Where have JU’s winter birds gone?

On misty winter mornings, the lakes and wetlands of Jahangirnagar University once came alive in a breathtaking rhythm of wings and water. Floating lilies drifted across mirror-like surfaces as thousands of migratory birds from Siberia, Mongolia, China, Nepal and other colder regions swooped, dived and skimmed the glistening lakes. Their calls filled the air, turning the campus into one of Bangladesh’s most magical winter landscapes.

For nearly two decades, this spectacle defined JU’s winter. Now, the skies are quieter.

After 2020, regular observers began noticing a worrying pattern as the flocks steadily shrank. What was once a congregation of several thousand ducks has dwindled to only a few hundred this winter.

The familiar chorus of chirps and wingbeats has largely faded. Lakes that once teemed with life now feel eerily still, leaving students and nature lovers asking a troubling question: why are the birds no longer coming to JU?

Ferogenus Pochard

According to the university’s Department of Zoology, most of the migratory birds that visit the campus are duck species, including shorali, pochard, flycatcher, garganey, patari duck, waterfowl, khoyra and comb duck or nokta. Other regularly recorded species include manikjor, kolai, small nag, water pipit, wagtail, pipit, red turtle dove, baamunia duck, northern pintail and the rare sickle-crested duck, among many others.

Just a few years ago, around 6,000 to 7,000 migratory birds arrived on the JU campus every winter. Over the past three years, that number has dropped to 2,500–3,000, and this year it has fallen further to around 2,000. Last year, during November and December, birds were seen at WRC Lake, the Transport Chattar Lake and the lake near Al-Beruni Hall. This year, however, the latter two have remained almost empty.

Today, these fertile, food-rich lands have largely disappeared under mega housing projects and expanding human settlements. At least 80 percent of previously available waterbodies that once supported migratory birds have been lost.

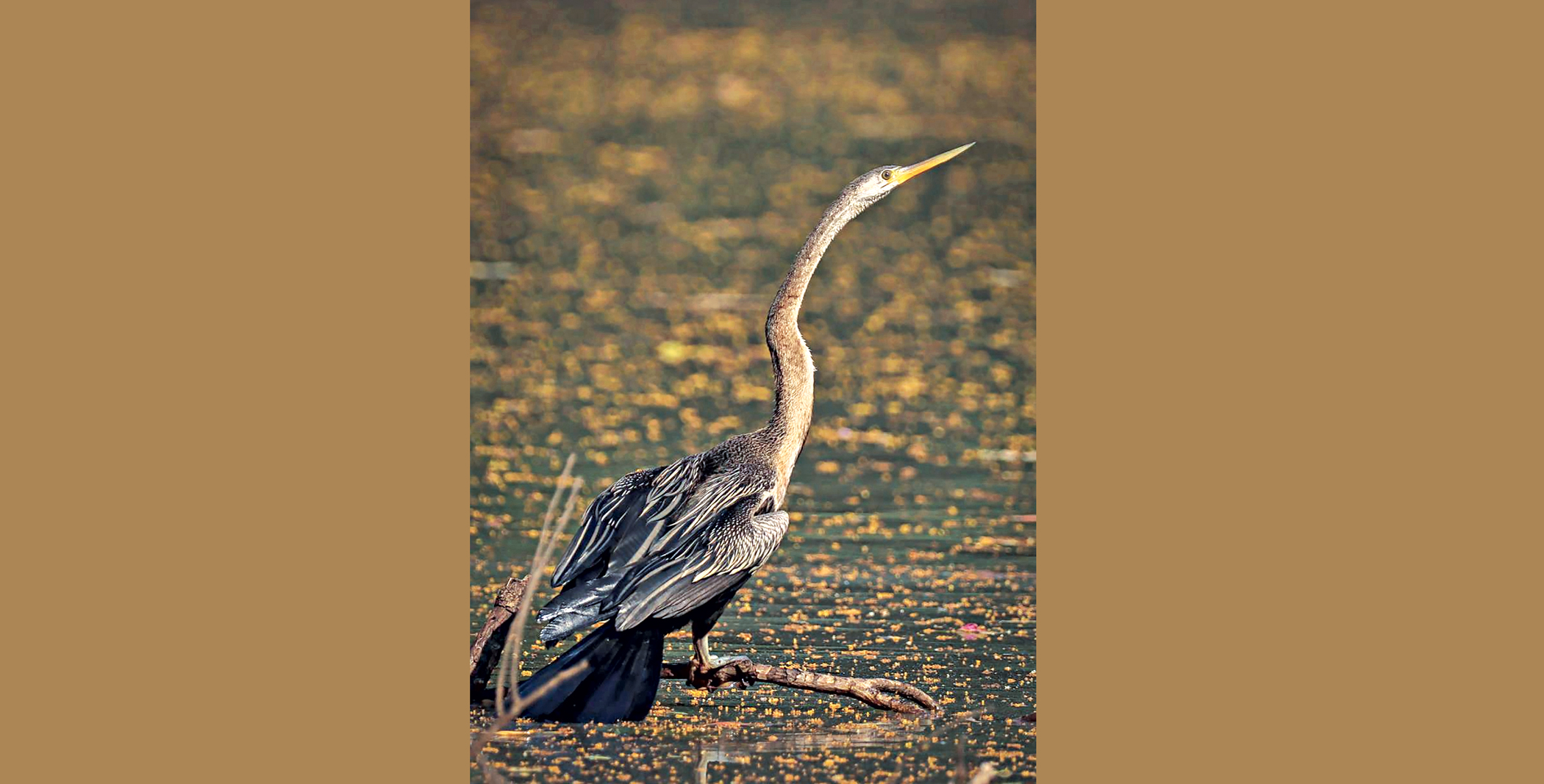

Dr Md Kamrul Hasan, a wildlife expert and professor of Zoology at JU, said the first flock of about 30-35 birds landed at the Wildlife Conservation and Study Centre (WRC) Lake on October 13 last year. By late October, the lake was full of birds. This year, however, only two lakes have hosted migratory birds. Besides WRC Lake, some birds have started using Joypara Lake, which was recently cleaned.

Oreintal Darter

He noted that during the quiet period of the pandemic in 2019–20, about 6,000 birds were counted across JU’s lakes during the December peak. In normal years, the number ranged between 4,000 and 4,500. In recent years, however, the decline has been alarming.

“Jahangirnagar University is now going through an overall ecological decline, and migratory birds are disappearing as part of that process,” Dr Hasan said.

Conservationist Aurittro Sattar, who grew up on the JU campus, has also documented species that have stopped visiting altogether. These include the African knob-billed duck, cotton pygmy goose, common teal, yellow-wattled lapwing and several bush birds such as the Siberian rubythroat, Siberian stonechat, Bengal bushlark, yellow-crowned babbler and Eurasian wryneck.

Raptors like the long-legged buzzard, white-eyed buzzard and crested serpent eagle have also declined sharply.

Lesser Whistling Ducks

Aurittro, a student of the Department of Environmental Sciences and a wildlife photographer, said last year the Zoology Department documented nearly 3,000 migratory birds, most of them around the WRC lakes. The lakes near the administrative building and transport area used to host about 500 birds, but this year that number has dropped to almost zero.

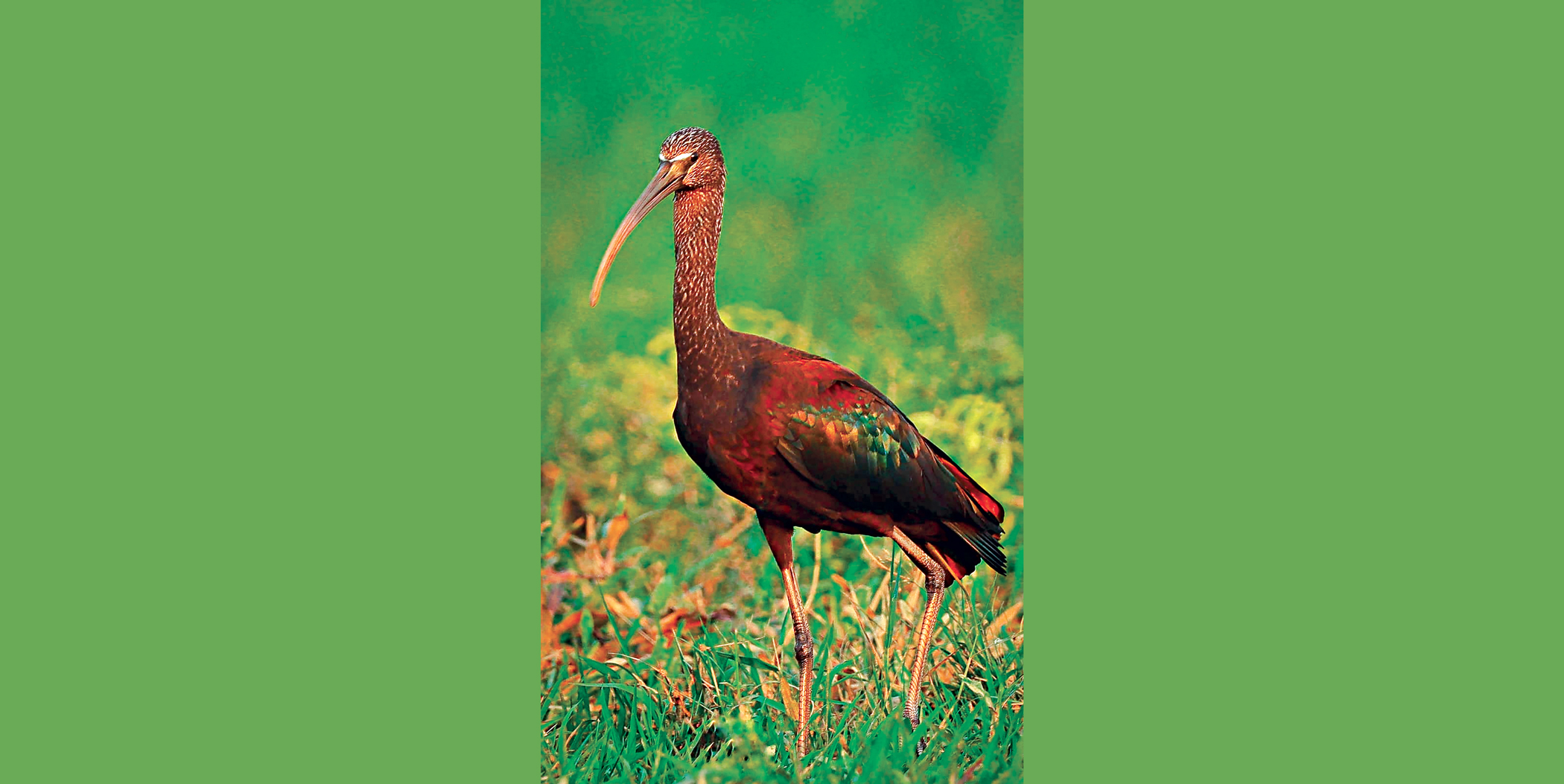

A recent field visit to WRC Lake and the Swimming Pool Lake found glossy ibis (khoyra kastechora), fulvous whistling duck (raj shorali), lesser whistling duck (pati shorali) and garganey.

Native Asian openbill storks were also seen, along with raptors such as the changeable hawk-eagle and oriental honey buzzard. For brief periods, greater spotted eagles, Indian spotted eagles and booted eagles were also observed.

“These birds we are seeing now belong to the third or fourth wave of migration,” Aurittro said. “They are only coming to WRC Lake because it has minimal human disturbance and has been kept in a natural condition.”

Glossy ibis

While experts point to campus-level pressures such as unplanned high-rise construction, delayed lake restoration, deforestation, leasing out lakes for fish farming and increased human activity, ornithologist Dr Reza Khan said the main cause lies far beyond the JU campus.

“Migratory ducks do not choose roosting sites randomly,” Dr Khan said. “They need feeding grounds within about 10 kilometres. If those wetlands disappear, birds will not return to roost during the day because their night-time feeding becomes impossible.”

In addition to man-made problems such as alteration of natural waterbody features, changes in landscape patterns and the creation of obstructions in aerial flyways, Dr Khan said the most significant factor has been the complete or near-complete disappearance of low-lying areas surrounding Dhaka city and its suburbs, including Savar, Tongi, Purbachal, Badda and Demra.

Previously, he said, after floodwaters receded during October and November, vast, partially submerged lands supported Aman paddy cultivation alongside numerous species of grasses, reeds and wetland, aquatic and semi-aquatic vegetation.

These extensive wetlands sustained hundreds of species of microscopic and macroscopic plants and animals, which in turn provided abundant food for migratory ducks, geese, other waterfowl, as well as waders and shorebirds.

“Today, these fertile, food-rich lands have largely disappeared under mega housing projects and expanding human settlements,” Dr Khan said. “At least 80 percent of previously available waterbodies that once supported migratory birds have been lost.”

He said the JU campus now provides shelter but very limited food to 5,000-10,000 sharali, or lesser whistling ducks, and a few other duck species.

“This single factor -- the unavailability of large low-lying areas rich in aquatic and semi-aquatic plants and animals -- is the main cause of the disappearance of 50–70 percent of sharali from the Jahangirnagar University campus,” he said.

However, he noted that a significant portion of the population has shifted its roosting sites to low-lying, vegetation-rich wetlands between Dhamrai and Kalampur.

“These adaptable ducks have repeatedly changed their daytime roosting sites over time,” Dr Khan said. “During the mid-1980s to 1990s, they moved from the Dhaka Zoo ponds to the Botanical Garden lakes. By the early 2000s, they shifted to the Ceramic Factory lakes at Mirpur. By 2004–2005, they relocated to Jahangirnagar University and nearby low-lying areas.”

“They will eventually disappear from greater Dhaka once the remaining low-lying wetlands are converted into housing or industrial developments,” he warned. “Nevertheless, a few thousand individuals may continue to survive in small lakes and ponds that persist despite ongoing development, mostly as resident pairs or small flocks.”

“In short, if the feeding grounds disappear, the ducks disappear,” Dr Khan said. “No amount of lake beautification inside the campus can change this reality.”

To attract large flocks of sharali and other ducks and water birds, he said, it is essential to conserve and restore large, undisturbed expanses of waterbodies containing diverse aquatic vegetation, some for feeding and others for daytime roosting.

Field observations show that although the administration cleaned lakes and built bird platforms in previous years, very little was done this winter, apart from one lake-cleaning initiative supported by the university’s central students’ union.

Estate officer Abdur Rob admitted that responsibility lies partly with the university.

“Our budget for lake excavation and bird conservation is inadequate. New buildings, increased human pressure, uncontrolled tourism and open access have damaged bird habitats. We could not properly preserve the lakes that used to be their shelters,” he said.

Still, he remains hopeful.

“In recent days, birds have started returning slowly. If we follow expert guidance, some of the old natural environments can be restored,” he said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments