No growth without planned urbanisation

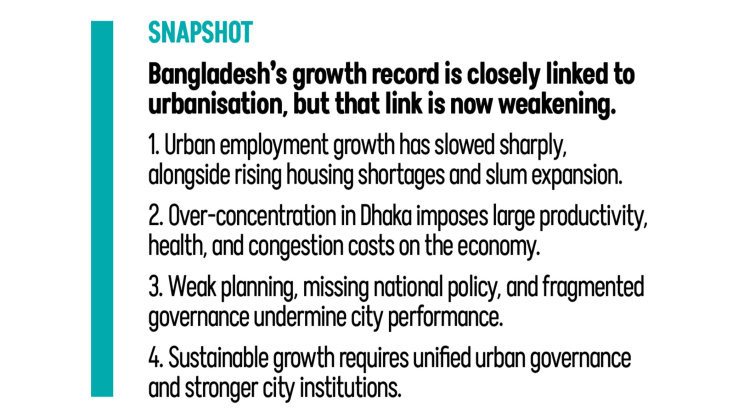

After remarkable progress and growth, especially under elected governments from 1991 to 2015, Bangladesh now faces numerous challenges. Political and macroeconomic instability; troubled public finances and banking systems; poor-quality education and health services; an undiversified economy, stalling private investment, and rising joblessness. These problems all intersect at one location: our failing towns and cities.

Without well-planned urbanisation, there can be no long-term growth and development in Bangladesh. Globally, urban areas cover only about 3 per cent of land but account for 80 per cent of economic activity. No country has achieved long-term economic growth without urban development. Bangladesh’s history fits international experience. As urbanisation increased fourfold since independence, per capita incomes grew fivefold.

Dr Ahmad Ahsan is Director, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh. The views expressed here are his own. This column draws on several of his research papers. He can be reached at ahmad.ahsan@caa.columbia.edu.

However, urbanisation alone is not enough. Many countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America have urbanised without growth. If urban development is unplanned and unable to attract investment that creates more productive jobs, or to provide transport, education, health, sanitation, and housing, then urbanisation will occur without industrialisation and growth.

Signs of a failing urban transition

Bangladesh now faces that prospect. The urban economy’s troubles are reflected in the sharp slowdown in urban employment growth to 0.8 per cent per year over 2017-22, compared with 4 per cent in the previous period (2010-17), and in the movement of most industry to rural areas in the 2010s.The housing deficit is estimated to have exceeded 8million units in 2021. That, along with the sharp rise in land prices, has forced half of the urban population to live in slums. Unsurprisingly, key health and education indicators are worse in urban areas than in rural areas in about half of Bangladesh’s districts.

Consistent with these trends, the 2022 Census indicates that urbanisation in Bangladesh is stalling, particularly in larger cities and towns. Thus, 10 city corporations show a marked slowdown in population growth over the last decade. Two, Mymensingh and Rangpur, are exceptions only because their areas have been increased by four times or more. Overall, the BBS now estimates the urban population share at 32 per cent, substantially lower than the 40 per cent projected by UN DESA. It is worth stressing that the recent UN report designating Dhaka as the second-largest city in the world, with 36 million inhabitants, is problematic because its Eurocentric definitions are inappropriate for densely populated Asian countries. But, even so, the spirit of the message of an excessively overpopulated Dhaka is correct.

Three structural barriers to planned urban growth

This brings us to the first of the three specific challenges that impede the well-planned urbanisation of Bangladesh.

First, about 33 per cent of the urban population is concentrated in the primary region of greater Dhaka and its environs, well above the 23-25 per cent research suggests would be the optimum share. Dhaka’s overgrowth by about 60 per cent (my research) above the optimum size results in high costs of excessive size: time loss and energy costs associated with extremely long commutes and traffic congestion. These also lead to increased morbidity from pollution and to economic costs of reduced productivity. Then there is the cost of diverting resources away from other cities and towns where productivity would be higher. Taken together, Dhaka’s overgrowth costs Bangladesh about 6-10 per cent of GDP, a substantial figure.

Second, unfortunately, while the 2022 Census presents a welcome redistribution of urban population share away from Dhaka district, to the neighbouring districts of Gazipur and Cumilla-Chattogram corridor, most of the redistribution has been to the smaller towns as opposed tos econdary cities and towns. These are relatively less populated than the top three most urbanised districts and the less populated districts and towns. These trends, also confirmed by nightlight density measurements and industry moving to rural areas, suggest that Bangladesh may be losing the benefits ofeconomic agglomeration and scale. As evidence, we find that the positive economic impact of urban development on household consumption and wages mainly arises from the three most urbanized districts of Dhaka, Chattogram, and Gazipur. Excluding these, urban development has no positive impact.

The third challenge isa glaring hole in our national policies regarding urban development. That has three aspects. A. There is no national urban development policy framework. B. Urban planning is extremely weak and, in practice, mostly ignored. C. Urban governance is highly fragmented, with limited local-level accountability and weak city-municipality governments.

Governance, planning failures, and the path forward

First, unlike China, India, Indonesia, Vietnam, and other major developing countries, Bangladesh does not yet have a national urban policy. The National Urban Policy Draft was prepared following extensive consultations over several years and presented to the Cabinet in 2013, but remained unapproved. While Five-year plans dedicate a section to urban development, they are essentially statements of intent and laudable goals. They do not identify policies and instruments to implement these goals.

Related to this is the virtual absence of planning. By definition, urban development is replete with “market failures” caused by large-scale investment requirements and the presence of “externalities” arising from population and economic density: i.e., actions of individuals and firms - e.g., those that create waste and pollution - affect not only themselves but also their neighbors, neighborhoods, and the whole city. Then “complementarities”create coordination problems: factories and jobs, marketplaces, transport and power, water and sanitation facilities, housing, schools, hospitals, parks, and other amenities must be provided together. Hence, sound planning is essential for the provision, valuation, allocation, and zoning of serviced land, as well as financing for all these activities.

The failure of our planning is evident from the histories of the Dhaka and Chittagong municipalities. While both were incorporated in the 1860s, Dhaka is the only city that has a centralized – though still partial - sewerage system. In Chattogram, wastewater is discharged into septic tanks and subsequently channeled untreated into water bodies, rivers, and the Bay of Bengal. Similarly, only a minuscule fraction of the 2,289 tons of solid waste generated in Chittagong is recycled.

Even when plans are prepared, implementation can fail spectacularly, as evidenced by the construction of an underutilized expressway over the main CDA Avenue, which expressly violates the Chattogram Master Plan and ruins the city’s main avenue. The view outside the main cities is, predictably, dismal. According to the LGRD data, while two other cities and 256 Paurasabha/Municipality Master Plans had been prepared, only five had been gazetted. These five twenty-year plans, covering 2011-2031, were approved 5 to 7 years after preparation, essentially dead on arrival. Not surprisingly, cities and towns are starved of public spaces and playing grounds far below the recommendations of the WHO.

Finally, there is the matter of fragmented governance in cities and towns, as well as weak city and municipal governments. The problem starts from the top. Again, unlike in most other advanced and developing countries, urban development responsibility is not vested in a single ministry but in two: Housing and Public Works and the LGRD. Management of roads, water, housing, health and sanitation, and public works lacks coordination at the top. In addition, there are other agencies, such as the Electricity Supply Authority, the Roads and Highways Ministry of Road Transport and Bridges, and the Ministries of Health and Education, that operate under vertical supervision without local coordination in cities and towns. Finally, not least, the Ministry of Land also has a say regarding land acquisition.

City corporations’ governance is fragmented into three parts: the Mayor’s office, the city development authority, and the city and district administrative authorities. In the case of the smaller city corporations, the situation is the same, except that there are no development authorities. In principle, there is a coordination committee chaired by the Mayor. However, in practice, the development authority and Deputy Commissioner’s offices send low-level representatives to the committee and largely ignore it. The Deputy Commissioner is nominally responsible for coordinating the vertically directed activities of more than 40 line ministries and government agencies.

Unsurprisingly, chaos rules in building construction, traffic and transportation, water supply, and drainage. Sustainable growth and employment supporting urban development cannot take place under these conditions.

The solution lies in unifying urban governance and planning under the office of the Mayor of cities and municipalities, who are accountable to the people, elected by them. At present, their budgets and their technical capacity are minuscule. The best estimate for the 12 city corporations is that their budgets are about 0.7 per cent of their GDP, compared with 6 per cent in Delhi and about 10 per cent in Ho Chi Minh City. However, one will also need to provide technical and financial management capacity to city governments in a coordinated manner under a single Ministry. Finally, the performance of city and municipal governments must be transparently monitored by both the Central Government and citizens’ organizations.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments