‘Tamasha’ and the long road back to ourselves

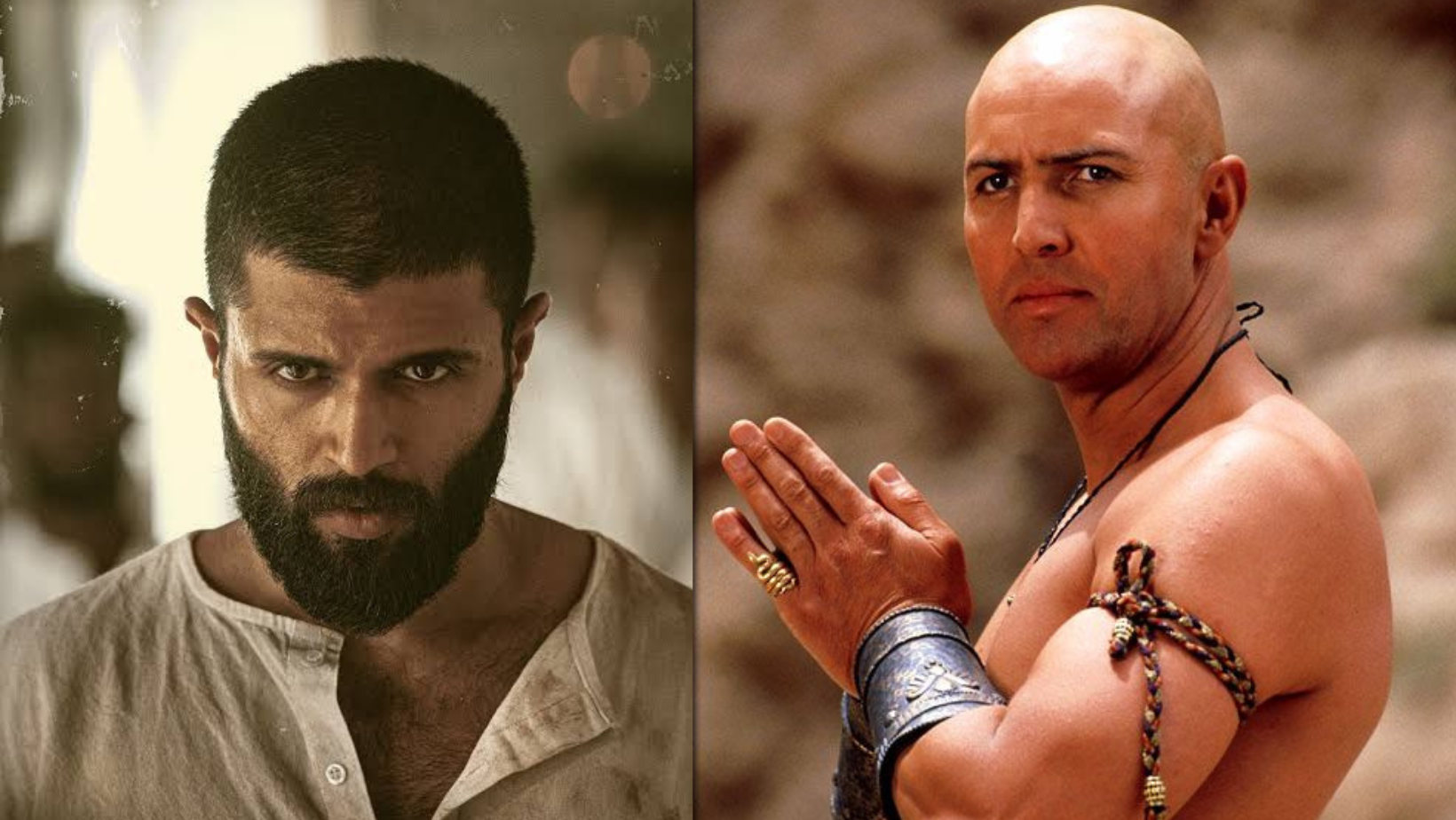

Some films slip into your life so quietly that you do not realise when they stop being stories and start becoming mirrors. "Tamasha" has that unusual ability. The first time you watch it, it feels like a love story with a quirky adventure at the start. But the more your own life begins to scatter into contradictions and compromises, the more Imtiaz Ali's world starts sounding familiar. He shaped it like a quiet confession disguised as a love story, and the confession unfolds layer by layer through the lives of Ved and Tara. The plot looks straightforward from a distance, but once you step into it, the film begins to pull apart the many selves a person learns to wear. Hence, a decade after its release, it still feels like a story that knows its audience far too well.

The story opens in Corsica, where Ved and Tara meet under an agreement that creates a strange kind of freedom. They treat each other like characters rather than people with history, and this choice becomes the heartbeat of the film. In that temporary space, Ved behaves like someone who has escaped the gravity of his routine life. He becomes playful, spontaneous, almost mythic in his energy. Tara responds with an openness that feels rare in Bollywood romances. Instead of falling for him in a predictable arc, she grows curious about this version of him that does not seem shaped by fear or habit. Their bond forms through mischief, stories, lies that carry no harm, and an intimacy that feels both childlike and profound. When they part ways, the film shifts into its true form. Tara spends the next few years carrying Corsica in her memory as she has seen a part of Ved that reveals something universal about people—the self that emerges when there is no script to follow. By the time she meets him again in Delhi, the story leans into its central tension. The Ved she encounters belongs to an entirely different world. He moves with measured politeness, keeps conversations small, and carries an invisible fatigue that feels older than him. The contrast between the two encounters relies on the quiet ache of seeing someone dim their own light.

Tara's confusion becomes the lens through which the story deepens. She remembers the storyteller, the improviser, the man who laughed without checking the room. Now she stands before someone who seems to live inside a pre-approved version of himself. Her longing for the Ved she met years ago comes from seeing a human being shrink under the expectations that built him. She tries to reach the part of him that once moved with instinct, and her attempts gradually stir the internal storm Ved has kept sealed. The narrative then pivots toward Ved's inner world. His childhood visits to the roadside storyteller begin to resurface and these memories serve as clues to how Ved learned to interpret the world. As a child he absorbed stories not as entertainment but as a way of making sense of identity. The storyteller's tales blur myth and reality, and the boy listening grows up believing that life, too, must follow a story path; one predetermined, one already laid out. The adult Ved tries to follow that path, yet something inside him rebels. The film explores that rebellion with unsettling honesty. Ved moves through his job like an actor trapped in the wrong play. He follows instructions, maintains perfect manners, and tries to be the dependable person the world rewards. Meanwhile, the storyteller inside him keeps knocking. His anger surfaces in bursts, his humour appears at odd moments, and his sense of self keeps tilting between control and chaos.

Tara's presence intensifies the fissures in him. She becomes a reminder of the person he once allowed himself to be, and that reminder forces him to confront the distance he has travelled from his own instincts. One of the story's most compelling threads is watching Ved attempt to understand why he split into two personas in the first place. His behaviour with Tara is inconsistent because he is wrestling with parts of himself that have lived in separate rooms for too long. As this turmoil escalates, the film returns to the figure of the old storyteller. Ved seeks him out in a moment of desperation, and this meeting becomes the emotional hinge of the entire narrative. The storyteller challenges him, provokes him, forces him to admit the truth he has been circling. Ved realises that he has been living inside a story not written by him, following a script handed down through years of approval and fear. The real story, the one that feels alive, has been waiting inside him, outlined in sparks, pulled forward by Tara, anchored in childhood memories.

This realisation does not turn him into a new man; rather it allows him to piece together the fragments he abandoned. The child who loved stories, the young man who danced through Corsica, the corporate employee who followed the rules—they all belong to him. He does not transform through a dramatic epiphany; he gradually learns how to honour the storyteller within him, how to reclaim imagination without discarding responsibility, how to live without suffocating the instinct that once made him feel alive. Tara remains central throughout this transformation, as a witness who stands by him with the kind of patience that comes from understanding rather than idealising. She loves him through confusion, through awkwardness, through the moments he pushes her away because he does not know how to hold himself together. Their relationship becomes the canvas on which Ved paints his rediscovery, and the story gives both characters space to breathe, break, and rebuild.

The conclusion gathers all these threads into a single moment of clarity and "Tamasha" endures because its story taps into a quiet fear many people carry; the fear of drifting so far from themselves that they forget the original spark. The film does not blame anyone for this drift. It simply observes how people learn to perform versions of themselves to survive, and how that performance becomes a habit that begins to feel like reality. Ten years have passed since the film was released, and that distance brings a clarity the initial viewing did not offer. The themes feel sharper now because the world outside feels noisier and more demanding. The pressure to perform identity, to edit yourself for acceptability, to tuck away the parts that don't fit, has only intensified. In that landscape, Ved's journey feels achingly contemporary. You start to see pieces of him everywhere: in friends who gave up their inner calling, in colleagues who move through life on autopilot, and sometimes in the mirror.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments