Rethinking social protection in Bangladesh: What role can active labour market policies play?

Bangladesh’s social protection system has a long history of experimentation and has played a meaningful role in reducing poverty since the early 1990s. Bangladesh allocates around 15 percent of its national budget—about 2 percent of GDP—to social security, spread across nearly 95 programmes. In recent years, revisions and reviews of key programmes have helped consolidate the social security system and improve coherence. Yet the system largely evolved in a fragmented and relief-oriented manner, responding to immediate vulnerabilities rather than anticipating longer-term structural changes in the economy—leaving important gaps unaddressed.

These gaps have become increasingly evident due to the social protection system’s limited responsiveness to emerging labour market and socio-economic dynamics. The existing social protection architecture remains weakly aligned with labour market dynamics and ill-equipped to address emerging challenges such as rising unemployment, pervasive informality, and persistent skill mismatches. Labour-market-focused interventions remain marginal within the broader system: only BDT 4,171 crore—just 3.57 percent of total social protection spending—is allocated to 19 labour market programmes. This imbalance limits the system’s ability to support productive employment and smooth transitions in an increasingly competitive and changing labour market.

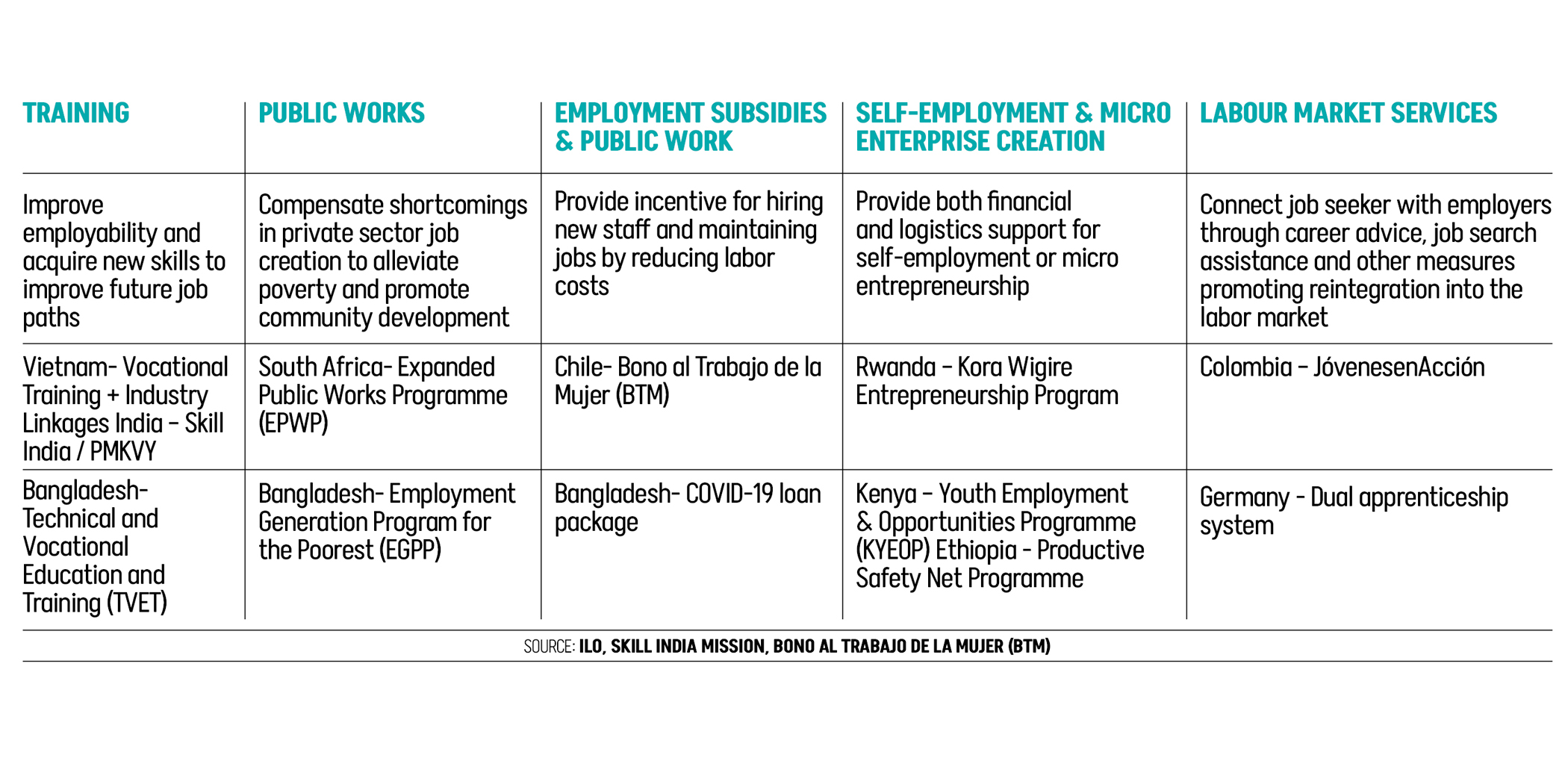

Against this backdrop of mounting labour market pressures, active labour market policies (ALMPs) have gained renewed relevance. ALMPs are targeted interventions aimed at improving employability, strengthening job matching, and facilitating entry into productive work. The International Labour Organisation classifies ALMPs into five broad categories: skills training, public works, employment subsidies, self-employment support, and labour market services (Table 1). Their importance is underscored by recent labour market trends. The Labour Force Survey 2024 shows that national unemployment has risen to 3.66 percent, while graduate unemployment stands at an alarming 13.5 percent—more than double its level eight years ago. Youth unemployment has increased to 8.07 percent, and the number of young people not in education, employment, or training (NEET) has grown to 8.56 million, signalling a gradual erosion of Bangladesh’s demographic dividend.

In response to growing labour market pressures, a range of active labour market interventions are already being implemented through government agencies. Public works programmes—most notably the Employment Generation Programme for the Poorest—provide short-term employment during lean agricultural seasons while supporting small-scale community infrastructure. Technical and vocational training is also provided for different age groups, including short courses ranging from one to five days. While Bangladesh does not yet operate formal wage subsidies or job retention schemes, the COVID-19 crisis offered an important policy lesson: the government’s temporary BDT 5,000 crore loan package for export-oriented industries helped preserve jobs during an acute shock. Replicating such wage support in the post-COVID period, however, has proven difficult amid tightening fiscal space.

A key challenge confronting these labour market programmes is that they largely operate in silos, remain weakly connected to industry demand, and prioritise enrolment numbers over employment outcomes. As a result, many interventions fall short of improving long-term employability or helping workers transition into better-quality jobs in a changing economy.

These shortcomings point to a broader opportunity: rather than treating employment support as a peripheral add-on, active labour market policies need to be embedded more systematically within social protection—so that programmes not only cushion households against shocks, but also help people move into sustained and productive work.

International experiences offer helpful policy lessons. Countries across various income levels have used active labour market policies to reshape employment outcomes when supported by strong institutional coordination and close engagement with the private sector. Vietnam offers a particularly relevant example. By expanding vocational training centres, forging partnerships with global firms such as Samsung and LG, and targeting rural youth with industry-relevant skills, Vietnam facilitated large-scale movement from low-productivity agriculture into manufacturing. These reforms helped lay the foundation for Vietnam’s emergence as a dynamic manufacturing hub—demonstrating how well-designed ALMPs can actively drive structural transformation, rather than merely manage its social costs.

Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme goes beyond food security by combining public works with skills training, savings support, and small business grants, helping vulnerable households build resilience against shocks such as droughts. Rwanda’s Kora Wigire Entrepreneurship Programme has similarly enabled thousands of young people—especially women—to start small enterprises through training, access to finance, and basic toolkits.

Latin America provides further evidence of targeted approaches. Chile’s Women’s Employment Subsidy offers cash incentives to low-income women, contributing to modest but measurable gains in formal employment. Colombia’s Youth in Action programme combines training, stipends, life skills, and internships, leading to higher employment rates among disadvantaged youth. Comparable initiatives in Kenya and South Africa show that well-designed public works and youth employment programmes can improve employability when linked to skills development and labour market demand.

Advanced economies demonstrate the long-term payoffs of sustained investment in labour market institutions. Denmark’s “flexicurity” model—combining flexible hiring with strong income support and active job-search assistance—has kept unemployment low and re-employment rapid. Germany’s dual apprenticeship system, which integrates classroom learning with workplace training, has ensured smooth school-to-work transitions and consistently low youth unemployment. These examples underline a common principle: labour market policies work best when training, income support, and employer engagement are tightly coordinated.

For Bangladesh, the message is clear. Effective active labour market policies are coherent, demand-driven, and targeted. Training must be aligned with industry needs; internships and apprenticeships should be expanded; and vulnerable groups—particularly poor youth, women, and informal workers—must be prioritised.

Rather than expanding programmes indiscriminately, policymakers should focus on consolidating fragmented labour market programmes, strengthening labour market information systems, scaling up industry-linked training and apprenticeships, and piloting targeted wage or hiring incentives within clear fiscal limits. Embedding these reforms within the social protection system would allow Bangladesh not only to protect workers from shocks, but also to equip them for productive employment—turning social protection into a driver of inclusion, productivity, and long-term economic resilience.

Dr M Abu Eusuf is professor of Economics at the Department of Development Studies andthe executive director of Research and Policy Integration for Development (RAPID). He is alsofounderdirector of the Centre on Budget and Policy at the University of Dhaka. He can be reached at eusuf101@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments