No ban, no boycott, still no World Cup

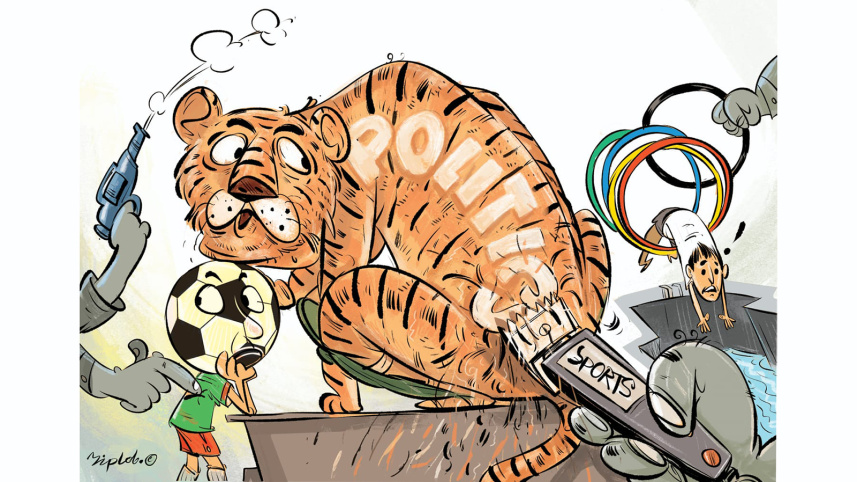

If international sports can be equated as pseudo-battles between two competing nations, mega sporting events like a World Cup or the Olympics can be thought of as an all-out war with honour at stake.

Unlike actual wars, where avoiding direct combat is often the most desirable outcome, in the symbolic battles of sport, absence brings shame, signalling a country’s failure to produce athletes who can compete with the world’s best.

In its 54 years of existence, Bangladesh have endured this ignominy repeatedly. It holds the unwanted record of being the country with the largest population to never win an Olympic medal, and it is far away from qualifying for the men’s football World Cup or the hockey World Cup. In fact, it hasn’t produced many athletes who can compete at the world level.

The sole exception to this culture of sheer mediocrity is cricket.

After trying for two decades, Bangladesh made its debut in the cricket World Cup in 1999. Including that maiden voyage in England, Bangladesh have so far competed in a total of 16 World Cups -- seven ODI World Cups and nine T20 World Cups -- in men’s senior cricket.

Although their trophy cabinet remains empty after 16 attempts and they are yet to go past the quarterfinal stage in the World Cup, through consistent appearances, Bangladesh has positioned itself as part of the upper echelon of cricket, a sport played in 110 countries.

They were set to do it once again in the 10th edition of the T20 World Cup in India and Sri Lanka, scheduled to begin on February 7.

But not anymore, as they were replaced by Scotland on January 24, after weeks-long failed negotiations between BCB and ICC about the relocation of Bangladesh’s matches from India amid security concerns.

This unexpected turn stemmed from an incident that set off the row, underscoring a trait common to both pseudo and real wars: the tendency to erupt from a single spark.

The spark

According to historians, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, on June 28, 1914, in Bosnia at the hands of a Serbian teenager started a domino effect that led to the First World War, one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history that claimed around 20 million lives.

The row between the BCB and the ICC was triggered by what the ICC later referred to as an “isoloated” and “unrelated” event, yet it ultimately pushed Bangladesh out of the T20 World Cup.

On January 3, the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) instructed Indian Premier League (IPL) franchise Kolkata Knight Riders to release Bangladesh pacer Mustafizur Rahman from their squad without specifying any reason, only saying it was done “due to the recent developments.”

The BCCI seemingly bowed its head to pressure from right-wing politicians and religious groups to remove Mustafizur without any cricketing cause, which was the foundation of Bangladesh’s claims of security concern.

The BCB, under the guidance of the government, reacted strongly, sending a letter to ICC the very next day to request relocation of tournament matches from India -- where the Tigers were supposed to play all four of their Group C matches.

What followed was weeks-long back-and-forth communications, differing speculations disseminated from online reports, and it eventually ended with both BCB and ICC staying unchanged in their respective positions.

ICC rejected Bangladesh’s request while the BCB, as per the government’s directive, said it can’t travel to India under the current circumstances, which led to ICC eventually naming Scotland in their stead.

Bangladesh’s exit from the T20 World Cup is unique in many ways. ICC never banned Bangladesh from competing, and neither the BCB nor the government ever said the Tigers don’t want to compete.

There was no ban from the ICC, nor a boycott from the BCB, still, Bangladesh are no longer in the World Cup.

The bans

Sports and geopolitics have long been intertwined, with wars often triggering exclusions from global competitions. The 1920 Antwerp Olympics, the first major event after the First World War, barred Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, Hungary and the Ottoman Empire for their roles in the conflict, with Germany excluded again in Paris. A similar pattern followed after the Second World War, when Germany and Japan were left out of the 1948 Olympics and the 1950 FIFA World Cup.

Wars have remained the most consistent cause for exclusion. Yugoslavia were banned from the 1992 Barcelona Games and the 1994 World Cup due to UN sanctions over the Balkan conflict, while Russia missed the 2022 World Cup and will sit out the 2026 edition over the Ukraine invasion. South Africa faced the longest ban, excluded from the Olympics, FIFA World Cup and international cricket from 1964 until the early 1990s due to apartheid. Afghanistan were barred from the 2002 Games under the Taliban, and Kuwait from the 2016 Rio Olympics over government interference, with their athletes competing as Independents -- a route also taken by Russian athletes in 2022.

The boycotts

Boycotts became a tool of collective protest, formalising the link between sport and politics. The 1956 Melbourne Olympics saw seven nations withdraw for political reasons: Egypt, Iraq and Lebanon over the Suez Crisis; the Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland against the Soviet invasion of Hungary; and China over Taiwan’s inclusion. The first high-profile football boycott came when Uruguay skipped the 1934 and 1938 World Cups in protest over limited South American participation in Europe.

Subsequent decades saw further political boycotts. In 1966, African nations stayed away from the World Cup in England over FIFA’s single qualification spot for Africa, Asia and Oceania. In 1976, 29 African countries boycotted the Montreal Olympics after the IOC declined to sanction New Zealand over its rugby tour of apartheid South Africa; 32 nations repeated the protest at the 1978 Edinburgh Commonwealth Games. The Cold War prompted the largest boycott in 1980, when over 60 countries, led by the US, skipped the Moscow Olympics; the Soviet bloc retaliated in 1984 with 15 countries missing Los Angeles.

In the 21st century, boycotts have largely become symbolic, with diplomatic withdrawals by the US, UK, Australia, Canada and others at the 2014 Sochi and 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics over Russia and China’s human rights records, while still allowing athletes to compete.

Bangladesh’s unique situation

Compared to other events, the cricket World Cup has been lucky in this regard, hardly ever facing a boycott nor has the ICC imposed any bans.

There have been instances when teams have refused to travel to a certain venue owing to security and other concerns during a World Cup.

It happened in the 1996 World Cup, when Australia and West Indies refused to go to Sri Lanka while in the 2003 edition, England and New Zealand refused to travel to Zimbabwe and Kenya, respectively.

In all these cases, the team that refused to travel had to forfeit that match.

When Australia cited it won’t send its team to Bangladesh for the Under-19 World Cup in 2016, they were promptly replaced.

However, when India did the same before the 2025 ICC Champions Trophy, refusing to travel to Pakistan owing to security risks and government orders, the ICC staged multiple tri-party communications and introduced a hybrid model, as part of which India and Pakistan won’t have to travel to the other country for any ICC event till 2027.

But when Bangladesh gave the same reasoning as India -- security concerns and government order -- they were strung along by the ICC for a few weeks before being outright rejected.

As said before, Bangladesh did not boycott nor were they banned from the upcoming T20 World Cup. The best way to describe their ousting, perhaps, would be term it a procedural exclusion.

Procedural exclusion

Till 2016, ICC had set a decent precedent. It had been firm when a country refused to travel to another country for a World Cup match, by either making them forfeit that game or by replacing them from the tournament.

Had the India incident not happened in 2024, the ICC could hardly be questioned for how it dealt with the Bangladesh case.

In its media release where it announced Bangladesh’s request has been rejected, one of ICC’s reasoning were that it did not want to set a bad precedent by accepting Bangladesh’s last-minute request.

But a poor precedent had already been set.

Yes, India had made their request months prior, before the tournament schedule had been announced. However, the schedule announcement was unusually delayed that year by the ICC, as if it had been expecting a rejection from the BCCI.

Furthermore, ICC had intentionally brought in PCB in the discussion as the hosts when India refused to travel. But in its discussions with the BCB, the BCCI was never involved, at least formally.

In that press release, the ICC referred to IPL as just “a domestic league,” but everyone knows that it is, in fact, the biggest money-making machine of the richest cricket board in the world, through which it exercises its power over world cricket and for which even the ICC has allotted an international cricket-free two-month window every year.

From the looks of it, ICC took its time to follow its written procedures, made sure it kept no loopholes and excluded Bangladesh from the tournament after the BCB refused to budge from its position.

The BCB, undoubtedly, made errors in the negotiations. The current board’s lack of diplomatic experience was evident as it has been reported that it failed to engage other boards in the issue, when it should have expected that the matter could go to a voting, as it did, where other than Pakistan the BCB found no support.

The aftermath

For Bangladesh, the die has been cast. The BCB reportedly faces a major earnings hit in the future and its relations with the ICC and the BCCI is expected to sour further.

The BCB is receiving some plaudits from home and beyond but when the financial strain begins, it would be interesting to see how the BCB manages the fallout.

For the ICC, the Bangladesh row is also not yet over. By refusing BCB’s security concerns and choosing to ignore how the BCB cannot go against its government’s directives, it has set a precedence of how to handle similar events in the future. Would it be able settle matters with an iron fist once again if the name of the team is India, Australia or England, instead of Bangladesh, it remains to be seen.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments