The beleaguered financial sector and looming challenges

The money and financial markets build the bridge between the goods and services as well as the labor market. The financial sector is the crucial conduit for output and employment. This relationship is akin to how fuel energizes the engine to make the wheels rotate so the car can move. That is why any defect in the financial sector is enough to make other machinery of the economy dysfunctional.

Finance as the Engine of Growth

The health of the financial sector is the determinant of a country’s journey to development, vindicating the success stories of Singapore, Vietnam, Taiwan, and South Korea. They all emerged from agricultural feudal society, and their current state of excellence is the secret story of how they handled the act of finance from day one of their journey. Bangladesh’s success so far is attributable to how its financial industry developed. Its failures are also attributable to the practices of how politicians, businessmen, and bureaucrats corrupted the country’s financial institutions.

The decadence in the financial sector began in the 1980s when the military ruler president Ershad wanted to create a group of bourgeoisies who will support his regime. The best way to make it happen is to allow some degree of default loans to facilitate their business operations and political ambitions. Since then both regimes of Awami League (AL) and Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) continued that culture displaying an upward trend.

How Default Culture Took Root

However, it turned into a growing epidemic during the AL regime particularly after 2015 until the day they were overthrown in August 2024. The party changed characteristically under the dominant influence of business tycoons who earned a secret license to loot the banking sector in exchange for their unequivocal support for AL’s continuation of power. The interim government, though promised to revert the situation, got little success in the banking sector while the overall investment scenario has not emerged to vitality, making growth prospects weaker than before.

The capital market and the banking sector are the two wings of an economy. For Bangladesh, both wings are bruised. The reasons are twofold: 1) negligence of the capital market and lack of punishing its wrongdoers 2) the defective practice of holding the banking sector responsible for long-term financing. While banks are here for supporting short-term funds such as working capital or operational cash flow for industries, they were forced to fund long-term capital, making the role of the capital market redundant and creating the mismatch of maturity in fund management. This fundamental defect is at the root of why Bangladesh debauched both the stock market and banks.

When Both Wings of the Economy Failed

The toughest challenge is the act of reversing this practice and making it comparable to what we see in other emerging nations. Bangladesh’s financial sector is thus fundamentally flawed, and correcting this for good requires both knowledge and political intent. If politics is controlled by tycoons who are also engaged in tax dodging and money laundering, the oligarchs would never like to correct the practice since looting banks is easier than raising funds from the stock market where companies are vividly accountable to the shareholders by law.

Apart from this characteristic perversion in the culture of borrowing, the problems of Bangladesh’s financial sector are deep rooted mainly because of its courtship with politicians. When politicians chase businessmen for rent seeking, that is one kind of problem which creates extortive ambience. But the problem is worse when businessmen turn into politicians and distort financial rules in their favour. This gambling ensures malfunctioning of the financial industry by launching perverse politics. The AL regime made the biggest blunder by empowering a group of businessmen who twisted financial law in their favour to normalize their plunder and laundering. Stock-market scammers and bank looters were made the guardians of the sector.

The July-August uprising of 2024 created a glimmer of hope, and we expected to see the end of the businessmen-led politics and bureaucratic tangles. A lot was spoken about financial reform while little might have been achieved without touching the main flaws of the financial world. The White Paper report was intended to get the future guidelines, and the Economic Task Force report was aimed at taking steps toward a healthy economic order and fiscal empowerment. The interim regime, however, failed to produce a coherent set of economic laws which would govern the financial industry to reduce default loans and illicit financial transfers.

Illustration: E. Raza Ronny

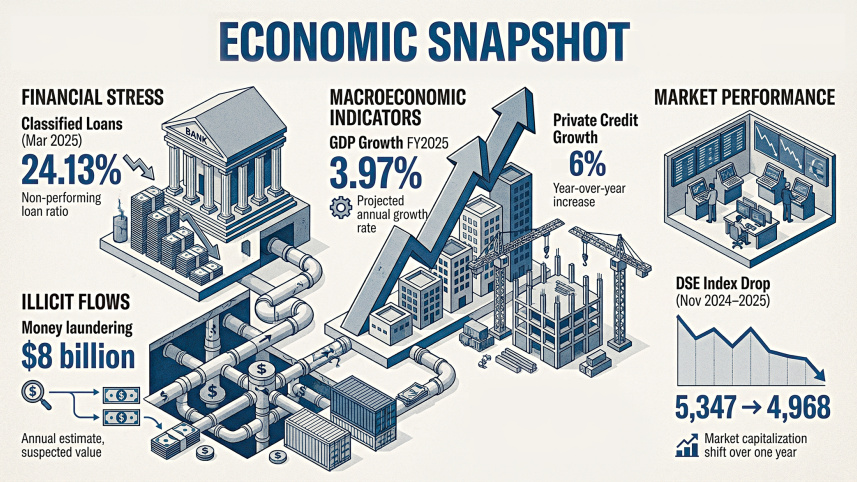

Default loans kept rising without any sign of abating. The amount of classified loans occupied 16.93 percent of total outstanding loans in September 2024, rising to 24.13 percent in March 2025. Recently, the central bank has resorted to using the sugar-coated definition of default loans, which will simply put the dirt under the carpet temporarily without delivering any viable solution. Global Financial Integrity estimates the annual figure of money laundering as around 8 billion dollars, with no evidence that this figure has gone down since the interim government took office.

A System Locked in Political Finance

Politicization of the business world is at the root of the growing disease of nonperforming loans. Since ill-gotten money is not safe to keep inside the country, money laundering becomes inevitable. Rising default loans also enable tax dodging as most oligarchs take the opportunity to show losses beforehand and are thus waived from paying taxes. This creates a second impulse for illicit financial transfers. The financial industry is trapped in the devils’ triangle with loan defaulters, tax dodgers, and money launderers, and the interim government is still far away from breaking it.

While empowering the central bank with autonomy is a step forward, that reform alone is not enough to rescue the beleaguered financial sector from decadence and perversion. Reforming the capital market first is the way to push long-term borrowers toward that market, allowing banks to focus on short-term working capital and some startup loans to agriculture and small enterprises. The Dhaka Stock Exchange Index was 5,347 in early November 2024 but fell to 4,968 around the same time one year later, suggesting growing debility in the stock market despite the interim government’s six-point revitalization strategy.

Stabilisation Without Reform

Although unemployment is a concern for the labor market, addressing joblessness is impossible without financial stability that enables private investment and employment generation. Domestic private investment is not only in the doldrums but dwindling, while foreign investment remains below one percent of GDP and private investment stands at around 22 percent.

Low inflation—the precondition for financial stability—remains elusive. Its 12-month average stood at 9.95 percent in August 2024 and was still 9.22 percent in October 2025, despite promises to bring it down to 6 percent by June 2025. The call money rate has remained close to 10 percent since June 2024, keeping borrowing costs prohibitively high.

With GDP growth falling to 3.97 percent in FY2025, the overall rate of return in the business sector has likely dropped below 10 percent. Borrowing for business thus becomes unwise unless default is premeditated. Private credit growth has accordingly fallen to around 6 percent, far below the 15 percent needed to support real growth.

The declining trend in reserves has been reverted and that gives credit to central bank policy of the market-based exchange rate but import contraction has played the main role in reserves’ buildup. This contraction has been as high as 9 percent for intermediate goods and 25 percent for capital machinery for FY2025, partly hinting at why GDP growth has come to the lowest point in the post-Covid era.

A fair, inclusive, and acceptable election is expected to boost private investment via market confidence, but other tangles of the financial world such high default loans, tax dodging, money laundering, and the capital market irregularities will persist, requiring a fresh batch of reforms by the elected government in 2026.

Dr Birupaksha Paul is a professor of economics at the State University of New York at Cortland, USA. His book is Bangladesher Orthonitir Songskar (Reforms for the Bangladesh Economy).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments