Can we afford such a steep public-sector pay hike?

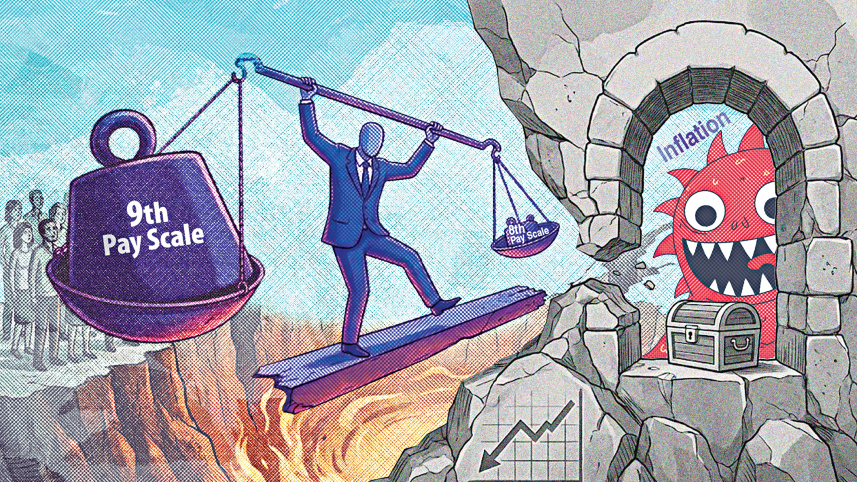

The Ninth National Pay Commission formed by the interim government recently recommended a salary increase for government employees in the range of 100-142 percent. While this increase is meant to bring huge relief to the government employees, policymakers must review a few important issues in this connection.

First, there is no denying that government employees have been hit hard by the inflation, persistently high for three years, as much as everyone else in Bangladesh. The last major revision that the government pay scale saw was in 2015; since then, the cost of living has risen sharply. A salary adjustment is, therefore, justified, but the scale and timing of the proposed increase require critical consideration. The proposed pay scale will cost the government an additional Tk 1.06 lakh crore every year. It is a major fiscal decision taken at a time when the country’s public finances are already heavily strained; the economy is under pressure due to rising debt, weak revenue collection, and growing expenditure obligations. The key question here is whether the government can afford this additional expense.

Second, where will the funds for increased salaries come from? Bangladesh’s current fiscal space is extremely limited. The tax-GDP ratio stood at only 6.8 percent in FY2025, one of the lowest in the world. Indeed, this ratio has been declining, indicating a weak domestic resource mobilisation capacity. During the first half of FY2026, the shortfall of revenue collection is Tk 46,000 crore. Given the National Board of Revenue’s (NBR) current capacity, it is highly unlikely that this gap can be closed by the end of the ongoing fiscal year.

Meanwhile, public expenditure pressures are increasing. The government continues to take bank loans, which is building its debt burden. As of November 2025, net credit to the government sector is Tk 5,53,910 crore, which is 26.28 percent higher than that in November 2024. External debt stands at $112 billion as of September 2025. State-owned enterprises, especially in the power sector, have accumulated huge unpaid bills. The Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB) has to pay about Tk 20,000 crore to private power companies. In addition, the government has to inject Tk 20,000 crore into the newly merged Islami Bank to improve its financial health. These commitments must be met.

Third, this pay scale increase will impact the composition of the national budget. A large share of Bangladesh’s budget already goes towards operational costs, such as salaries, allowances, and pensions of government employees. As this share increases further, the space for development spending shrinks. This has been the trend over the last few years, and it directly affects funding for health, education, social safety nets, skills development, science, technology, and innovation. These sectors are essential for improving productivity, reducing poverty, and preparing the country for future challenges.

Fourth, this salary hike also carries inflationary risks. When there is more cash in people’s hands, overall demand in the economy rises. In an economy with existing supply constraints, this can push prices even higher. Such an inflation will hurt people outside the government payroll, particularly private sector workers, informal workers, farmers, and small businesses. It will also undermine the central bank’s effort to curtail inflation through tight monetary policy.

Fifth, inequality is another major concern. While the government’s main objective should be to reduce inequality through various fiscal measures, such a salary revision will cause more inequality. Government employees will benefit directly from higher salaries, but most private sector workers will not. The private sector is already under pressure due to high borrowing costs, poor infrastructure, corruption, weak governance, and skill shortages. The government has been failing to improve these conditions. As a result, the gap between public and private sector incomes will likely widen further, exacerbating inequality in an already unequal society.

Sixth, whenever government salaries are raised, one familiar argument is repeated: higher pay will reduce corruption. Unfortunately, this argument does not hold up in reality. Corruption is not simply a result of low salaries; it is a structural and institutional problem. Bangladesh has revised government pay scales several times in the past, yet corruption has not declined. Government employees are paid from the taxpayers’ money; their duty is to provide services to the citizens of the country. Yet, in many cases, people are forced to pay bribes to receive even basic services. Evidence of corruption regularly emerges from various government departments and ministries.

To uproot corruption, institutions must be strengthened. Governance must improve. Rules must be enforced. Honest officials must be rewarded, and corrupt officials must be punished without political interference. Without accountability, higher salaries risk becoming an additional benefit on top of existing informal income from corruption, rather than a deterrence.

There is also a deeper issue of political economy at play. Successive governments appear reluctant to reform the civil service or hold powerful officials accountable. Politicians often seem wary of the bureaucracy. But government employees are meant to implement government policies, not operate above the policymakers. If the government truly believes in zero tolerance for corruption, that policy must apply to everyone.

The uncomfortable reality is that many political leaders themselves have benefited from weak governance and corrupt systems. This undermines the moral authority needed to enforce reforms. As a result, salary increases are often easier to implement than deeper, more difficult institutional changes.

The newly elected government following the February 12 national election will inherit this difficult situation. It will have to decide how to finance higher salaries while also meeting promises on social welfare, development, and economic stability. Under the current fiscal framework, it is extremely difficult to fully implement these salary increases without causing serious economic strain.

A more realistic approach would be to implement any salary revision gradually, in phases, linked to revenue performance and governance reforms. Lower-level employees may be paid first, given their economic circumstances. At the same time, urgent efforts are needed to strengthen tax administration, widen the tax net, improve public spending efficiency, and reform institutions. Without these steps, a large salary hike risks becoming a populist decision with long-term economic costs.

In the end, the debate is not about denying government employees a fair pay. It is about being fair to the entire population and responsible to the economy. Fiscal sustainability should be a key consideration in undertaking major fiscal decisions. Salary increase should be tied to broader economic conditions.

Dr Fahmida Khatun is an economist and executive director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). Views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments