On his 76th death anniversary: The other side of George Orwell

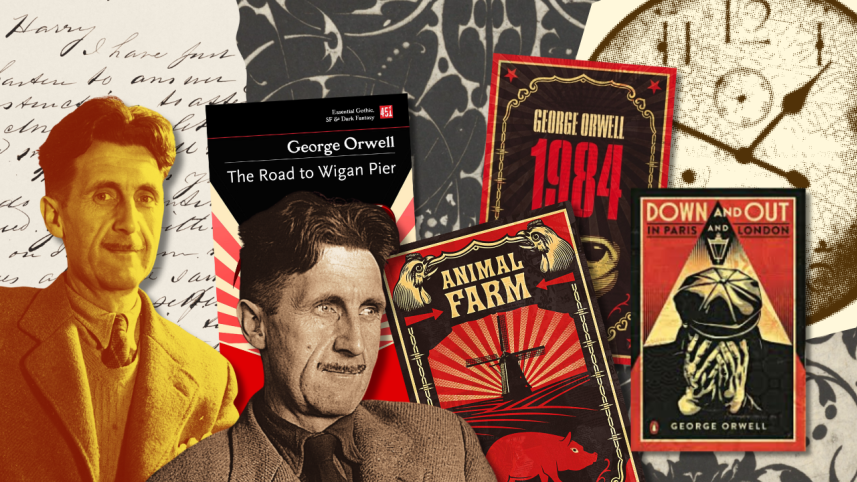

It is undoubted that George Orwell is one of the most important political writers of the 20th century. Labelling him a political writer reflects how deeply his life and works were influenced by the events he lived through. Though Orwell died in 1950 at the age of 46, his last two fictions—Animal Farm (1945) and 1984 (1949)—brought him enormous fame worldwide. In these two fictions, Orwell expressed deep anguish about Stalin, Soviet communism, and totalitarianism. Perhaps, for this reason, many saw Orwell as an anti-communist writer who sold his soul to capitalism.

My generation matured during the 1990s—after the fall of the Soviet Union. I read a Bangla translation of Animal Farm before I entered college. Like myself, many youths knew about communism through Animal Farm, and to them, communism is representative of Stalin’s Soviet Union. The same can be said for 1984. After its publication in 1949, most of the readers believed that it portrayed Stalin’s Soviet communism. Almost no one thought of this fiction as a portrayal of surveillance, propaganda, and totalitarianism of Nazi Germany at the time, which was openly fascist and capitalist. Despite Orwell’s reductionist image as an ‘anti-communist’ writer, Orwell's life and his nonfictions prove that he was deeply committed to socialism till the end of his life.

Orwell wrote an autobiographical essay, “Why I Write”, in 1946, where he pointed out four reasons why writers write. The first one is sheer egoism: to express oneself—to be known to all, and to be praised by all. The second one is aesthetic pleasure: love towards language and the beauty of the world. The third one is historical motivation: to document events for future generations truthfully. And the fourth one is for political purposes. Orwell believes no artwork is politically neutral. The statement, “art should maintain distance from politics”, he claims, is itself political. Orwell confesses honestly that his writing has been formed by his political belief and experience. Orwell did not believe in “art for art’s sake”. Rather, he writes to expose lies and bring out uncomfortable truths.

Many events made Orwell a political writer. Orwell worked in Burma for five years (1922–1927) in the imperial police, where he faced everyday cruelty and hypocrisy of British colonialism. He saw how colonial powers worked through instilling fear and inciting violence. Essays like “Shooting an Elephant” (1936) and “A Hanging” (1931), and novels like Burmese Days (1934) carry Orwell’s anger, frustration, and inner conflicts about the British Empire. In a similar tone, his travel writing on French-occupied Morocco in 1939, “Marrakech” (1393), is also significant.

After returning to England from Burma, Orwell was plunged into abject poverty. During this time, he also lived in Paris for two years and understood living inside the iron reality of a society which is divided into various classes. In Paris and later in London, Orwell walked like a vagabond, spent enormous time with the poor and homeless, and lived on mere wages. His first nonfiction, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), was written on his experience with poverty and the poor. Despite the book’s style of storytelling, it is profoundly a political book, which is formative in Orwell’s writing career. Through writing this book, Orwell received a clear picture of the working class. He writes, “poverty is what I am writing about…the slum was first an object-lesson in poverty, and then the background of my own experiences”.

After firsthand experience of poverty, Orwell turned to the English working class. He lived for almost two months with coal miners in Lancashire and Yorkshire and published his first political book, The Road to Wigan Pier (1937). He wrote that the purpose of living with coal miners and unemployed workers was “necessary to me as part of my approach to Socialism”. The first part of this book is very vivid, ethnographically written about the daily life of the miners. Orwell’s diaries and letters also proved that he contacted at least two social anthropologists in England about how to import ethnographic writing techniques during the writing of this book.

Orwell made an incredible journey to the bottom of a mine and after reaching the coal face, he compares it with Dante’s “Inferno” (1321): “most of the things one imagines in hell are there—heat, noise, confusion, darkness, foul air, and, above all, unbearably cramped space.” He mentioned that giant corporations made millions of pounds out of these mines but the miners received very little; capitalism is its dirtiest. The Road to Wigan Pier (1936) proves that nothing had changed among the working class since the publication of Friedrich Engels’ Condition of the Working Class in England (1845) one hundred years ago.

The second part of the book is highly political and controversial, but Orwell was honest about his opinion. He knew that the readers of this book would be British Left liberals, but he did not hold back in criticising his fellow socialists. Orwell started with the question, if socialism is capable of improving the working class condition, then why aren’t we all socialists? He clears his intention at the outset by saying, “And please notice that I am arguing for socialism, not against it”. He argues that it is the working class who understands socialism more authentically than any other class because “Socialism does not mean much more than better wages and shorter hours and nobody bossing you about.”

He complains that the working class does not understand the language of the Left. So, the success of socialism, to him, depends on the connection between the working class and the Left middle class. After coming back from the coal mines, Orwell convinced himself that socialism was the common-sense answer to this dire situation of the working class in England. This reminds us of his famous line, “Every empty belly was an argument for socialism”. Interestingly, Orwell’s ‘emotional socialism’ did not satisfy the British Left during that time. When the book was published, another socialist, Victor Gollancz—the publisher of the Left Book Club—wrote the Preface of The Road to Wigan Pier and called for ‘Scientific Socialism’.

According to all biographers, Orwell’s participation in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) was a decisive moment in his life. In 1936, Orwell enlisted himself in the POUM (the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification) to participate in the Civil War to support the Republicans against the Fascist General Franco. The militias of the Republican faction consisted of several parties, including socialists, communists, Marxists, workers, trade unionists, etc. Orwell spent seven months in Spain, including time at the fronts, where he witnessed workers and militias fighting side by side against the fascist nationalists. At the front, later, Orwell was shot in his throat too.

Orwell also witnessed street fights between Socialist and Communist factions-a civil war within the Civil War. Many POUM leaders were tortured and killed by Communist allies. As a volunteer of POUM, which followed Leo Trotsky, Orwell literally fled Spain with his life. After returning to England and finishing the draft of Homage to Catalonia (1938)—one of the best books ever written on the Spanish Civil War—Orwell struggled to find a publisher because no one was interested in knowing how the fight against fascism bred infighting and factions within the Left. Orwell realised how the International Left was lumped under Stalin’s Soviet leadership with a blind loyalty to communism.

When Hitler bombed England in 1940, Orwell came up with a curious response at a time of existential threat to his motherland. Next year, in 1941, he published The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius, a very long essay in the form of a book where he supported the war out of patriotism and strongly believed that England’s class system hindered the war effort and that Britain needed a socialist revolution to defeat Germany. Knowing the fact that the Left often teases patriotism as “the flag-waving fetish of wannabe fascists or rural huckleberries”, Orwell argues patriotism is just the opposite of such conservatism in a time of war.

Orwell believed the war would destroy capitalism and pave the way for socialist transformation in England. He claims, “We cannot win the war without introducing Socialism, nor establish Socialism without winning the war”. In one sense, that was true because after the war, no one wanted to go back to pre-war England. In this book, Orwell gave a long definition of socialism as: “Socialism is usually defined as ‘common ownership of the means of production’…”. He enthusiastically came up with many concrete socialist tenets such as equality in income, nationalisation of the economy, democratisation of all education, goodbye to all hereditary privileges, and political democracy.

Though Britain won the war, it turned into the biggest loser in the allied forces. It also lost its Indian Empire. The economy died and the future was bleak. The opportunity for socialist transformation that the war provided passed without any immediate success. Orwell’s health began to fall. It was at that time that Orwell finished Animal Farm and 1984.

Fahmid Al Zaid is associate professor in Department of Anthropology, University of Dhaka, and a PhD candidate at Durham University, UK. He can be reached at fahmidshaon@du.ac.bd.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments