Why Bangladesh's veterinarians matter more than we think

Bangladesh's public health story is often told through the lens of hospitals, epidemics, and human suffering. We speak of dengue seasons that stretch longer each year, of malnutrition that continues to shadow childhoods, of climate‑driven diseases creeping into new districts. Yet beneath these visible crises lies another, quieter struggle; one that begins not in hospital wards but in farms, fish ponds, live bird markets, and the countless households where humans and animals share space, water, and risk. This struggle determines whether the food on our plates is safe, whether our health system can withstand the next outbreak, and whether life-saving medicines will remain effective for our children. It is shaped by a group of professionals whose work rarely makes headlines: Bangladesh's veterinarians.

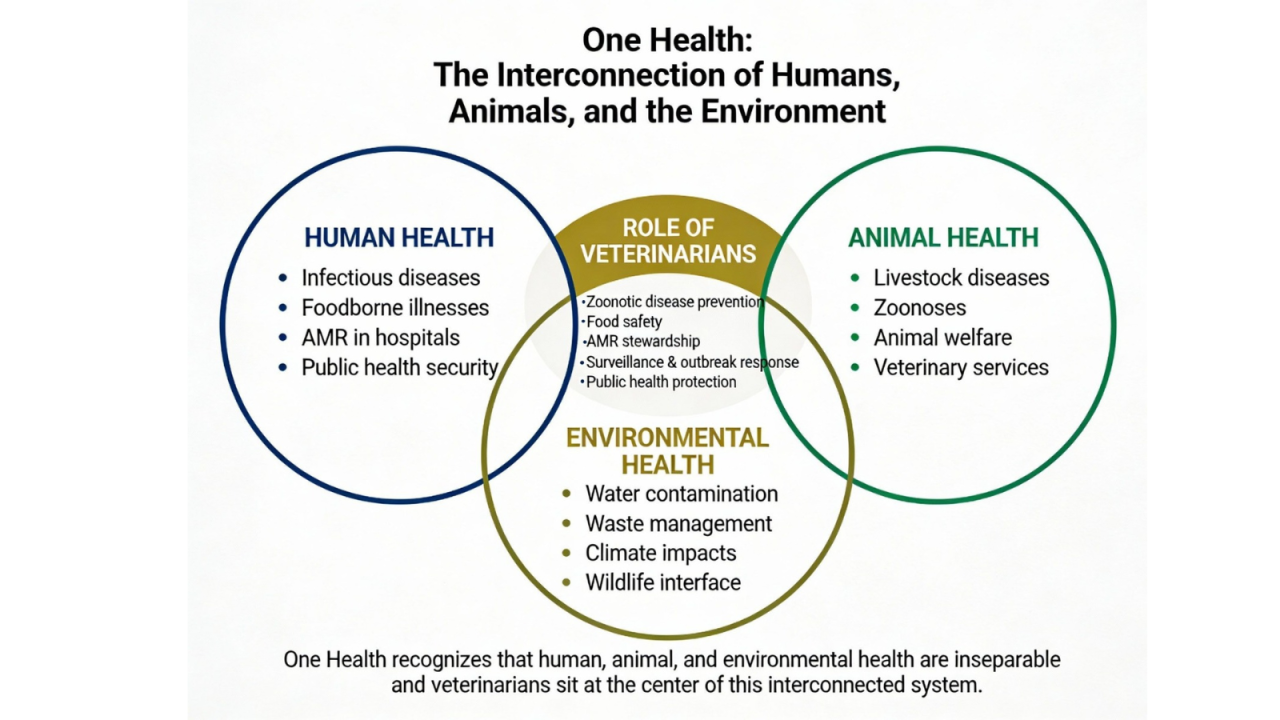

The role of Bangladesh's vets is not limited to treating sick cows, poultry, or pets. They stand at the intersection of human, animal, and environmental health -- an intersection that global experts now call "One Health." In a country where people live in close and constant contact with domestic and peridomestic animals, where zoonoses and multidrug‑resistant organisms are increasingly reported, veterinarians are not peripheral actors; they are central to national health security. Yet their contributions remain largely invisible. Their shortages are rarely discussed, their challenges seldom reach the policy agenda, and their potential, which is immense, transformative, and urgently needed, remains under-used.

To understand why this matters, and why Bangladesh must rethink its approach to animal health, we must confront the realities of our interconnected vulnerabilities and learn from how other Asian countries have strengthened their veterinary public health systems.

A typical day of a government veterinarian might begin with an emergency call from a poultry farm where mortality has suddenly spiked. The veterinarian examines the birds, collects samples, and advises immediate biosecurity measures. He suspects a viral disease, perhaps avian influenza or Newcastle disease; but laboratory confirmation will take time, and the nearest adequately equipped lab is far away. Meanwhile, he must calm the farmer, reassure workers, and quietly worry about whether the birds have already been sold into nearby markets.

A nation built on interdependence

Bangladesh's food system is vast, intricate, and deeply interdependent. Livestock and aquaculture are not just economic sectors; they are woven into the fabric of rural life. Chickens in courtyards, goats tied near kitchens, cattle in backyard sheds, fish ponds at the edge of homesteads; these are daily companions, sources of protein, savings accounts on four legs, and buffers against crisis. This intimacy brings benefits, but it also brings risk.

When animals fall sick, the consequences ripple far beyond the farm. A contaminated batch of milk can affect hundreds of families. A poultry outbreak can wipe out a farmer's flock and seed infection in humans. An anthrax‑infected carcass, slaughtered and consumed out of desperation, can trigger a cluster of human cases. A dog bite, if not followed by timely vaccination and proper wound care, can still mean a death sentence from rabies.

These are not hypothetical scenarios. Bangladesh has faced repeated episodes of anthrax in livestock with spillover into humans, waves of avian influenza, and persistent rabies risks. A national One Health zoonotic disease prioritisation exercise identified high‑priority zoonoses; including anthrax, rabies, Nipah virus, zoonotic influenza, brucellosis, and zoonotic tuberculosis; that require coordinated, multisectoral action. That action depends heavily on the presence, skills, and authority of veterinarians.

Geography and demography amplify these risks. High population density means humans and animals share space more intensely than in many parts of the world. Climatic extremes like floods, cyclones, and heatwaves disrupt ecosystems and stress both people and livestock. Floodwater spreads animal waste and pathogens into drinking sources, while salinity intrusion alters disease patterns in coastal aquaculture. Urbanisation creates new interfaces -- stray dogs around garbage dumps, free‑roaming poultry near markets, backyard livestock in expanding townships.

Weak veterinary coverage does not stay confined to animal health. It eventually appears in human case records, in hospital microbiology reports, and in the spread of resistant bacteria that no longer respond to standard treatments.

This is precisely the context in which a One Health approach becomes more than a slogan. Organisations like One Health Bangladesh now explicitly recognise the need to unite human, animal, and environmental health for a safer Bangladesh. However, the day‑to‑day reality of One Health comes down to people on the ground: often an overworked veterinarian with a motorcycle, a stethoscope, and a phone that never stops ringing.

The veterinary frontline: essential, overstretched, and undervalued

Imagine a government veterinarian posted to a peri‑urban upazila. On paper, his responsibilities include clinical care for livestock and pets, vaccination campaigns, outbreak investigation, meat inspection, reporting to district authorities, and advising farmers on feeding, breeding, and disease prevention. In practice, he may be one of only a handful of veterinarians serving tens of thousands of animals.

A typical day might begin with an emergency call from a poultry farm where mortality has suddenly spiked. The veterinarian examines the birds, collects samples, and advises immediate biosecurity measures. He suspects a viral disease, perhaps avian influenza or Newcastle disease; but laboratory confirmation will take time, and the nearest adequately equipped lab is far away. Meanwhile, he must calm the farmer, reassure workers, and quietly worry about whether the birds have already been sold into nearby markets.

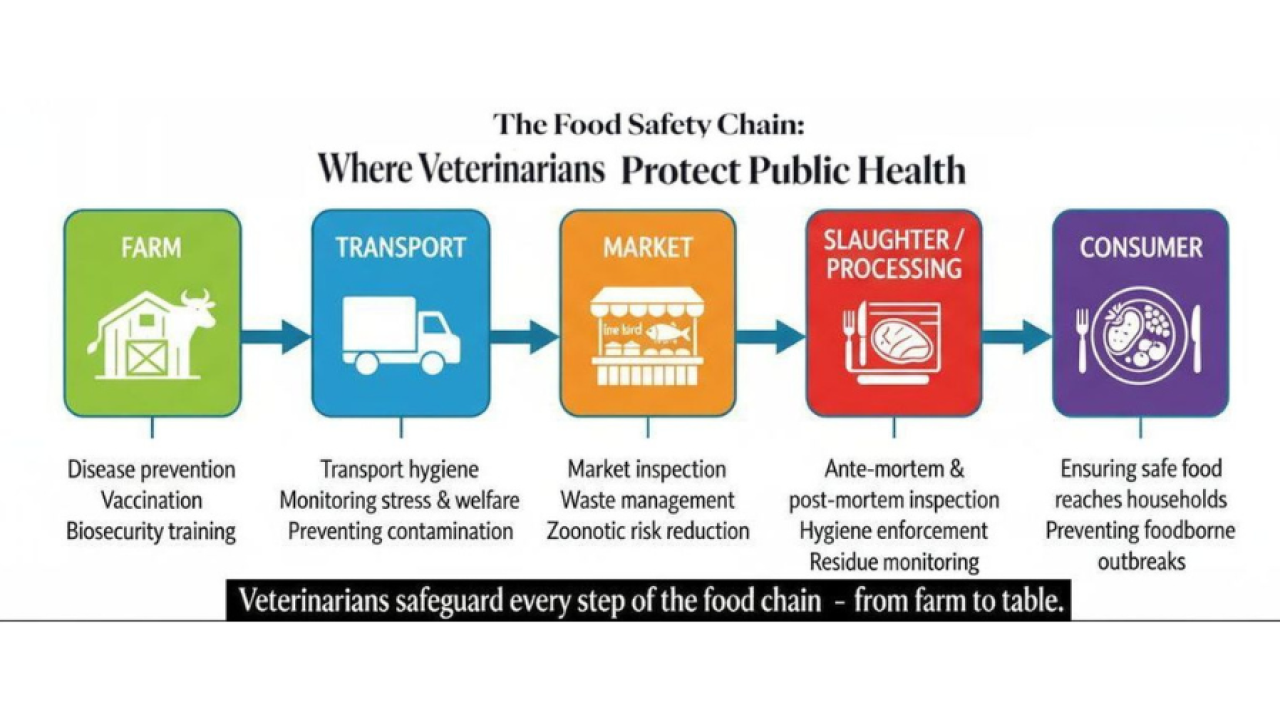

Food safety tends to attract attention only in moments of scandal: adulterated milk, chemical tainted fruit, a spike in hospital admissions after a festival. For the most part, however, food safety is an invisible infrastructure of trust. People eat what is available and affordable, trusting that someone, somewhere, is keeping it safe.

Later, he may inspect a slaughterhouse where conditions are far from ideal: inadequate drainage, poor knife hygiene, minimal use of protective equipment. His signature on an inspection form is meant to signal safety, but he knows how much remains beyond his control. In the afternoon, he might speak at a farmer training session on antibiotic use. The farmers listen politely, many will still go to the local drug seller who offers easy credit and a promise of "strong medicine."

The paradox is stark. Veterinarians are trained in epidemiology, pathology, microbiology, and public health. They understand how diseases jump species, how bacteria evolve under antibiotic pressure, how food becomes a vehicle for invisible threats. Yet the system often treats them as technicians for individual animals rather than strategic actors in national health security.

High‑income Asian countries offer a contrasting picture. In Japan, veterinarians are integral to public health centres, municipal inspection services, and national food safety agencies. In South Korea, veterinarians are embedded in systems that track hazards from farm to fork and work in tandem with human health professionals. Singapore has built a whole‑of‑government One Health model linking animal health, food safety, and environmental monitoring.

Bangladesh's veterinarians, by comparison, operate with fewer resources and less institutional backing. Many districts lack adequate numbers of public sector veterinarians. Private practitioners cluster in affluent areas or commercial farms. In villages, the vacuum is filled by "Quacks" for animals, individuals with varying levels of informal training.

Veterinarians are trained in epidemiology, pathology, microbiology, and public health. They understand how diseases jump species, how bacteria evolve under antibiotic pressure, how food becomes a vehicle for invisible threats. Yet the system often treats them as technicians for individual animals rather than strategic actors in national health security.

Weak veterinary coverage does not stay confined to animal health. It eventually appears in human case records, in hospital microbiology reports, and in the spread of resistant bacteria that no longer respond to standard treatments.

Food safety and the quiet infrastructure of trust

Food safety tends to attract attention only in moments of scandal: adulterated milk, chemical‑tainted fruit, a spike in hospital admissions after a festival. For the most part, however, food safety is an invisible infrastructure of trust. People eat what is available and affordable, trusting that someone, somewhere, is keeping it safe.

In Bangladesh, that trust is fragile. Live bird markets often operate with cramped cages, mixed species, limited hand‑washing facilities, and poor waste disposal. Slaughter is frequently performed on the floor, with minimal separation between live animals, carcasses, and customers. Meat inspection, where it happens at all, is cursory and under‑resourced.

Milk may be collected from multiple small producers, transported without refrigeration, and passed through intermediaries before reaching consumers. Contamination with E. coli, Salmonella, or Brucella can occur at many points. Fish ponds may be treated with antibiotics or chemicals to prevent disease and boost growth, often without guidance or monitoring.

Veterinarians are the professionals who should anchor this safety net. But for that to happen at scale, they need clear mandates, legal authority, laboratory support, and sufficient numbers.

Developed countries show how this can be done. Their food safety systems involve veterinarians at multiple points: approving slaughterhouses, monitoring processing facilities, certifying export consignments, and participating in risk assessments. Bangladesh has regulations and institutions responsible for food safety, but implementation is uneven, and veterinary expertise is not always fully integrated.

Antimicrobial resistance: A silent epidemic linking barn and bedside

If one issue crystallises the One Health challenge, it is antimicrobial resistance. AMR arises from the cumulative misuse of antibiotics across human, animal, and environmental sectors.

In Bangladesh, antibiotics are widely accessible without prescription. In the veterinary sector, this has led to widespread prophylactic and growth‑promoting use in poultry, cattle, and fish. Although many veterinarians are aware of AMR risks, they face pressures from farmers and market realities that encourage inappropriate use. Without diagnostic tools, clear regulations, and economic incentives, even well‑trained veterinarians struggle to enforce rational use.

On the human side, patients may demand antibiotics for viral illnesses, self‑medicate, or interrupt treatment courses. Hospitals and clinics with limited lab capacity may resort to broad‑spectrum drugs as a default. The bacteria, indifferent to disciplinary boundaries, simply adapt and persist.

Zoonotic bacterial diseases in Bangladesh have already revealed multidrug‑resistant pathogens circulating at the human–animal interface. Without coordinated One Health strategies, antimicrobial resistance threatens to erode our ability to treat even the most common infections.

Veterinarians must be empowered as stewards of antimicrobial use in animals. That means promoting preventive measures; vaccination, better housing, improved nutrition; over routine antibiotic use. It also means regulating the veterinary drug market and requiring prescriptions for critical antibiotics.

But AMR cannot be solved from the veterinary side alone. It demands joint surveillance of resistance patterns in humans, animals, and the environment, shared data platforms, and multidisciplinary committees that include veterinarians, physicians, microbiologists, and environmental scientists.

Learning from others: lessons across Asia

Japan, South Korea, and Singapore demonstrate what strong veterinary public health systems look like: integrated surveillance, strict food safety enforcement, and veterinarians embedded in public health institutions. Middle‑income countries like Malaysia, Thailand, and China have made progress in zoonotic disease control and food safety modernisation, though challenges remain in informal markets and AMR. Closer to home, India has begun articulating clear One Health strategies, with veterinary universities and ministries collaborating on zoonoses and AMR. Nepal, though resource‑constrained, has strengthened community‑based surveillance and participated in regional One Health initiatives.

When a veterinarian in Madaripur advises a farmer not to use antibiotics indiscriminately, when another in Khulna tests fish pond water for contaminants, when one in Rajshahi inspects a slaughterhouse and demands improvements, they are all participating in the same project: preserving the health of a nation.

Bangladesh is not absent from this regional movement. Platforms like One Health Bangladesh and national zoonotic disease prioritisation exercises show real commitment. Where Bangladesh often falls short is not in vision, but in implementation. Policies exist on paper, but frontline veterinary services remain underfunded. Coordination is discussed in workshops, but data systems remain siloed. International projects demonstrate success in pilot districts, but scaling up is slow and uneven.

Bringing human doctors into the circle

Too often, One Health is perceived as something that happens on the "animal side," with veterinarians expected to do most of the conceptual and practical work while human health largely continues as usual. This is neither fair nor effective.

Human doctors in Bangladesh see the consequences of weak animal health every day. They treat children with diarrhoea linked to foodborne pathogens, manage respiratory infections connected to live bird markets, and encounter sepsis cases driven by resistant bacteria shaped by antibiotic use in both human clinics and farms.

In Bangladesh, antibiotics are widely accessible without prescription. In the veterinary sector, this has led to widespread prophylactic and growth promoting use in poultry, cattle, and fish. Although many veterinarians are aware of AMR risks, they face pressures from farmers and market realities that encourage inappropriate use. Without diagnostic tools, clear regulations, and economic incentives, even well trained veterinarians struggle to enforce rational use.

Yet medical curricula still treat zoonoses and food safety as peripheral topics. Joint training sessions with veterinarians are rare. Outbreak investigations involving both sectors happen, but not routinely.

For One Health to move from rhetoric to reality, human doctors must be equal partners. This means sharing surveillance data, participating in joint risk assessments, and advocating for policies that recognise the upstream determinants of clinical problems.

One Health from the ground up

Even the most carefully designed policies struggle to succeed without genuine community participation. It is the farmers who ultimately decide whether to call a trained veterinarian or rely on an unregulated drug seller, whether to vaccinate their animals, whether to cull sick birds, or whether to quietly sell potentially infected meat to recover losses. Consumers, too, make daily choices about where to buy food and how seriously to take food safety warnings.

If Bangladesh is to build a resilient future; one that can withstand pandemics, protect its children from unsafe food, and keep lifesaving medicines effective; it must put veterinarians where they belong: at the heart of the One Health agenda.

Bangladesh's greatest strength lies in its social fabric. The country's long experience with community health workers, microcredit groups, disaster‑preparedness volunteers, and nationwide sanitation campaigns shows that behaviour can shift when information, trust, and incentives come together. Within this ecosystem, veterinarians, if properly supported and positioned, can become powerful catalysts for safer practices and healthier communities.

What Bangladesh must do now

Bangladesh has reached a point where the costs of inaction are too high to ignore. Zoonotic threats, AMR, and food safety failures are already eroding public health and economic stability.

Strengthening the veterinary sector is not a technocratic afterthought; it is a strategic imperative. That means training and deploying more veterinarians across the country, investing in laboratories, and giving veterinarians a formal seat at the table in national health planning, AMR committees, and emergency response structures.

Bangladesh does not need to reinvent its systems from the ground up. It can selectively adapt proven elements from developed Asian countries, tailoring them to local realities while working with regional and international partners to build long‑term capacity. Strengthening platforms such as One Health Bangladesh and ensuring they function not as symbolic bodies but as fully empowered operational mechanisms, will be essential to turning policy commitments into real‑world impact. Most importantly, the country must change how it sees veterinarians. They are guardians of food safety, custodians of antimicrobial stewardship, sentinels for emerging diseases, and essential partners in protecting human lives.

When a veterinarian in Madaripur advises a farmer not to use antibiotics indiscriminately, when another in Khulna tests fish pond water for contaminants, when one in Rajshahi inspects a slaughterhouse and demands improvements, they are all participating in the same project: preserving the health of a nation.

If Bangladesh is to build a resilient future; one that can withstand pandemics, protect its children from unsafe food, and keep lifesaving medicines effective; it must put veterinarians where they belong: at the heart of the One Health agenda.

Because the truth is simple: when animals are healthy, people are healthy. Unless we recognise and support those who keep animals healthy, we will remain dangerously unprepared for the challenges ahead.

Prof. Dr. K. B. M. Saiful Islam is a One Health activist, public health veterinarian, researcher, former Dean of the Faculty of Animal Science & Veterinary Medicine, and former Chairman of the Department of Medicine and Public Health at Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments