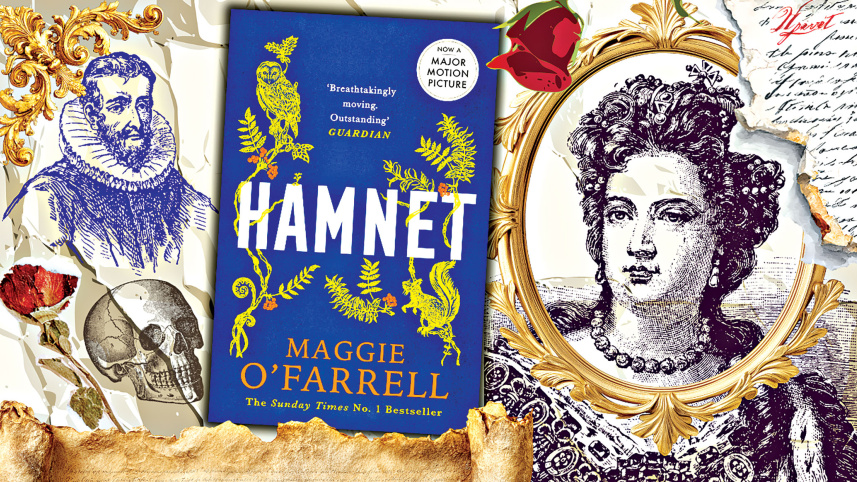

Through Agnes’ eyes: Reimagining Shakespeare’s lost years in ‘Hamnet’

One of the great pleasures of reading enough of the plays of William Shakespeare is that, after a while, you feel like you know him. British actor Patrick Stewart famously stated, “...he feels like an old friend—someone who just went out [...] to get another bottle of wine.” While Shakespeare scholars have succeeded in creating a rough Shakespeare biography based on historical documents, many of them will admit that there are large gaps in our knowledge. We know the names of Shakespeare’s family members as well as the dates of their baptisms, marriages, and deaths. But we remain ignorant of their personalities and family dynamics. Northern Irish novelist Maggie O’Farrell’s historical fiction novel, Hamnet, attempts to give flesh and personality to our bare bones understanding of these historical figures. Her work illustrates the story of Shakespeare’s meeting with his wife and how the death of their only son, Hamnet, led Shakespeare to write his magnum opus Hamlet (1623).

The plot of the novel centres around Shakespeare’s wife Agnes (pronounced Ann-yis). Better known as Anne Hathaway, O’Farrell chose to call the character Agnes as it was the name that her father, Richard Hathaway, used for her in his will. The author portrays Agnes as almost otherworldly. The daughter of an unnamed wood-dwelling woman, Agnes was most at peace in the forest. She had a vast knowledge of the local plants, which she used to create treatments for her family and neighbours. She was a skilled beekeeper, and she even had a trained kestrel. Most importantly, she could see into the future. When Agnes’ birth mother died in childbirth, her father married another woman named Joan, whom Agnes constantly clashed with. When her father dies, Agnes is left isolated under her stepmother’s watchful eye with her brother Bartholomew as her primary ally. The depiction of Agnes’ family life certainly offers a compelling reason for why she would be drawn to an 18-year-old William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare is the secondary character in the novel. O’Farrell deliberately leaves Shakespeare unnamed. Referring to him only as “the Latin tutor” and later as “the husband” and “the father.” This depiction of Shakespeare is based on his likely education at the Stratford grammar school where he would have been intensely educated in the Latin language. O’Farrell places Shakespeare in an emotionally and physically abusive relationship with his father, the glover and former town bailiff John Shakespeare. This portrayal of the abusive John Shakespeare is based on the historical figure’s social and economic decline. Shakespeare sees the mysterious and beautiful 26-year-old Agnes, with a proper dowry, as a means of escaping his father’s house and starting a household of his own,

The plot of the novel centres around Shakespeare’s wife Agnes (pronounced Ann-yis). Better known as Anne Hathaway, O’Farrell chose to call the character Agnes as it was the name that her father, Richard Hathaway, used for her in his will.

Shakespeare scholars know from the date of Shakespeare’s marriage to Anne Hathaway in November 1582, and the baptism of their first daughter Susanna Shakespeare on May 26, 1583, that Anne must have been pregnant during the wedding. While these circumstances have led some to speculate that Shakespeare and Anne’s marriage was the forced result of an unplanned pregnancy, the novel posits that Shakespeare and Agnes intentionally became pregnant to force their parents to accept their handfast engagement to one another. O’Farrell clearly imagines Shakespeare and Agnes as marrying out of love.

O’Farrell also explains how Shakespeare ended up working in the London theatre companies. In the scholarship, Shakespeare disappears from the historical record between the baptism of his twins, Judith and Hamnet, in 1585 to the first reference of Shakespeare as a London player and playwright in 1592. Often called “The Lost Years,” scholars don’t know why Shakespeare left Stratford or how he ended up in the London theatre companies. The story suggests it was Agnes who encouraged Shakespeare to move to London to set up a branch for his father’s glover business. Agnes is motivated by a desire to help her husband escape the emotional and psychological burden of living under his father’s roof. Shakespeare ends up selling gloves to the theatre company before eventually joining them.

The novel also explores the circumstances of Hamnet’s death in 1596, and whether it had any connection to Shakespeare writing his play Hamlet. The cause of Hamnet’s death isn’t listed in the Stratford Parish records, but O’Farrell conceives of Hamnet dying from pestilence. She crafts a heartbreaking story of Judith originally getting sick with Agnes extending all her efforts to save her daughter only to discover that Hamnet has become sick and to have him die despite her efforts to save him. O’Farrell beautifully captures the pain that the Shakespeare must have felt over Hamnet’s death. She has Shakespeare briefly return to Stratford for the death only to return to London to escape his grief despite Agnes’ request that he stay in Stratford with his family.

The climax of the book occurs when Agnes travels to Shakespeare’s theatre in London to witness a performance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. In her novel, O’Farrell contends that Shakespeare was not only inspired by the death of his son to write the play, but that he modeled Hamlet after Hamnet. The text describes how Agnes is overwhelmed by the sight of the actor who has transformed into what her son would have looked like had he grown to manhood. O’Farrell has Shakespeare himself play the role of the ghost and Agnes bears witness as father and son symbolically reconnect with one another on stage. O’Farrell writes, “[Agnes] sees her husband, in writing this, in taking the role of the ghost, has changed places with his son”. O’Farrell’s decision to cast Shakespeare as the ghost is clearly inspired by Shakespeare biographer Nicholas Rowe’s theory on the casting of the ghost role. There is something metatheatrical about the idea of the mother watching her husband embrace their symbolic son in a play about a broken family.

If I had to critique anything about the novel, it is that I wanted O’Farrell to spend more time exploring Shakespeare’s process of writing Hamlet. We know Shakespeare was a great adaptationist who drew upon source material like Saxo Grammaticus’ HistoriaDanica and François Belleforest’s Histoires Tragiques. I would have loved her to depict Shakespeare using these texts to weave together his version of the story.

Regardless, O’Farrell’s Hamnet is one of the most compelling depictions of Shakespeare’s family life that I have ever encountered. O’Farrell’s Agnes is a Shakespearean heroine in her own right, and she brings a breath of much-needed humanity to the historical figure of Anne Hathaway. By showing us the story through Agnes’ eyes, we gain insights into the young man whom we have all previously believed we knew so well.

Jonah Kent Richards is a Shakespeare screen adaptation scholar, an English teacher, and contributor for Star Books and Literature.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments