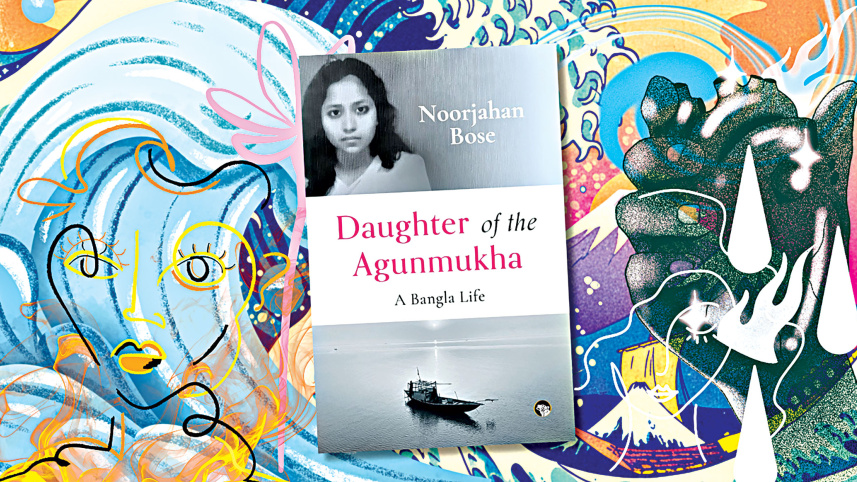

A firebrand’s journey to Washington from Barisal

“Agunmukha” translates to “fire-mouth” in English. The word mirrors the tumultuous life of Noorjahan Bose, shaped by her early years in cyclone- and flood-prone small towns of Barisal; her experience of sexual violence at the age of 10; the loss of Imamuddin, her first love and husband, to smallpox; single motherhood; and her later marriage to Swadesh Bose, a Hindu man—an interfaith union opposed by society. Noorjahan Bose accepted all of these as challenges, because for her, a firebrand, being defeated by life or giving in to society’s unreasonable demands was never an option.

In Barisal, despite the natural disasters, her childhood was a happy one. Several families lived in single units within an area where visiting and consulting one another on matters both significant and insignificant, sharing meals, playing and enjoying all the perks that a rural setting offers (fishing, bathing in the rivers and ponds, enjoying the fresh vegetables, fruits, and climbing the trees that bore them) were the norm. But they also lost family members and relatives to floods and cyclones.

The descriptions of the floods in Barisal are very vivid in the book. The force of the water, its power to destroy entire villages and to mercilessly take lives, shows us how the inhabitants of flood-prone areas have learned survival skills and be resilient. People place their dry food like rice and spices in containers and place them in sacks to retrieve them when the flood waters recede. Other useful information in the work include what relief goods are most required: water-purification tablets, cholera vaccine, essential medicine, bandages, clothes, etc.

Life was wonderful in Bose’s teen years in Barisal till the Hindu-Muslim riots led her to question religion itself. If faith led to taking human lives, she wanted no part of it. Her husband Swadesh Bose believed in leftist politics and religion had no place in his life. It was ironic indeed that society had this much antagonism towards their interfaith marriage when faith was not important to either of them. A Muslim fanatic in Washington even threatened to kill her because she had insulted Islam by marrying outside her faith.

Her political consciousness started in school when, during the Language Movement, she staged a walkout from the classroom holding banners in support of the movement. The school had to take disciplinary action against her, as Barisal was part of West Pakistan then, but the headmaster later told her, “I wish I had a daughter like you”. She also observed the elders in her family participating in elections, canvassing, delivering fiery speeches, etc.

Unfortunately at age 10 she was sexually abused by an uncle. No one would believe her if she told on him. He was, after all, a respected person in society. He was the only elder considered safe to entrust her in his care, escort her to other relatives’ houses, and even to stay in his home. Wasn’t she safe in his home as he had a wife and children of his own? She was not. Eventually, the daughter of Agunmukha finally flashed a knife at him and the nightmarish violations came to an end.

In her book, Bose has expressed how important it is to talk to children as early as possible about how to protect themselves from sexual predators. She herself had no idea of what to make of the rogue uncle’s actions. She wondered if his actions were normal. Did he love her more than he loved his other nieces? Like us all, she also expresses disappointment at how the law hardly protects victims of sexual abuse.

After this, she states that her happiest years were with Imadullah, a Jubo League worker whom she married and had a son with. He was from among the small minority who did not believe in the efficacy of the smallpox vaccine. His mother’s amulet would protect him, he believed. Unfortunately he died of the disease and Bose was devastated. The devastation worsened when she saw the rituals that widows must follow. She had no say in when her husband would be buried and what burial rites should be followed. Worst of all, she could not see or touch him because the death of a spouse meant that the marriage was null and void; she was deprived of a last farewell sentence to her dear Imad. But as Imad’s widow, she was intelligent enough to choose a white sari with a zari border for her marriage ceremony to Swadesh Bose.

She calls her life in Cambridge “Another Life”. Because of her curious nature and a reader of books, she observed, learned and even adapted to the western culture. She made efforts to know English. She was, however, surprised to learn that women’s rights were not ideal even in this “developed” country and sexual abuse of women was remained as an unaddressed problem.

Her descriptions about watching the ballet “Swan Lake” at the Royal Albert Hall, being invited to the Queen’s garden tea party at Buckingham palace and visiting Stratford-on-Avon to reminisce her favorite Shakespearean characters, seeing the magnificence of the camellias and rhododendrons in Kew Gardens were a delight to read.

At Oxford she enjoyed her life in the same way as she did in Cambridge, but she was disappointed in her encounter and assessment of Nirad Chaudhuri, author of The Autobiography of an Unknown Indian. Written in 1951, it was well received as it had in-depth analysis of the recently independent India. He had come to Calcutta after spending his early life in Kishoreganj, East Pakistan, but now at Oxford, he criticised Bengalis, their culture and cuisine. He also had a deep disdain for the working class. Noorjahan Bose’s disappointment in him was complete when she saw his wife malnourished and wearing a patched and torn sari. The wife told Bose matter-of-factly that all their earnings went to supporting Nirad Chaudhuri’s lavish western lifestyle.

Like every Bengali, she was delighted to witness an independent Bangladesh, but was disappointed when her husband was not considered for a post in the Planning Commission of the new independent country. She concluded that his being a Hindu had much to do with it. She cites other instances when landlords (in Karachi) would not rent their homes to a Hindu tenant. There are several instances of ill-disguised disapproval of Swadesh Bose being Hindu. Religious intolerance is a distinct theme in the book.

Her life in the USA was very fulfilling. On her return to Bangladesh, she worked tirelessly for women’s rights, preventing early marriage and ensuring justice for sexually abused women.

In conclusion, this book is inspiring and is an easy read. Her message is that women especially need to be brave, be eager to learn, and adapt to change. The key to succeeding in life is education and having an open mind. Despite narrations of the difficulties she faced in life, Daughter of the Agunmukha is a feel-good book.

Nusrat Huq is a senior teacher in Sunbeams school.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments