18 months, few good films: Does July need historical distance to reflect on?

The July Uprising was when raw courage, anger, and hope collided on the streets. One can still picture Abu Sayed facing bullets with unwavering resolve—moments that make one’s chest tighten just thinking about them. The entire nation rose together, not just in protest, but in an extraordinary act of bravery that demanded to be remembered.

There are so many untold stories from July, yet when we look at our cinema, it gives the impression that the silver screen has barely scratched the surface of what July truly was. Are filmmakers hesitant to tell these stories? And why, in such a short period, have we only seen two July-related films make it to the theatres?

Ministry of Cultural Affairs Adviser Mostofa Sarwar Farooki shared his perspective on documenting the July Revolution.

“We are still too close to the real events. Right now, documentaries work much better than fiction. Fiction needs a little more time. Once there is some historical distance, filmmakers will be able to explore it more deeply and meaningfully”

The Ministry has been actively producing documentaries on July and its context, focusing on three key themes: the past covers 16 years of authoritarianism and the July Mass Uprising; the present celebrates an inclusive Bangladesh, highlighting ethnic diversity, cultural festivals, and traditional New Year celebrations; and the future looks toward a democratic Bangladesh. On the Chief Adviser’s Facebook page alone, these documentaries have racked up 118 million views, with millions more across other platforms.

Film critic Bidhan Rebeiro believes timing and perspective are key. “From what I have observed so far, this still needs more time. The events are still recent, and there is a sense of heat surrounding them. When someone works with that kind of heat, the time and mental space needed to dive deep are limited. What dominates instead is immediacy, and within that immediacy, there is a tendency for works to turn into propaganda films. Once this tendency fades, filmmakers can reflect more thoughtfully and create higher-quality works.”

Critic Sadia Khalid Reeti added that execution and intent matter just as much as timing. “Quality depends on who is assigned the work and with what intention. Many people have taken on July projects, but not all have the expertise. Some were rushed to align with the current government, and that urgency affected the depth of the films. Honest intent is essential. If someone is making a film only for funding, the quality suffers.” She also noted that many filmmakers might hesitate because the aspirations of July remain unfulfilled. “The hopes that people took to the streets for, the ideals they fought for, have largely not been realised. From that perspective, I understand why some filmmakers are reluctant to engage with the subject fully.”

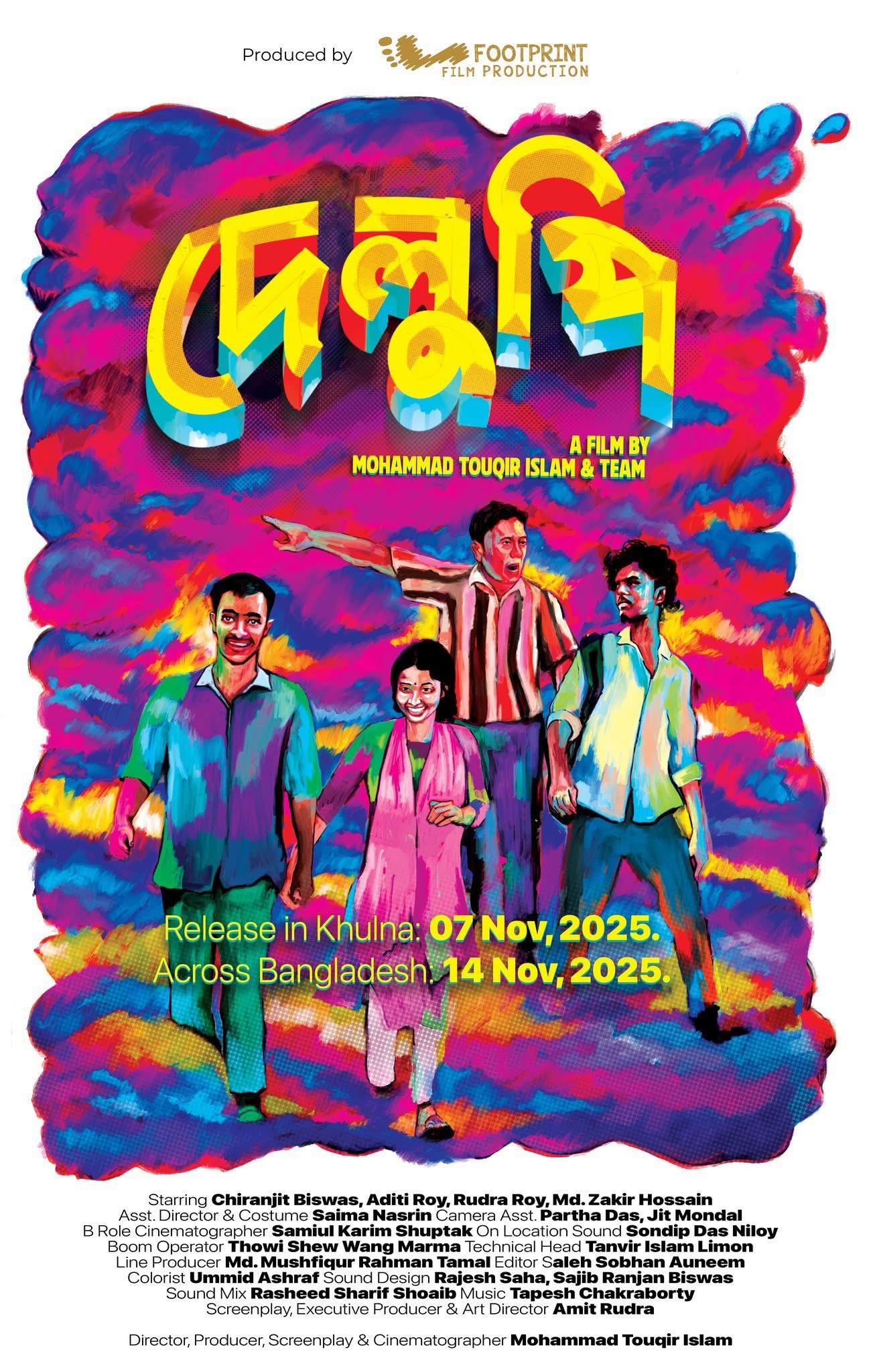

Director Mohammad Touqir Islam, who helmed “Delupi”, shared his approach:

“The time period my film deals with is very much the post-July phase. From July onward—basically immediately after the fall of the government—we are fictionally developing that period. The incidents we show are mostly events from the aftermath. We wanted to tell the story in a neutral way, without imposing a point of view”

"Since the film is set in a village, we aimed to show how people experienced July and its aftermath impartially.” He added, “Because the film is based on events from the immediate present, all our references were right there. That made it easier to select incidents and cross-check information. We tried to express the period as clearly and naturally as possible, without censorship," he added.

“Delupi” impressed with its symbolic approach, addressing July without explicitly naming it, making the story feel both universal and deeply relatable. The film struck a delicate balance between satire and optimism, particularly in its uplifting ending, though a deeper exploration of the political and social dynamics could have added more depth.

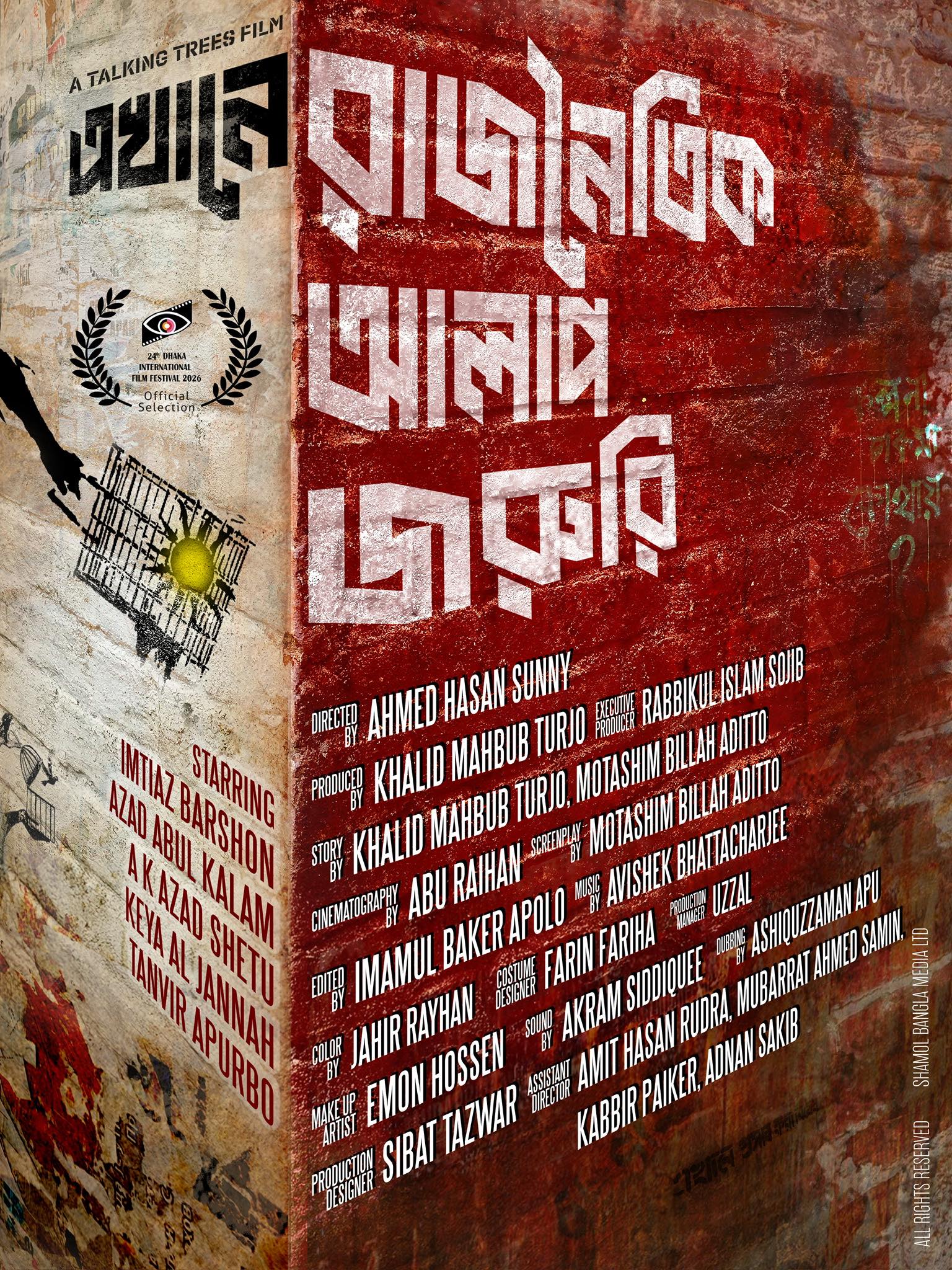

In contrast, “Ekhane Rajnotik Alap Joruri” took a bolder route, confronting July head-on. Its urgency and determination to tackle the political climate were evident, but the storytelling sometimes felt rough around the edges, and the political commentary lacked the subtlety that would give it a lasting impact.

On both films, Bidhan observed, “Even the films we are talking about—'Delupi’, for instance—display a certain kind of satire. I wouldn’t say they have a very deep political vision, but there is an immediacy in these films. They speak to the needs of the present moment. Regarding ‘Ekhane Rajnotik Alap Joruri’, it included July elements, but I feel it didn’t fully transcend the immediacy; it hasn’t yet become a film that will stand the test of time.”

Reeti shared a similar sentiment: “’Delupi’ felt very smart to me. Without explicitly calling July ‘July’, it symbolically addressed all the problems and demands we had. Especially the ending—it was so optimistic and positive. ‘Ekhane Rajnotik Alap Joruri’, released recently, felt bold in addressing July directly. But when I watched it, it seemed to lack the finesse.”

On the future of July-related films, both critics urge caution and thoughtfulness.

“Filmmakers must be careful not to turn films into propaganda. You can have your personal point of view, but imposing it on the audience diminishes the work. Quality will only come when films are approached honestly and thoughtfully”

“Whether more films are made depends on the political climate and the mindset of filmmakers. Post-election, there may be more room to explore July, but it has to be done with integrity, not just because funding is available”

In a place where history, politics, and creativity collide, the silver screen has barely touched the surface of July. Last year, the government announced funding for two feature films on the movement; whether they will actually get made, and whether they can truly capture the raw emotions of that time, only time will tell.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments