Ending “youthwashing”, fixing education, rethinking skills

At a time when the Fourth Industrial Revolution is transforming industries and economic activity, Bangladesh’s education system is stuck in a foundational crisis—failing to ensure basic literacy, problem-solving ability, and employability for too many graduates.

More Young People, Fewer Skills

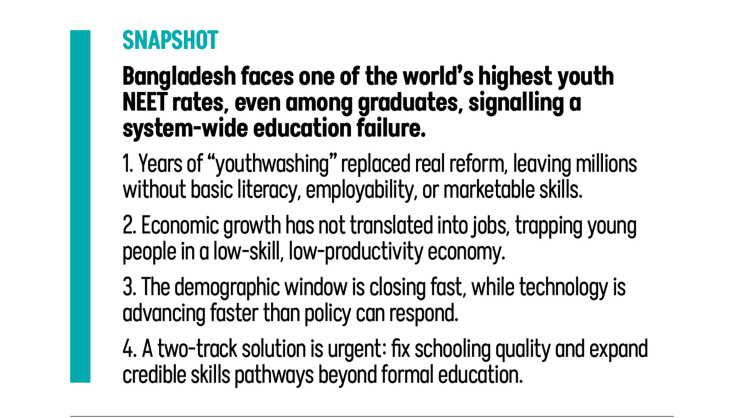

In 2022, almost two-fifths of our youth were not in employment, education or training, nearly double the global average of 21.7%. Even university graduates experience some of the highest unemployment rates. For those working, a significant portion is underemployed, performing tasks that are not commensurate with their degrees. This is not only a tertiary-education failure; it is a system-wide failure that begins early and accumulates over time.

The necessity for immediate, system-wide reform is underscored by the risk of losing the demographic window because the foundation is weak. Bangladesh’s youth population surged during the past 15 years (2009–2024), demanding the strongest possible base to prepare them for the 21st-century labour market. Instead, policies and politics failed them.

At a time when public education spending stagnated and remained among the lowest in the world, taxpayers’ money was wasted through symbolic budgetary allocations in the name of youth empowerment—a tragic phenomenon that I previously described as “youthwashing”. Rhetorical commitment without credible budgets, clear delivery plans, and measurable outcomes has left a generation dangerously exposed. Today millions have completed schooling without foundational qualifications; half of ten-year-olds cannot read an age-appropriate sentence; and Bangladesh remains near the bottom of global human capital rankings.

Bangladesh’s Double Hurdle

The country’s education and skills challenges have been compounded by jobless economic growth, leaving Bangladesh trapped in a low-skill, low-productivity economy. The tumultuous events of July 2024, which ushered in a new political dawn, were partly fuelled by a generation’s simmering frustration over exactly these challenges.

The past 15 years saw a troubling labour-market pattern: despite robust economic expansion and a tripling of exports in the Ready-Made Garments (RMG) sector, job creation has remained sluggish. This points to a growing disconnect between impressive GDP growth figures and genuine employment opportunities, making labour-market entry harder for new cohorts each year.

Regionally, Bangladesh’s competitors with similarly favourable working-age population ratios—Vietnam is the most obvious example—have begun reaping demographic dividends through sustained investment in education quality and workforce skills. This has helped keep economic growth steady while also expanding employment.

Meanwhile, disruptive technologies—generative AI, big data analytics, autonomous robots, additive manufacturing (3D printing), cloud computing, and the Internet of Things—are reshaping production and services, leaving Bangladesh even less time to upgrade human capital policies within the remaining demographic window.

Bangladesh is already decades behind in the global race between education and technology. The youthquake of 2024, arose from deep-seated disillusionment after years of unmet promises and policy paralysis in education and skills. As the nation looks toward a free and fair election and new political leadership in 2026, we must confront a “double hurdle” that young people face: low-quality schooling and limited pathways to acquire marketable skills outside the formal education system.

Policy Response

Beyond the necessary shift toward employment-led growth, millions of Bangladeshi young people must be equipped with the skills and credentials needed to avoid permanently missing the demographic window—and risking a demographic liability. If Bangladesh fails to act decisively, its demographic dividend window—expected to narrow sharply between 2030 and 2042—may yield not a boon, but a liability.

To make amends for past mistakes and overcome the “double hurdle,” Bangladesh needs a comprehensive, two-pronged human capital response: (1) fix the education foundation to raise learning and employability, and (2) expand credible skills pathways beyond schooling.

First: Fix the foundation and make schooling deliver employability. This requires ensuring that young people acquire the right mix of foundational skills (literacy and numeracy), higher-order cognitive skills (problem-solving and critical thinking), and technical and digital skills that the 21st-century labour market increasingly demands. The broad objective should be to end “schooling without learning” and halve learning poverty by 2030. Several steps follow.

Ensure quality early childhood education for all. This is critical to improve school readiness and raise learning outcomes throughout the schooling cycle.

Introduce entrepreneurship education in the school curriculum. Early exposure can help build a mindset for risk-taking, innovation, and initiative—encouraging young people to become job creators, not only job seekers.

Prioritise quality TVET at the secondary level. Increase participation in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) from the current meagre 1.2% toward a more ambitious medium-term target—such as 10% by 2030—on a credible path to 20% thereafter. This should be done in partnership with industry, with redesigned programmes aligned to high-growth sectors such as ICT, electronics, construction, and modern services.

Widen skills training in secondary education by empowering the Technical and Madrasah Education Division (TMED). This should accelerate the integration of practical skills into technical institutes and madrasahs, so employable skills complement religious education. More specifically, efforts should intensify to modernise madrasah education by integrating general subjects and vocational modules linked to recognised competency standards to enhance employability.

Build a robust school-to-work ecosystem. This includes early career counselling for school leavers, embedded soft-skills training (communication, teamwork, workplace behaviour), and greater emphasis on English plus one additional foreign language aligned to migration and trade opportunities.

Second: Expand skills pathways outside the formal education system and rethink national skills policy.

This is essential for young people who leave school early, those whose education left gaps, and workers who must upskill and reskill as labour-market demand shifts. Several reforms are urgent.

Revise the National Skills Development Policy to strengthen linkages between industry, education, and jobseekers—and to reduce fragmentation. Beyond harmonising key policies (Education Policy, Non-Formal Education Policy, Youth Policy, National Training Policy, and the NSDC Action Plan), the government should rationalise overlapping training programmes across the five segments of Bangladesh’s skills system (government, government-aided, private, NGO, and industry-based providers) and across institutions (polytechnics, Technical Schools and Colleges, BMET-TTCs, and madrasahs). Without rationalisation, resources will keep being spread thinly across too many programmes with too little measurable impact.

Implement structured on-the-job training and apprenticeship schemes. This requires upgrading existing frameworks so they deliver outcomes beyond paper—with employer participation, incentives, and traceable completion-to-employment pathways.

M Niaz Asadullah is Global Labor Organization (GLO) South Asia Lead, Convenor of Education Rights Parliament (ERP), and Head of the ICT White Paper 2025 Task Force for the Ministry of Post, Telecommunication and Information Technology.

Invest in skills for diversification beyond RMG. While garments remain vital, the future lies in higher-value diversification. Training programmes—both fresh skilling and reskilling—must build capabilities for agribusiness and agri-tech, light manufacturing upgrading, logistics, care work, and digital services linked to real demand and wage outcomes.

Strengthen pre-migration training in language, skills, and labour rights through BMET’s network of 110 TTCs and 6 Institutes of Marine Technology (IMTs). This will be critical for expanding overseas employment in non-traditional destinations and moving workers into higher-value, better-regulated pathways.

Increase the share and quality of longer diploma and certificate courses (six to twenty-four months), especially in non-RMG areas, within national TVET frameworks—while ensuring that course expansion is tied to placement rates, employer demand, and credible certification.

Lastly, strengthen capability and leadership in key institutions such as NSDA and BMET. Review the effectiveness of National Skills Certificates (NSC) and assessments, and expand training beyond “fresh skilling” to include upskilling, reskilling, entrepreneurship, apprenticeship, and Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL). The system must reward verified competence, not time spent in courses.

Rethinking Skills Beyond Schooling

Bangladesh’s July revolution has presented a once-in-a-generation chance to pivot away from youthwashing and toward genuine human capital development. The country cannot afford to lose the next decade as it lost the last 15 years. By prioritising youth in the policy agenda and implementing a two-track strategy—fixing education quality while expanding credible skills routes outside schooling—Bangladesh can turn its demographic dividend from a fleeting promise into a durable economic advantage, ensuring that young people become the driving force behind long-term prosperity.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments