‘Pawmum Parban’ brings Mro children’s stories to Dhaka

There are exhibitions you walk into, and there are exhibitions that feel like you are stepping across a threshold into someone else's world. "Pawmum Parban", currently underway at Alliance Française de Dhaka, unfolds like the latter; carrying a depth that quietly rearranges how you look at a culture you thought you vaguely knew. I went in expecting an art show and left with the sense that a small group of children from the hills had succeeded in doing something the city often fails at: making us feel something beyond our own noise.

"Pawmum Parban" is a week-long cultural festival featuring Mro children and community members from Lama in Bandarban. The festival began on December 17 at the organisation's Dhanmondi premises and will continue until December 24, offering visitors a chance to experience Mro language, art, music, and cultural heritage in the capital.

Organised by Pawmum Tharkla, a community-led school founded over a decade ago in Lama, the festival marks the first time that many of the participating children have travelled outside the hills. The school began in a small bamboo hut and continues to work towards preserving the Mro language, early childhood education, and cultural practices at a time when indigenous languages and traditions across the Chittagong Hill Tracts are increasingly under strain.

The Alliance Française courtyard currently hosts a pocket of imagined hills; mountains sketched across the backdrop, clouds drifting in soft outlines, birds mid-flight. The lights are hung low and warm, almost domestic, as if they belong to a village evening rather than a Dhaka arts venue. Inside the gallery space, children's drawings line the walls. Some illustrate valleys and flowers from Lama; others depict daily life in Mro homes, families in traditional attire, scenes from the community, and musicians holding the plung, the bamboo flute central to Mro musical tradition.

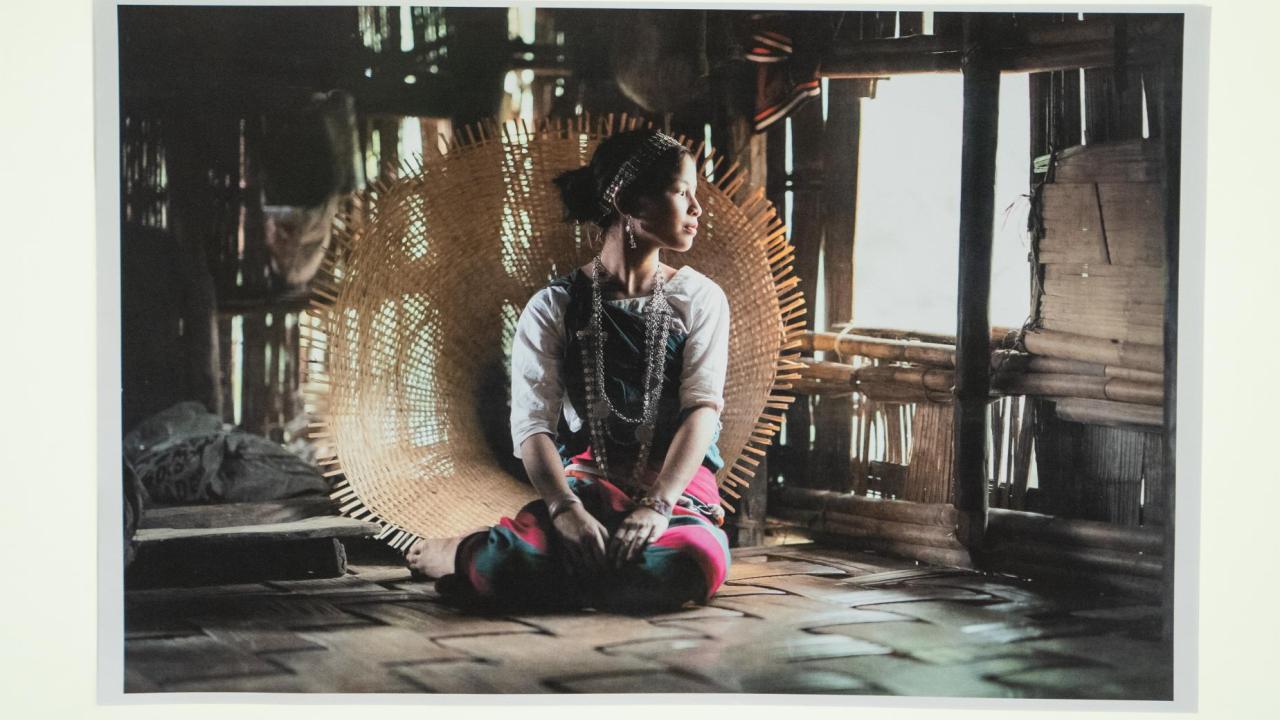

Hills appear again and again across the artworks, but each child draws them differently. Some are sharp, some soft; some filled with flowers, others dotted with houses clustered like families huddling together. Some drawings draw from local folklore, others from lived experience, and a few seem to hold stories the children do not yet have the words to narrate; so they sketch them instead. Photographs from Pawmum Tharkla school and Mro households are also on display, offering a visual record of the children's lives in the hills.

These are not illustrations of an anonymous landscape; they are personal geographies and small autobiographies disguised as art. There is something quietly disarming about seeing such grounded innocence displayed in a city that wears its ambitions like armour. What stands out most is that the exhibition does not place the Mro community behind glass for observation. Parents are present, walking slowly, looking at the drawings the way parents everywhere do; proud, amused, sometimes unsure why a particular scribble deserves wall space. Grandparents move from one frame to another with the patience of people accustomed to long rhythms. In between them are regular visitors, who gradually become part of this welcoming community.

The exhibition is part of a broader week-long festival that includes dance and song performances, cartoon and calligraphy workshops, guided tours, weaving demonstrations, and storytelling sessions involving both Mro children and children from Dhaka. A collaborative theatre production between the Mro children and Prachyanat Theatre is also part of the programme, alongside daily evening performances of traditional instruments.

Uthoiyoy Marma, chief organiser and co-founder of Pawmum Tharkla, explained that the festival is not about showcasing talent, but about visibility; about being seen as more than a footnote in the country's imagination.

"These are children who have grown up entirely in the hills and have never known what a city looks like; we wanted them to experience a different environment and bring their learning into the heart of the city," he said.

The journey of Pawmum Tharkla itself reads like a collective act of resistance against cultural erasure. The school started in a bamboo hut; without frills, endowed funding, or any promise of sustainability. What it had instead was a need: to preserve a language and cultural identity that rarely receives institutional support. Over the decade, artists, musicians, and educators from Dhaka made their way to Lama. Music lessons were shared, drawing workshops conducted, and storytelling approaches exchanged like gifts in an ongoing conversation. This year, the children are here, meeting the city on their own terms.

The organisers emphasise that, unlike many cultural festivals in the capital, "Pawmum Parban" has been arranged without major corporate sponsorship. Instead, it is supported largely by volunteers, partner organisations, and individual well-wishers committed to cultural diversity and indigenous rights. A small stall at the venue sells traditional woven garments, flutes, bamboo items, and other essentials, with all proceeds going towards the school fund.

Another co-founder, Shahariar Parvez, highlighted the school's long-standing collaboration with artists and educators from Dhaka. "We want to move across the entire landscape of the country with these children, so that they can draw every part of it, and grow," he said. Over the years, the school has welcomed musicians, visual artists, and cultural practitioners who have conducted workshops in Lama. This year, Cartoon People organised cartoon sessions for the children, while Prachyanat facilitated acting workshops.

For many visitors, the festival offers a rare opportunity to engage directly with the Mro community; one of Bangladesh's least represented indigenous groups – through creative work produced by the children themselves. Several Dhaka-based families attended the opening with their own children, many of whom joined the workshops and activities during the first two days. The events remain open to the public from 3pm to 9pm, and the community urges visitors to attend the exhibitions, meet the children and their families, and participate in the cultural sessions.

When I finally stepped out of the exhibition and back into the familiar chaos of Dhanmondi, the contrast felt sharp. Inside, the festival carried an unpolished sincerity; community-led, volunteer-supported, and built on belief rather than budget. Outside, the city buzzed with its usual restlessness, the kind that leaves little room for listening. Perhaps that is precisely the point of bringing "Pawmum Parban" here. The children did not come to impress Dhaka. They came to remind us that cultural diversity is not an abstract value, but a lived reality; shaped by people who rarely get invited to narrate their own stories.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments