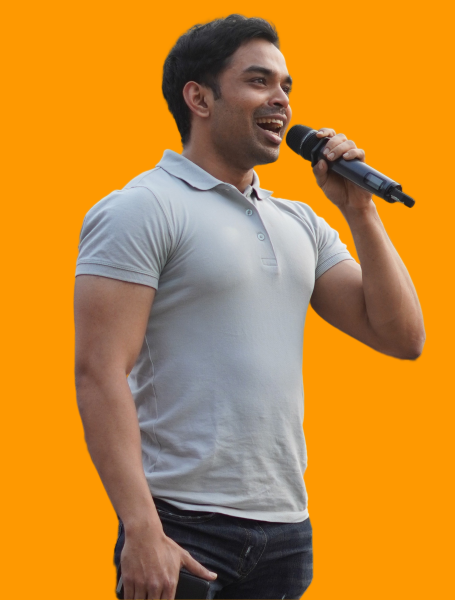

Why fitness fails without mindset, says Tanvir Hossain Britto

For Tanvir Hossain Britto, fitness did not begin as a career choice. It began as a coping mechanism.

“When I was 15 or 16, I was suffering from severe depression,” he says. “At that time, three things helped me immensely: fitness, meditation, and personal development books. These three things actually saved me.”

This origin story matters because it explains why Britto’s work has never been limited to muscle, weight, or aesthetics.

“Back then, I used to think every day might be my last,” he reflects. Recovery did not arrive through motivation posters or gym transformations. It came through routine, self-study, and mental grounding. “Since it helped me,” he says simply, “I thought it could help others as well.”

Today, Britto is a well-known certified fitness trainer, nutritionist, and personal development coach whose practice is grounded in lived experience rather than theory alone.

Learning the hard way and choosing science

Britto’s second turning point came years later, when he began training seriously around 2014–15. “Some local trainers gave me the wrong instructions, and it led to an injury,” he says. “I realised they did not really know much, and back then I did not know who else to ask in our country.”

Instead of quitting, he started studying anatomy, biomechanics, and exercise science.

“I tried to understand my own body and the science of exercise,” he explains. “Eventually, I fell in love with the knowledge.” What began as self-protection became a purpose. Teaching, he realised, could prevent others from repeating the same mistakes.

Why fitness fails when it is isolated

One of Britto’s strongest critiques of mainstream fitness culture in Bangladesh is how narrowly it is framed. “People view fitness as a separate compartment of life,” he says. “I believe fitness is holistic.”

He uses a striking metaphor to explain this. “Health and fitness are like the tectonic plates of our lives. When that is not right, we struggle with our careers and relationships.”

In his experience, physical and mental imbalance reduce a person’s ability to handle stress, decision-making, and emotional pressure. Fitness, then, is not about looking fit. It is about being able to function.

He is equally critical of blind imitation.

“People try to follow whatever they see online,” he says, “but there is a lack of education about how their own body works.” His coaching prioritises self-understanding over trend-following.

“It’s not just about what to eat or what exercise to do,” he adds. “It’s about building a mindset for long-term habits and lifestyle.”

Rethinking nutrition in a carb-centric culture

Nutrition is where Britto’s realism becomes most evident. In a country where rice dominates the plate, he avoids moralising food. “Our approach to food is driven by the palate,” he says. “We eat what tastes good. This is social conditioning.”

Rather than forcing rigid diets, he starts with willingness. “I first see if the person actually wants to change,” he explains. His method is habit-based, not restrictive. Protein intake becomes a key intervention.

“A person should consume at least 0.8 to 1 gram of protein per kilogram of body weight daily,” he notes, pointing out that many South Asians struggle with abdominal fat because of carb-heavy diets.

He teaches what he calls the Plate Method. “Divide your plate into four parts. One part protein, one part carbs, and half the plate vegetables and fruits.” It is simple, practical, and sustainable. Exactly how he prefers it.

Strength, especially for women, is not optional

Britto has worked extensively with bodyweight training, callisthenics, and hybrid movement systems. While he no longer runs Bengal Calisthenics as a standalone initiative, the philosophy remains central.

“I now use a multi-faceted approach,” he says. “Weight training, callisthenics, and Pilates. I customise based on the client.”

He is particularly vocal about dismantling myths around women’s strength.

“It’s just a mindset that we aren’t strong,” he says. “I have taught many female clients how to do pull-ups and push-ups. It is definitely possible with practice and the right technique.”

For him, strength training is not cosmetic. It is preventative, especially as women lose muscle mass and bone density earlier than men.

Teaching as purpose, not performance

What keeps Britto invested in coaching is not visibility or scale.

“When I teach, I learn a lot myself,” he says. “When I see people’s lives change, not just physically but in their habits and mindset, I feel empowered.” He calls this impact his real currency.

His advice to those considering unconventional careers is unromantic but honest. “The cost of entry is low. You can just start,” he says. “But the cost of success is very high.” It demands study, patience, and resilience. “If you worry too much about what society thinks, you can’t succeed in this industry.”

He is confident about one thing. “The fitness industry in Bangladesh is going to boom in the next five to ten years,” Britto says. “Those who start now will have the first-mover advantage.” For him, though, growth is secondary. Meaning comes first.

Photo: Courtesy

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments