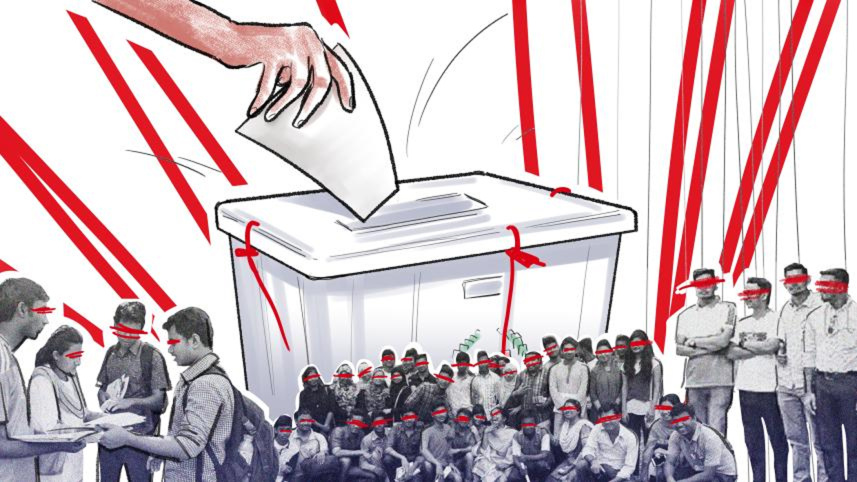

The electoral process has held so far. Can it withstand the final test?

Bangladesh’s long-awaited 13th parliamentary election is set to be held on Thursday. After the interim government took office in August 2024, it was unclear what an election leading to a real transfer of power would actually look like—whether it would happen at all, how credible it would be, and whether the process could hold together. Now, the atmosphere feels different. Not celebratory, not dramatic, but calmer, steadier, and more grounded than many expected.

What this election has not yet told us is, obviously, who will win, even though we all might have our predictions. What it has shown quite clearly, though, is that the process itself has held so far.

The mechanics have worked reasonably well. Nomination papers were duly filed, candidates were scrutinised, appeals were heard, and decisions—whether popular or not—were largely made within accepted legal frameworks. Election logistics also appear to be under control. Most importantly, the armed forces and security agencies have stood firmly behind the Election Commission to ensure that the vote goes ahead without disruption on February 12. In a country where elections have often unravelled long before election day, this matters.

The presence of foreign observers and a broadly positive diplomatic assessment helped reinforce confidence. After months of doubt and anxiety, the simple fact that Bangladesh is heading into a nationally competitive election at all is something worth acknowledging.

Party campaigning, too, felt different this time. For once, party manifestos have actually been discussed. Not just announced, but read, compared, and criticised. The conversation has moved—however unevenly—towards inflation, jobs, governance, and institutional reform. There has been less reliance on symbolism and far less negative emotional mobilisation than in past elections. Voters seem more interested in what parties claim they plan to do than in what they represent historically.

Negative campaigning hasn’t landed the way it once did. Attempts to brand rival parties and candidates with various labels do not appear to have shifted sentiment in any meaningful way. Economic stress and everyday frustrations seem to have crowded out the appetite for character attacks. Fear, as a political tool, has been noticeably weaker. Overall, the contest feels less like a knockout fight and more like shadow-boxing.

There’s plenty of positioning, tactical noise, and last-minute manoeuvring, of course, but very little sense of a single, defining national battle. Instead of a clean two-party clash, outcomes are likely to be decided seat-by-seat based on local candidates, ground organisation, and credibility within constituencies. Youth politics fits into this pattern as well.

Young voters make up a very large share of the electorate, many of them voting for the first time. Internet personalities and online activists played a decisive role during the mass uprising that brought down the Hasina regime—mobilising young people, sustaining momentum, and keeping pressure alive. But that influence has not translated easily into electoral power. The same voices have struggled to shape a unifying election narrative or meaningfully direct voting behaviour. The lesson is a familiar one. Social media is powerful at disruption, but elections still reward structure, local networks, and trust built on the ground.

Then there is the Awami League and the unspoken question of its supporters. Historically, the party commanded a large share of votes. Barred from participating and unable to articulate a coherent alternative strategy, the party has been totally absent in any form from the campaign. Sheikh Hasina’s calls to reject the election have circulated, but they have not visibly unified the rank and file. Instead of coordinated boycott or resistance, what we see is fragmentation. Some Awami League supporters appear inclined to sit this election out altogether. Others are quietly drifting towards alternative candidates at the local level. Many seem disengaged, uncertain, or simply waiting. Fear may explain part of this silence, but it does not explain all of it.

Awami League’s core ideological anchors—liberation identity and secularism—no longer function in the way they once did. Either those ideas have been rejected, or they are simply no longer decisive. This helps explain the broader realignment underway. Politics is becoming less about moral ownership of the past and more about competence, delivery, and future trajectory.

Voters, especially younger ones, are increasingly post-ideological. They are sceptical of the past political framework; they appear more realistic, mostly concerned about their transactional future, and willing to switch loyalties or disengage altogether. These patterns show that meeting the country’s needs—a credible process, issue-based scrutiny, limited impact of old attack narratives, restrained influence of social media, and constituency-driven and, above all, development-focused outcomes—is more significant than which party actually wins the election.

National identity does not change overnight. It evolves through repetition. Sustaining these electoral standards will eventually redefine Bangladesh’s political identity, proving that the people have learned to reclaim their power through the vote. And that, shall we hope, will be the most important and enduring change of all.

Sayeeful Islam is managing director of SSL, an IT company, former president of Dhaka Chamber of Commerce & Industry (DCCI), and former head of the think tank G9. He can be reached at sayeeful@gmail.com

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments