Transboundary rivers treaty: Crucial for our future

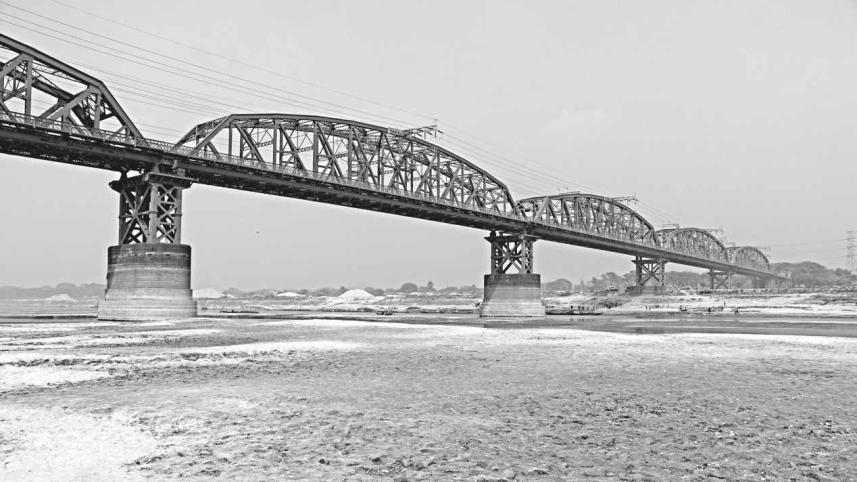

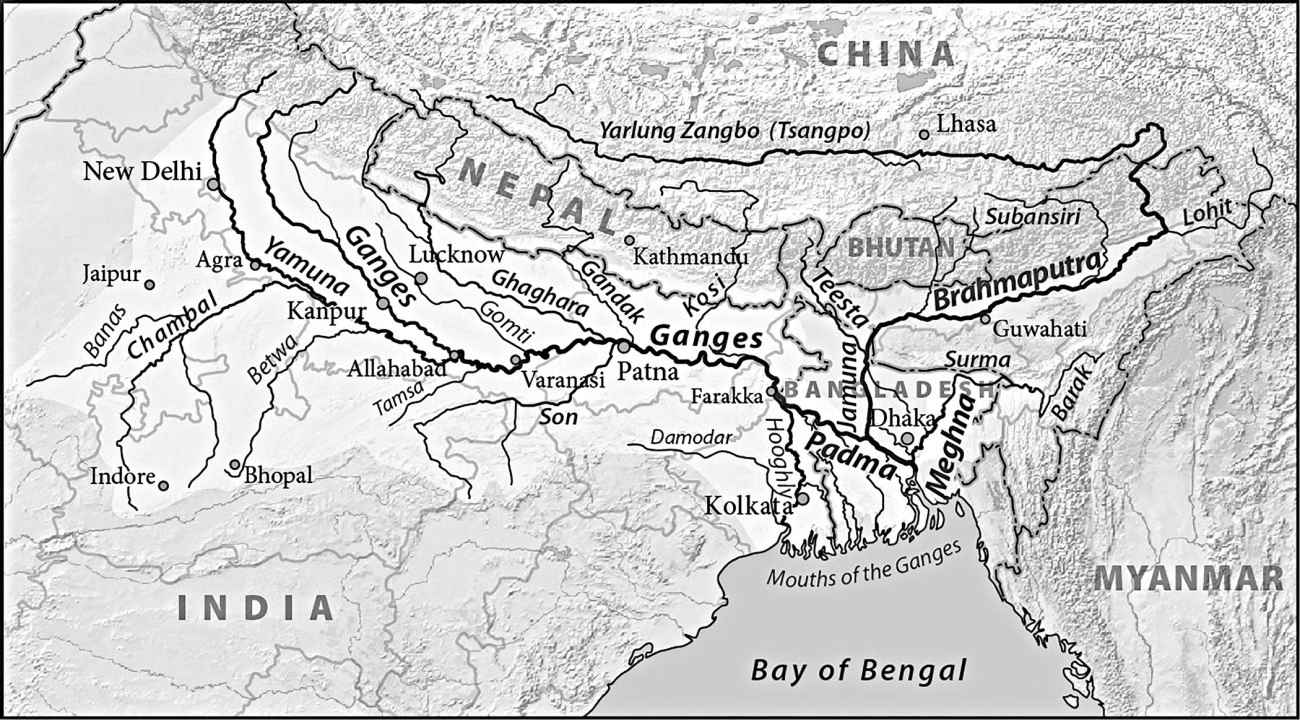

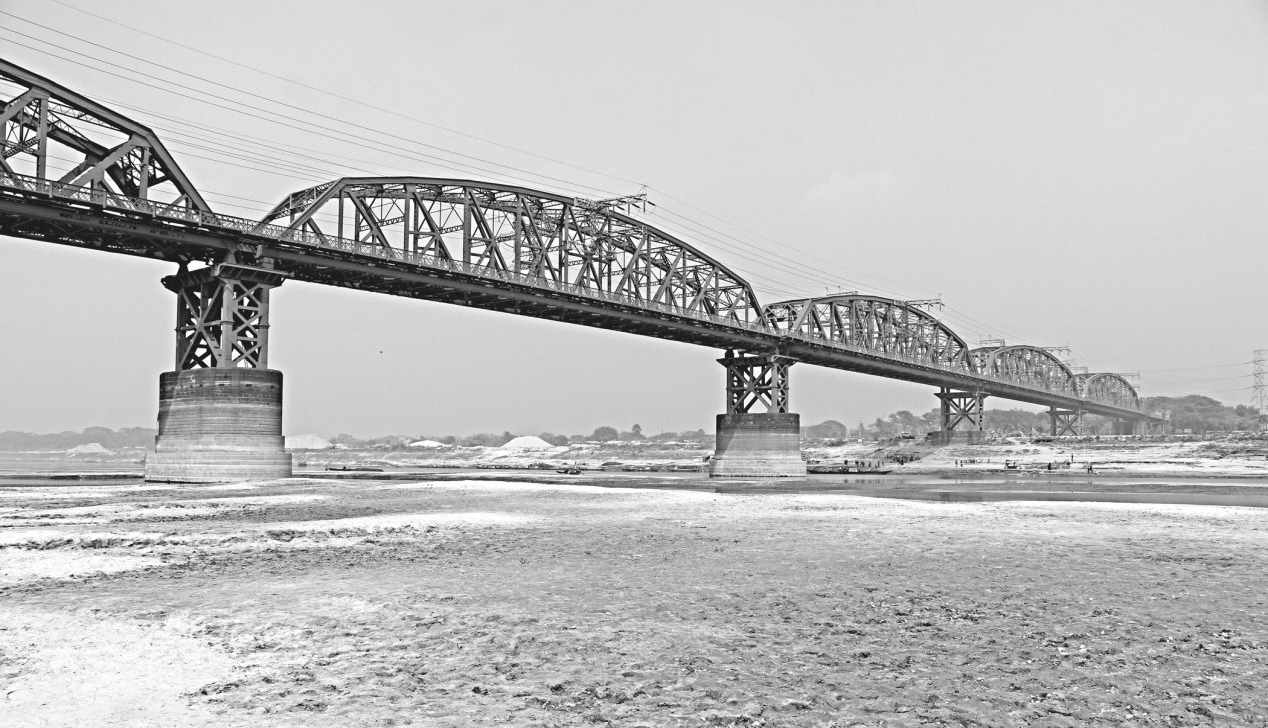

A pre-liberation time slogan, “Tomar amar thikana – Padma-Meghna-Jamuna (the Padma-Meghna-Jamuna is our address),” depicts the inherent connection of rivers to the very existence of Bangladesh as a country. The geographic territory of Bangladesh is created by river-borne sediments over a long period of geologic time. All major rivers that flow into Bangladesh originate outside the country’s boundaries. In that sense, Bangladesh does not have any control over the river flow in transboundary rivers that are vital to her economy, ecosystems, and survival. Bangladesh is located at the most downstream part of the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) basins, which span over parts of China, India, Nepal, and Bhutan. Although only 8% of the basins belong to Bangladesh, 25% of the 600-million population in the GBM basins live here. Of the 54 transboundary rivers that are shared among the countries in the GBM basins, there exists only one 30-year treaty between India and Bangladesh on the sharing of Ganges water during lean months. The Ganges Water Sharing Treaty will expire at the end of 2026. The Ganges basin spans India, Nepal, and Bangladesh; however, the treaty was signed between India and Bangladesh only. There exists a separate treaty between India and Nepal on the flow of the Gandak and Kosi Rivers, which are tributaries of the Ganges River.

It is widely accepted that river basins are single entities – despite flowing through different states or countries – and should be managed as such. All international laws, rules, and principles that deal with the management and planning of transboundary rivers promote the concept of integrated water resources management at the basin scale. For example, the UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (1997) is a global treaty providing a framework for cooperation, management, and protection of shared river basins for uses like drinking, irrigation, and energy, emphasising principles of equitable and reasonable utilisation, not causing significant harm, and the obligation to cooperate. This law serves as a backbone for bilateral agreements on shared freshwater resources. Another example of integrated water resources management involving all stakeholders is the European Water Framework Directive (WFD), which considers the interconnections between surface water, groundwater, and related ecosystems in transboundary rivers. Several successful water resources management treaties that are based on the WFD in Europe include the Central Commission on Navigation on the Rhine (CCNR), the International Commission on Protection of the Rhine (ICPR), and the Danube River Basin Monitoring Network (DRBMN).

The Ganges Water Sharing Treaty of 1996 also recognised the need for basin-scale management of the Ganges and other transboundary rivers. The Ganges Treaty provided a good framework for collaboration between India and Bangladesh and paved the way to reach long-term agreements on other transboundary rivers. However, the Ganges Water Sharing Treaty is not a comprehensive plan to manage water, sediments, and energy generation potential in the basin involving all stakeholders. Besides, the treaty only deals with water sharing during the lean season – not throughout the year. The Ganges Treaty does not have a guarantee clause to ensure the discharge of the agreed-upon amount of water at Farakka Barrage to Bangladesh.

Unfortunately, the treaty fell short in fulfilling the obligations to discharge the agreed-upon amount of water at Farakka Barrage to Bangladesh. Several published studies that are based on data available from the Joint River Commission (JRC) for the period 1997–2016 reported that Bangladesh did not receive the agreed-upon amount of water 52% of the time. In addition, Bangladesh did not receive the agreed-upon amount of water 65% of the time during the three guaranteed periods between March 11 and May 10 during the same study period.

The water scarcity during the dry season in the Ganges leads to loss of navigation, groundwater depletion in the Ganges-dependent region in the southwestern part of Bangladesh, upstream salinity intrusion in freshwater rivers and crop fields, and changes in freshwater-fish species composition. Bangladesh does not have any control over the flow in the transboundary rivers during the monsoon, which results in untimely flooding and riverbank erosion. People in the Ganges-dependent region are losing their homes to riverbank erosion and flooding. For example, a study published in 2019 in the Journal of the American Water Resources Association (JAWRA) reported that the hydrologic characteristics of the Ganges-dependent region in Bangladesh were modified significantly between 2001 and 2014.

The reduction in freshwater flow increased the extent and intensity of salinity in 11 out of 14 measuring stations in Khulna, Jessore, and Satkhira districts. The amount of agricultural land in the area declined by 50%, rural settlement declined by 20%, and freshwater bodies declined by 38% during the study period between 2001 and 2014. The study also reported that the direct damage to Bangladesh’s economy is about $3 billion. The Farakka Barrage has caused significant damage to the Indian economy as well. Waterlogging and recurrent flooding have increased upstream of the Farakka Barrage in parts of West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh. Navigability of the Kolkata Port remains unfulfilled, although that was the motivation for building the Farakka Barrage.

The reduction of lean-season flow at the Farakka Barrage is caused by other dams and diversionary structures built by India and Nepal at upstream locations. As per a report by the World Economic Forum published in 2019, the Ganges is being throttled by more than 300 dams and diversions, with many more blocking its tributaries, stopping the natural flow of the river. Since the Ganges Water Sharing Treaty is an agreement between upstream India and Bangladesh, it is the responsibility of India to abide by the agreement.

The newly elected government in Bangladesh will have to formulate a new treaty for sharing the water and sediments for all transboundary rivers in general and for the Ganges in particular. In new negotiations with India and potentially with other co-riparian countries in the GBM basins, the government of Bangladesh will have to document the hardships and crises that the country faces due to scarcity of flow in the Ganges and in other rivers in terms of economic losses, destruction to the ecosystems, and human health. The flow data need to be shared in the media so that the people and researchers can participate in the decision-making process.

Water scarcity should not be discussed only in light of the losses in navigation, agriculture, irrigation, industry, and fisheries. It needs to be viewed from a planetary health perspective, which should include recognition of the impact of climate change on ecosystems, environment, and public health.

Bangladesh should advocate for a basin-scale integrated water and sediment management compact involving India and Nepal in the discussion on renewal of the Ganges Treaty. Similarly, Bangladesh should work with China, India, Bhutan, and Nepal to reach a long-term compact on the Brahmaputra River basin management. A compact is an agreement among all stakeholders in a river basin for conservation, utilization, development, and control of water and related resources under a holistic, multi-purpose plan to bring the greatest benefits and the most efficient service for all parties involved. A compact is a far more visionary management plan for transboundary watercourses than a mere water-sharing treaty. A compact can benefit both upstream and downstream stakeholders. Under a compact, a feasibility study can be carried out to identify multiple uses of water resources in the GBM basins, which can include water retention reservoirs built at upstream locations to store water for electricity generation, recreation and tourism purposes, and augmentation of lean-season flow at downstream locations. Under a compact, the cost-sharing agreement will have to be reached among co-riparian nations.

The new government in Bangladesh needs to approach transboundary water resources management with an open mind. It needs to work with India in dealing with China on the management of the Brahmaputra River basin. Bangladesh’s new parliament should ratify the UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (1997) as the first order of business. The GoB should encourage India and other co-riparian nations to use the UN Convention as the basis for negotiation to settle all transboundary river issues. If necessary, Bangladesh can propose holding a convention on transboundary river issues involving development partners, such as the World Bank, IMF, EU, JICA, DFID, USAID, and other pertinent parties.

Bangladesh should put hydro-diplomacy at the centre of all diplomatic dealings with countries in the GBM basins. In other words, Bangladesh should keep the issue of transboundary rivers in mind when deciding on other treaties, agreements, and business dealings with China, India, Nepal, and Bhutan. For example, Bangladesh could renegotiate transit and transshipment issues with India for a permanent settlement of the transboundary river issues on the basis of fairness and collaboration. The GBM region has a long history and tradition shared by people in all co-riparian countries, and we should use the natural flow of rivers as a thread to bind us rather than as a cause for concern.

Key Points

- Bangladesh’s survival depends on fair, basin-wide management of transboundary rivers originating upstream.

- The Ganges Water Sharing Treaty is limited, inconsistently implemented, and expires in 2026.

- Reduced dry-season flows have caused severe economic loss, salinity, ecological damage, and displacement.

- Integrated basin-scale compacts, not narrow treaties, offer sustainable benefits for all co-riparian states.

- Bangladesh must prioritise hydro-diplomacy and ratify international water law frameworks.

Md. Khalequzzaman is a Professor of Geology at Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania, USA. He can be contacted at mkhalequ@commonwealthu.edu

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.