What would be left of us if we can't even hold on to the differences between the districts?" But was the refusal of shelter based on Pabna–Dhaka differences alone, or was caste prejudice also in the mix, given that Kaushalya is of a lower caste? The disruptive potential of caste is brought up later in the film when Seeta's brother Ishwar, a Brahmin, learns that Abhiram, the child he adopted after his mother Kaushalya was abducted from the refugee colony, is of the Bagdi caste. Ishwar, worried that his "pious" employer might dismiss him for sheltering a lower-caste man and, further, to thwart his sister's romance with Abhiram (for the same reason), asks the latter to leave.

Subarnarekha brings to a full circle a question broached by the first film in the trilogy, Meghe Dhaka Tara—who is responsible for so much suffering? Upon learning of his daughter's tuberculosis, Neeta's father exclaims, "I accuse!" looking directly into the camera, his index finger also pointing towards it, thus including the viewer within the scope of his gaze and his accusation; but he withdraws it. Ishwar, on the other hand, drunk and sightless without his glasses, staggers into a brothel in Kolkata, unaware that he is his widowed and penniless sister's first client; upon seeing him, Seeta kills herself. (Ishwar's "He, Ram!" in response to her suicide connects her death with Gandhi's assassination and the political turmoil in the subcontinent.) After Ishwar's claim that he is guilty of murdering Seeta is dismissed by the court, he tells a journalist, "You are guilty too … you, me, all of us." The faltering "I accuse!" has transformed into a definitive assertion of collective responsibility for the making of a "divided, debilitated Bengal" (My Films).

I conclude with Ghatak's reflections on the condition of Bengal in the twentieth century:

In our boyhood, we have seen a Bengal whole and glorious. … This was the world that was shattered by the War, the Famine, and when the Congress and the Muslim League brought disaster to the country and tore it into two to snatch for it a fragmented independence. Communal riots engulfed the country. … Our dreams faded away. We crashed on our faces clinging to a crumbling Bengal, divested of all its glory. … I have not been able to break loose from this theme in all the films I have made recently. (My Films)

Ritwik Ghatak passed away on February 6, 1976.

Debali Mookerjea-Leonard is the Roop Distinguished Professor of English at James Madison University.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments