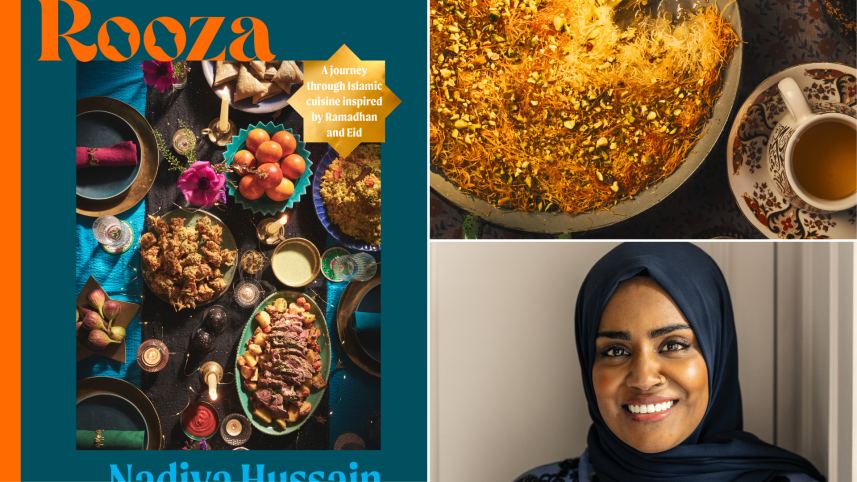

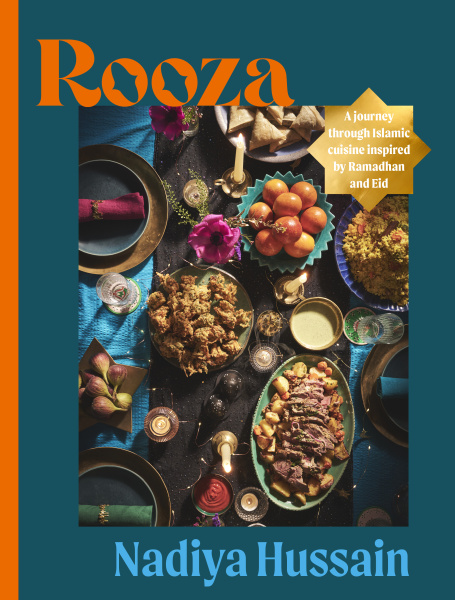

Rooza Shows why Bangladeshi food belongs on every Ramadan table

For much of the world, Nadiya Hussain is a household name. She’s the winner of The Great British Bake Off, a bestselling author, television presenter, and the familiar face of modern British home cooking. However, in Rooza, her last cookbook, Hussain turns away from the polished studio kitchen and towards something deeper and more personal. This is a book shaped by Ramadan nights, by fasting and feasting, by family tables heavy with anticipation, and by a quiet and subtle reclaiming of her Sylheti and Bangladeshi roots.

As she once told me in an interview, “As a child of immigrants, I never understood the importance of the food my grandparents and parents left behind. It was a reminder of home for them, and for us, it is the food that connects us to our heritage.”

The very title signals this return. “Ramadan” is the word recognised globally, but in many South Asian Muslim homes, including Hussain’s, the month was always called Rooza — a word that translates simply as “fasting”. In the opening pages, Hussain writes with gentle insistence: to me, Rooza it shall always be. That statement is more than linguistic nostalgia. It is an assertion of cultural memory, a refusal to smooth out difference for the sake of universality.

Born in Luton to parents from Sylhet, Bangladesh, Hussain grew up observing Ramadan in a way that was intimate and domestic, contained within family and community. Long before supermarkets stocked “Ramadan aisles” or shop windows declared “Ramadan Mubarak”, Rooza unfolded quietly in kitchens like hers. Days were shaped by restraint and fasting; evenings by care, planning and generosity. In Rooza, Hussain captures this rhythm beautifully, describing Ramadan as an old friend — one who returns every year exactly when you need them most.

Food, in this context, is not a spectacle. It is sustenance, reward, and love. As Hussain reminds us, after a day without food or water, what is placed on the table at sunset matters enormously. Iftar is the one meal that gathers everyone, no excuses, no delays. In her home, and in this book, it must be nourishing, filling, and deeply satisfying.

What makes Rooza a departure from Hussain’s earlier work is its scope and confidence. Structured as a journey through Islamic cuisines across the world, from Turkey and Tunisia to Somalia, Malaysia, Iraq, Bengal and beyond, the book presents thirty complete Ramadan meals, followed by an expansive Eid-ul-Fitr section. Yet, threaded through this global tour is a steady emotional pull towards South Asia, and particularly Bengal.

Bangladesh appears not as an afterthought but as part of a continuum, as one node in a vast Muslim culinary map. There is an ease with which Hussain moves between geographies, reflecting how Muslim food cultures have always travelled: through trade, migration, prayer and memory. For Bangladeshi readers, this feels quietly affirming. Our food is not niche; it belongs naturally within a global Islamic table.

At the same time, Rooza is unmistakably maternal. Dedicated to mothers: “the table would not be what it is without you, “the book honours the invisible labour of women who cook while fasting themselves, who plan, who feed everyone else first. Hussain writes not as a celebrity chef but as the head of her household kitchen, balancing worship, work, exhaustion and care. This perspective resonates strongly across South Asian Muslim homes, where Ramadan is often carried on the backs of women.

There is also joy here, real, generous joy. Hussain delights in discovering new cuisines during Ramadan, in breaking the monotony of familiar dishes with curiosity and play. A Turkish shish, an Iraqi kibbeh, a Somali suqaar or an Algerian pancake are not presented as exotic novelties, but as respectful homages, cooked with enthusiasm and decorum. Ramadan, in her telling, is not about deprivation alone; it is about the abundance of spirit.

For a Bangladeshi audience, Rooza lands with particular warmth because it reflects a shared emotional vocabulary. The idea of Ramadan as the one month when family dinners are guaranteed, when children appear on time, when voices soften, and generosity sharpens—these are universal experiences across Muslim households, whether in Sylhet, Dhaka, or Luton.

In reclaiming the word Rooza, Hussain also reclaims a way of being Muslim that is layered and plural. She does not flatten faith into a single narrative, nor does she exoticise it for a non-Muslim gaze. Instead, she invites readers, Muslim and otherwise, into her lived experience, one meal at a time.

As Eid approaches at the end of the book, the tone shifts to celebration and sweetness. Yet, even here, the message remains rooted: food brings people back to the table, year after year. Children may grow up and move away, but the memory of these meals, of Rooza, will call them home.

With Rooza, Nadiya Hussain does something quietly radical. She steps back from the centre of British food celebrity and stands firmly within a global Muslim kitchen, one that includes Bangladesh not as an origin story footnote, but as a living, breathing presence. For readers observing Ramadan this year, her book offers not just recipes, but recognition. And that may be its greatest gift.

Photo: Chris Terry

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments