Microcredit bank plan stirs debate over profit vs social goals

Bangladesh gave the world the model of modern microfinance, proving that poor people are creditworthy. The success of the Grameen Bank reshaped development finance globally. Now, the interim government led by Muhammad Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank, is seeking to push the sector into the next phase.

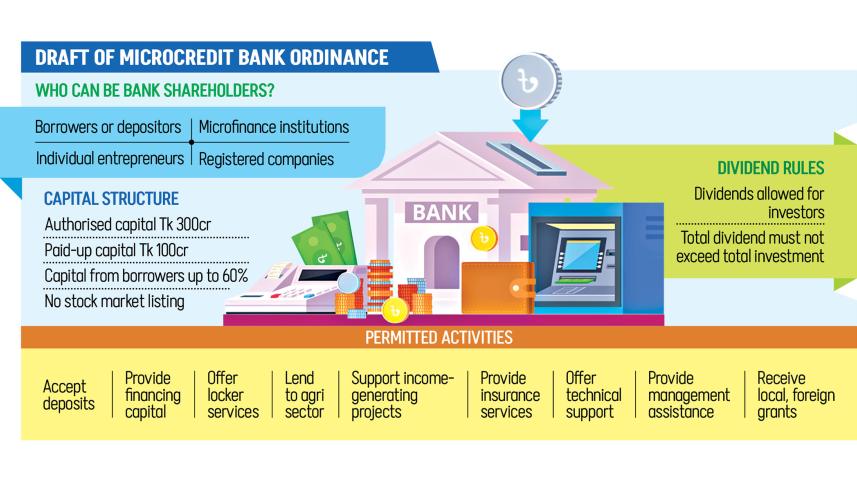

The target is to reach the 45 percent of adults who remain outside the formal banking system. To that end, the Financial Institutions Division (FID) has unveiled the draft Microcredit Bank Ordinance 2025, proposing a new tier of lenders called microfinance banks.

These institutions would combine the outreach of microcredit organisations with the services of commercial banks, offering products ranging from savings accounts to agricultural support, without collateral.

Zahid Hussain, a former lead economist at the World Bank's Dhaka office, described the proposed banks as a "progressive step".

"If they follow a social-business model and reinvest their profits, I don't see any problem," Hussain said.

At its core, the proposed banks would change how microfinance operates in Bangladesh. By allowing these new banks to accept shareholder investment and distribute dividends, the draft introduces profit incentives into a sector long designed around reinvestment and social outreach.

This shift has triggered strong resistance from the very institutions the model seeks to emulate. In a joint statement issued on Sunday, leaders of big microfinance institutions, including BRAC and ASA, warned that the draft ignores the "realities" of microfinance in Bangladesh.

A key point of contention is the distinction between "surplus" and "profit".

Microfinance institutions (MFIs) are not charities. They charge interest to cover operating costs and generate surplus income. Under the existing NGO-based framework, however, that surplus cannot be distributed. It must be reinvested to expand outreach or strengthen capital buffers.

The draft ordinance would alter this structure by introducing shareholder profit. As microfinance banks would operate on a commercial footing, investors would expect dividends.

Critics argue this creates an inherent tension. To maximise returns, management could face pressure to move away from lending to the "ultra-poor", who are costly and risky to serve, and instead focus on wealthier and safer borrowers. This potential "mission drift" is what sector leaders fear most.

The proposed capital structure has further unsettled institutions.

The draft requires each microfinance bank to have at least Tk 100 crore in paid-up capital. Up to 60 percent of this could be raised from borrower shareholders, with the remainder coming from other investors.

This presents a fundamental dilemma. Many microfinance institutions hold large asset bases but have no formal ownership structure capable of injecting equity.

To meet the capital threshold, they may be forced to sell stakes to individuals or corporate investors. Sector leaders fear this could shift control away from social objectives and expose the institutions to the same governance failures that have long plagued commercial banks.

Mohammed Helal Uddin, executive vice-chairman of the Microcredit Regulatory Authority (MRA), acknowledged that the draft, at which stage it is now, remains "incomplete", particularly on the question of how existing assets and liabilities would be converted into bank capital.

Some MFIs hold assets or liabilities worth Tk 30,000 crore to Tk 50,000 crore. The draft does not yet explain how these amounts would translate into paid-up capital, he said.

"That part is still missing," Helal Uddin admitted. "The draft will undergo further changes. That is why a technical group is already working on it."

Only after this process is completed, he added, would it be possible to assess the final shape of the ordinance.

Several broader questions also remain unresolved. If these entities continue to provide microcredit, how different will they be from existing MFIs? If they become banks, they would fall under the supervision of the Bangladesh Bank -- so what will their tax treatment be?

"There is still scope to work further on these issues, and that is exactly what the technical team is doing," Helal Uddin said.

"The Bangladesh Bank, the finance ministry and other stakeholders are also providing their opinions. Through this process, the draft will reach a more complete stage. Only then can it be judged whether this truly poses a concern for the sector."

Asked why major sector players were not consulted during drafting, Helal Uddin conceded that some institutions now objecting were not consulted, while stressing that discussions did take place with other stakeholders.

He also noted that once the law is finalised, detailed rules and regulations would be developed, which should clarify many implementation issues.

The draft defines microfinance banks as social businesses. Under this model, investors would recover their capital gradually through dividends over many years. In real terms, inflation would erode their returns. For example, an investment of Tk 100 recovered over 15 years would lose much of its value.

"If an investor cannot recover any part of the principal at all, then what incentive is there to invest? That question is still not clearly answered," Helal Uddin added.

REGULATORY DUALITY

Regulatory confusion is another flashpoint. The draft suggests licences would be issued by the Microcredit Regulatory Authority (MRA), raising the prospect of dual or even multiple oversight.

Mustafa K Mujeri, executive director of the Institute for Inclusive Finance and Development (InM), argued that if these institutions are banks, they should be regulated solely by the central bank.

"A dual system never works well," he said.

State-owned banks already operate under overlapping authority from the Financial Institutions Division and the Bangladesh Bank, and their performance has suffered as a result. Adding the MRA could introduce a third layer of supervision, further complicating oversight, Mujeri warned.

"In India, microfinance banks are regulated by the Reserve Bank of India. Bangladesh should proceed only after a sound and practical assessment," he said.

Mujeri also pointed to disagreement within the sector. "It should be examined whether any vested interest is influencing the process," he added.

Rather than moving quickly, he argued that policymakers should conduct a thorough assessment of whether the model would genuinely benefit poor borrowers.

On profitability, he was direct. "Anyone investing here would naturally expect dividends," Mujeri said. "If there is no dividend, why would someone invest? This issue requires much deeper examination before any final decision is made."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments