GREENWASHED

Two years ago, Humayun Kabir Salim decided to follow the government’s long-standing call for factory owners: going green.

Salim, managing director of Khantex Composite Textiles Ltd, planned to install a 1-megawatt rooftop solar system, enough to power around 200 homes annually, at his factory in Dhaka. The project, estimated to cost around Tk 6 crore, was meant to cut rising energy costs and improve efficiency.

The technology was available. The policy support existed. And the money, on paper, was there.

What Salim could not get was a bank willing to say yes, or no.

The spinner approached four to five banks and financial institutions. None rejected the proposal outright. Instead, the process dragged on, with repeated demands for documents and compliance papers.

“There was no outright rejection, but the process kept getting delayed with repeated documentation requirements,” Salim said.

Over time, the delays took their toll. “People eventually stop chasing these projects,” he added.

The entrepreneur believes the problem is not with the banks alone, but with a system that allows them to avoid accountability.

“The government has set big renewable energy targets, but there is no follow-up or obligation for banks to finance a fixed share or explain why they do not,” he said.

Salim’s case was not an isolated one.

Across the country, many small and medium-sized entrepreneurs planning green factory projects have run into the same wall. Funds exist, demand is there, but disbursement has been painfully slow. In some cases, it is stalled altogether.

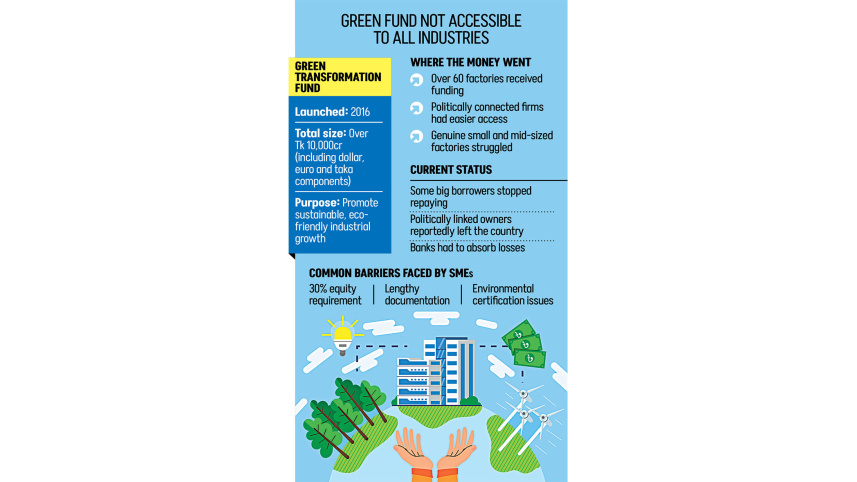

At the same time, some of the country’s most influential and politically connected business groups have had no such trouble accessing the Tk 10,000 crore refinancing fund. Its official name is the Green Transformation Fund (GTF), operated through the Bangladesh Bank (BB).

STRAIGHTFORWARD ON PAPER, SLOW IN PRACTICE

The GTF was launched by the BB in January 2016 as a long-term refinancing facility of $200 million, or Tk 2,443 crore. Its goal was to promote sustainable growth in export-oriented textile and leather sectors and support the country’s transition to a green economy.

In September 2019, the scope of the fund was expanded to include all manufacturer exporters, regardless of sector, for importing capital machinery and accessories for approved green and environmentally friendly initiatives.

Later, an additional €200 million, nearly Tk 3,000 crore, was added. In December 2022, another Tk 5,000 crore refinance fund was introduced to serve the same purpose.

Under the model, commercial banks lend to eligible factories or companies. The BB later reimburses the banks under the refinancing scheme.

According to central bank data, 30 banks signed participation agreements for the dollar component, and 26 did so for the euro component. Yet only 15 commercial banks have actually disbursed funds.

So far, more than 60 factories have received $140.94 million, or Tk 1,720 crore, and €71.21 million, or Tk 1,041 crore, representing 70 percent of the dollar allocation but only 36 percent of the euro allocation.

From the Tk 5,000 crore domestic currency fund, Tk 1,832 crore was disbursed to 68 clients through 20 banks as of June last year, about 37 percent of the total allocation.

Bankers say the lending process under the fund has become complicated because of its multiple components and other requirements.

Mercantile Bank, for example, distributed $8.9 million and €0.6 million to five recipients.

“The amount is affected because the higher formalities for GTF are stricter,” said a senior official of Mercantile Bank, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Earlier, GTF funds were disbursed directly in dollars and euros, which he said was simpler. Now that the funds are provided in taka, customers must provide at least 30 percent equity, while banks can finance a maximum of 70 percent.

“Sometimes factories say they cannot provide more than 10 percent equity at the moment, so the bank’s fund cannot be fully disbursed,” the official said.

He added that environmental certification requirements have also reduced uptake, making compliance more challenging for factories.

NOT ALL CLIENTS ARE THE SAME

While small and mid-sized firms struggled with equity requirements, paperwork and delays, some politically connected companies got large sums with ease, according to bankers.

Among them was S Alam Group, one of the country’s most influential conglomerates.

Two of its subsidiaries, Infinia Spinning Mills and Infinia Spinning Mills 2, jointly received $21.36 million and €3.3 million, or about $3.90 million, from Social Islami Bank Ltd at concessional interest rates under the GTF.

Another company owned by Belal Ahmed, the son-in-law of the S Alam Group chairman, also tapped the fund. Ahmed’s Unitex LPG Limited borrowed €12.6 million, or $14.90 million, from Islami Bank Bangladesh PLC in August 2021 under the same scheme.

Today, all of them are defaulters. The owners are reportedly abroad. The banks are left holding the losses.

Bankers allege the loans were approved under political pressure during the previous Awami League government, bypassing standard risk assessments and checks on project viability.

The Daily Star approached Belal Ahmed, but he could not be reached by phone.

“Belal sir is now staying abroad. We can’t talk about this issue,” an official of Unitex LPG Limited told The Daily Star.

As borrowers stopped repaying, the problem spread beyond individual banks.

“A special audit found that the two units of Infinia Spinning Mills alone owe several hundred crores to Social Islami Bank Ltd and have already defaulted,” according to a BB official, who asked not to be named.

“A case has been filed in this regard. Ultimately, they brought the bank into trouble,” said a senior official of Social Islami Bank Ltd.

“These were good firms once, but after the 2024 political changeover, their owners fled, and operations collapsed. We are trying to sell the companies to recover our funds, but we fear we would not get fair prices,” he said.

As defaults mounted, the BB stepped in.

According to Islami Bank Bangladesh PLC, the central bank deducted nearly €7.2 million, or $8.7 million, from the bank under its refinancing facility because of overdue payments linked to Unitex LPG Limited.

Islami Bank Managing Director Omar Faruk said the company defaulted after receiving the GTF loan in 2021.

“They are not making any repayment on that loan, so we will have to repay it ourselves by creating a new loan,” he said.

Asked whether political influence played a role, he said, “Of course, there was political influence.”

“The entire bank -- everything -- used to operate at their signal. There’s no scope to deny it. Bangladesh Bank would even lower the valuation and release the funds. It was effortless for them,” he said.

He added that the bank is now working with the BB to recover the money.

“Ultimately, we cannot leave BB’s money unrecovered. We may have to create a forced loan, impose the liability on them, and proceed with legal action. We have already initiated the process,” he said.

A case over the loan has already been filed.

‘FINANCIAL INJUSTICE’

Khondaker Golam Moazzem, research director of the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), described the situation as “financial injustice’. “This is straightforward financial injustice as funds remain undisbursed and misused despite demand among SMEs.”.

“Because of this discrimination and misuse, the economy is being deprived of the benefits a functioning banking system should deliver. It is a systemic failure.”

He said the damage is twofold: climate-linked funds lose their intended environmental impact, and banks fall deeper into default.

“The cost of these defaulted loans is ultimately pushed onto depositors through higher interest rates,” Moazzem said.

M Zakir Hossain Khan, chief executive officer of the Change Initiative, a renewable energy think tank, said the structure of the fund itself needs rethinking.

He suggested shifting such funds from the Bangladesh Bank to the finance ministry and creating a dedicated annual startup fund, allowing innovators to access Tk 10 lakh to Tk 50 lakh without collateral based on merit.

Ideas, he said, should be pitched before expert panels rather than filtered through bureaucracy.

Zakir also proposed setting clear timelines so funds are released within three to six months, and earmarking 50 percent of funds for SMEs and CMSMEs, with at least 25 percent allocated to innovation every year.

COMMERCIAL BANKS ULTIMATELY BEAR THE BRUNT

The central bank does not acknowledge a default problem in the green fund.

In a written statement, BB spokesperson Arief Hossain Khan said, “The repayment of the instalments of the refinancing by the concerned banks is continuing.”

An official from the Sustainable Finance Department said that under the refinancing scheme, the central bank ultimately recovers its money from commercial banks.

“As a result, the central bank does not bear the financial strain, while commercial banks often find themselves in a critical situation,” he said.

On the lower disbursement, Shah Md Ahsan Habib, a professor at the Bangladesh Institute of Bank Management (BIBM), said constraints exist on both the demand and supply sides. On the demand side, entrepreneurs do not yet see a clear business case for green transformation.

He emphasised the need for two reforms: simplification and stronger incentives.

“Simplification is necessary for any BB refinancing package, while incentives must be enhanced. The existing incentives, such as marginal tax reductions, are simply not enough,” he said.

On the supply side, Habib pointed to banks’ risk aversion and equity-related concerns.

He noted green financing remains largely experimental. “Default risks are uncertain, and these are not yet proven sectors, which makes banks particularly cautious,” he added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments