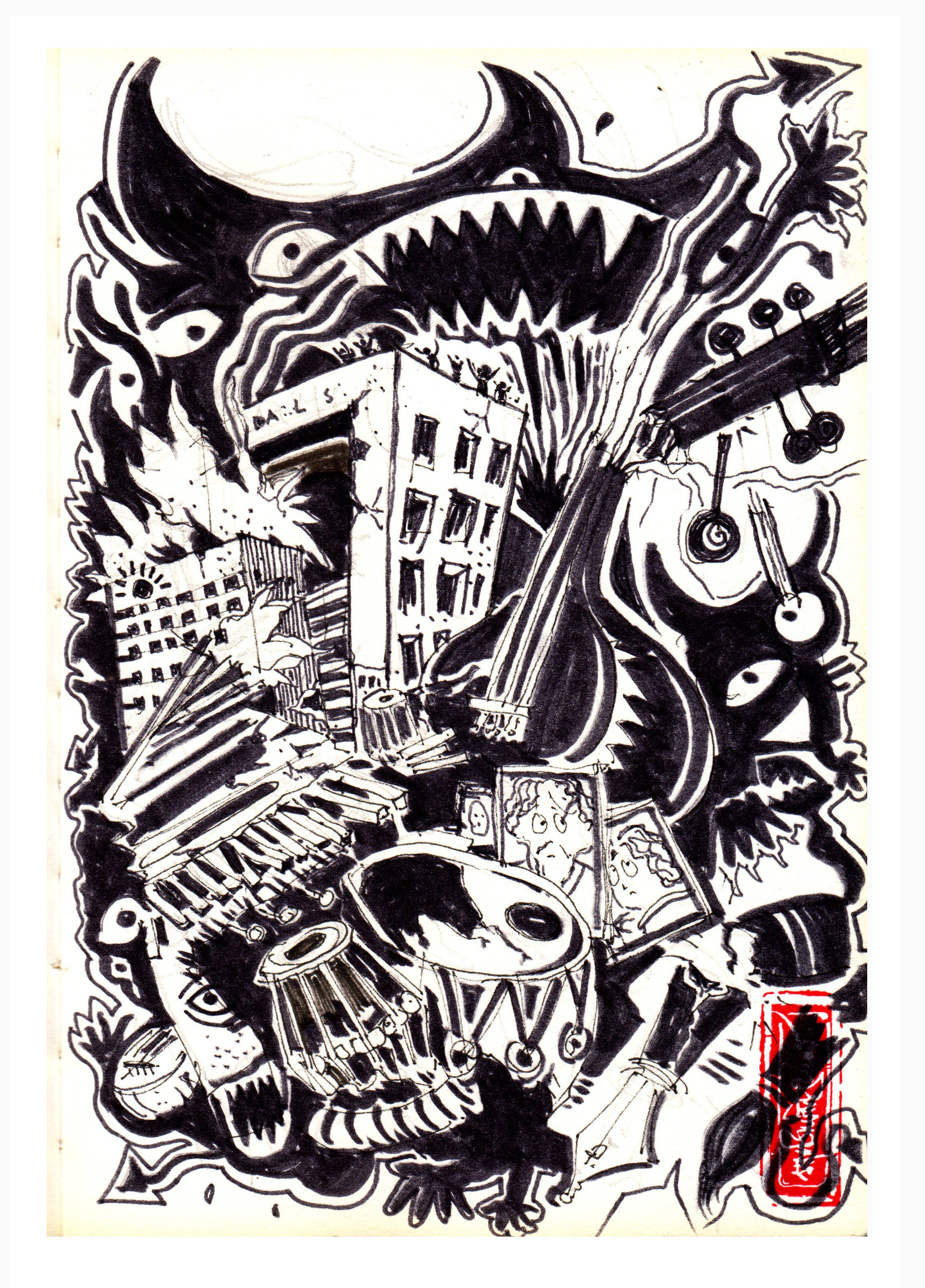

Vandalism and the death of civilisation

Vandalism is not merely the destruction of physical objects; it is an assault on memory, identity, and the accumulated intelligence of civilisation. Throughout history, architecture has functioned as a visible repository of cultural DNA encoding political authority, social order, belief systems, and technological mastery. When vandalism strikes architecture, it erases far more than bricks and stones; it disrupts historical continuity and fractures collective identity. This article critically examines vandalism as a socio-political phenomenon, distinguishing it from protest and resistance, and tracing its impact across Western, European, and South Asian civilisations, with a focused lens on Bengal’s deltaic history. From ancient and medieval periods to colonial and post-independence Bangladesh, the article argues that vandalism operates as a “cultural bacterium” that consumes the DNA of nations. Finally, it questions whether contemporary Bangladesh is entering a dangerous crossover zone of normalised vandalism and outlines pathways for prevention, governance reform, and cultural resistance.

What is vandalism? Defining the term beyond casual destruction

Vandalism, in its classical definition, refers to the deliberate destruction or defacement of property without the consent of the owner. However, when applied to architecture and urban environments, vandalism transcends criminal mischief—it becomes a political, cultural, and psychological act. The term itself derives from the Vandals, a Germanic tribe blamed (perhaps unfairly) for the sack of Rome in 455 CE, an event that later historians mythologised as the collapse of classical civilisation.

Crucially, vandalism must be distinguished from legitimate protest. Protest challenges power through symbolic acts and dialogue; vandalism annihilates symbols to erase history altogether. Mob violence and vandalism often overlap, but they are not identical. Mob violence may erupt spontaneously, while vandalism often involves intentional targeting of symbolic structures, monuments, places of worship, and institutions of memory selected precisely because of what they represent.

Architecture becomes the primary victim because it is the most visible, most durable, and most symbolic form of cultural expression.

Architecture as civilisational DNA

Architecture is not neutral. Cities, monuments, religious structures, and civic buildings encode what can be called the DNA of civilisation—political authority, economic systems, cosmology, technological capacity, and collective aspirations. When this architectural DNA is destroyed, societies lose their capacity to remember themselves.

Vandalism thus functions like a cultural bacterium: it does not merely damage the host, it consumes the genetic code that enables regeneration. Once erased, architectural memory is rarely recoverable in its original form.

Vandalism across Western and European civilisations

European history offers abundant evidence of how regime change frequently translates into architectural annihilation.

From the late Roman Empire through the early Middle Ages, temples, forums, and statues were systematically dismantled, sometimes for ideological reasons, sometimes for building materials. Christianisation led to the destruction or conversion of pagan structures, redefining sacred space through erasure.

During the French Revolution, vandalism was almost institutionalised. Royal statues were decapitated, churches desecrated, and palaces stripped. Ironically, the modern concept of “heritage preservation” emerged because of this destruction, as scholars like Abbé Grégoire first warned against “vandalism” as a crime against national memory.

Political upheavals, wartime bombing, and ideological iconoclasm reshaped cities irreversibly. While post-war reconstruction restored functionality, much historical authenticity was permanently lost (Glendinning, 2013).

In all these cases, vandalism accompanied power transition, where the incoming regime sought legitimacy by annihilating the physical reminders of its predecessor.

Vandalism in the Subcontinent and Southeast Asia

The subcontinent experienced layered vandalism across centuries —religious, imperial, and colonial. Invasion-era destruction of temples, Buddhist monasteries, and urban centers was often strategic rather than chaotic. In later periods, colonial restructuring erased indigenous urban logic in favour of administrative convenience.

Southeast Asia similarly witnessed the neglect and destruction of Angkorian, Pagan, and Majapahit structures, not always through violence, but through institutional abandonment, which is another silent form of vandalism.

Vandalism beyond Bengal: Lessons from South and Southeast Asia

Vandalism in South and Southeast Asia rarely manifests as isolated criminality; instead, it emerges at the intersection of political transition, ideological assertion, ethnic tension, and state fragility. Across Thailand, Myanmar, Vietnam, and India, architecture, particularly religious and historic structures, have repeatedly become the first casualty during moments of upheaval. These cases offer critical parallels to Bengal’s experience, revealing that vandalism is not region-specific but structurally produced within transitional societies.

Thailand: Political flux and symbolic damage

Thailand’s architectural vandalism is closely tied to cycles of political instability, military coups, and contested national narratives. While the country is globally admired for its heritage conservation, periods of unrest, especially during pro- and anti-monarchy movements, have seen symbolic defacement of public buildings, statues, and historic precincts in Bangkok and regional centres.

Notably, vandalism here is often performative rather than annihilative. Graffiti on monuments, damage to civic architecture, and symbolic occupation of historic sites function as spatial claims over political legitimacy. Temples themselves are rarely destroyed, but their surrounding urban fabric and ceremonial landscapes are frequently disrupted, reflecting a tension between sacred continuity and modern political dissent.

Vandalism does not always seek total destruction, sometimes it seeks symbolic visibility, turning architecture into a political stage.

Myanmar: Militarisation and erasure of plural heritage

Myanmar presents one of the most severe contemporary examples of architectural vandalism driven by state violence and ethnic conflict. Here, vandalism operates on two levels:

1. Targeted destruction by armed actors, and

2. Systematic neglect enforced through displacement.

In regions affected by ethnic and religious tension, Buddhist, Christian, and Muslim architectural sites alike have suffered damage or abandonment. The destruction of religious buildings is often framed as collateral damage, but spatial analysis reveals strategic erasure of minority cultural markers.

In Myanmar, vandalism is inseparable from militarisation. Architecture becomes a silent victim of power assertion, where destroying or abandoning structures helps reconfigure territorial control. This resonates strongly with Bengal’s post-partition experience, where architecture lost custodianship due to displacement rather than direct attack.

Vietnam: Ideological rewriting and revolutionary vandalism

Vietnam’s experience of vandalism is deeply rooted in revolutionary ideology and post-war reconstruction. During the mid-20th century, colonial-era buildings, religious structures, and traditional settlements were frequently demolished or altered, not always violently, but deliberately to erase symbols of foreign domination and feudal hierarchy.

In many cases, historic architecture was sacrificed in favour of new socialist urban forms, justified as progress. This introduces a critical form of vandalism: ideological demolition, where destruction is legitimised by a future-oriented narrative.

However, Vietnam also demonstrates a later corrective phase, where lost heritage triggered renewed conservation consciousness.

India: Mob violence, religious polarisation, and architectural targeting

India provides perhaps the most widely documented cases of mob-driven architectural vandalism, often linked to communal tension and identity politics. Religious structures temples, mosques, shrines, and historic urban precincts have repeatedly been targeted not for their architectural value, but for what they are made to represent.

Here, vandalism is deeply narrative-driven. Architecture becomes a proxy for historical grievance, reduced to a single identity marker. Once labelled as “other,” even centuries-old structures lose their protection as cultural heritage.

Importantly, India also shows how legal ambiguity and delayed justice contribute to the normalisation of vandalism. When accountability remains unresolved, destruction enters public memory as precedent rather than exception.

This is directly relevant to Bengal and Bangladesh, where similar risks exist if heritage protection becomes selectively enforced.

Sri Lanka: Civil War, memory loss, and the weaponisation of sacred architecture

Sri Lanka presents one of the most complex and instructive cases of vandalism in South Asia, where prolonged civil conflict transformed architecture into both a symbolic and strategic target. Unlike sudden outbreaks of mob violence, vandalism in Sri Lanka unfolded gradually over decades, shaped by ethnic tension, militarisation, and contested narratives of nationhood.

During the civil war (1983–2009), architectural destruction occurred through multiple mechanisms. Religious structures Buddhist, Hindu, Christian, and Islamic were damaged, abandoned, or repurposed, not always because of their faith identity, but because of their territorial and symbolic presence. Temples, kovils, and mosques often functioned as landmarks of cultural belonging; once conflict intensified, these same landmarks became liabilities. Their destruction or occupation signalled control over space rather than theological hostility.

A critical dimension of Sri Lankan vandalism is state and non-state symmetry. Unlike classical invasions, both insurgent groups and state forces contributed to architectural loss, sometimes directly through shelling, sometimes indirectly through prolonged neglect and displacement. Entire historic settlements were emptied, leaving architecture without custodians. This abandonment constitutes a silent but irreversible form of vandalism, where buildings decay not through attack but through enforced absence.

Post-war reconstruction in Sri Lanka further complicates the narrative. In several cases, rebuilding prioritised political symbolism over historical accuracy, resulting in spatial rewriting rather than restoration. Older layers—colonial, Tamil, Muslim, or syncretic—were often marginalised in favour of dominant national narratives. This introduces a form of post-conflict ideological vandalism, where memory is reshaped not by mobs but by planning decisions.

Vandalism does not end with violence; it often continues in peace through selective remembrance and spatial reconfiguration.

Bengal: A delta repeatedly scarred by vandalism

Bengal’s architectural fragility is not accidental; it is structurally produced by geography, material culture, and political volatility. Unlike stone-based civilisations, Bengal relied overwhelmingly on baked brick, lime mortar, and timber, making its architecture inherently recyclable and therefore perpetually vulnerable to vandalism, appropriation, and erasure.

More critically, Bengal’s history is marked by frequent regime discontinuity without cultural succession. Each political transition rather than assimilating previous layers often attempted to erase them.

Erasure through reuse

The decline of Buddhist Bengal is often simplistically attributed to “religious change.” Archaeological evidence, however, reveals a more unsettling process: systematic dismantling and reuse, not sudden destruction.

At Somapura Mahavihara (Paharpur), excavations show that large portions of the monastery were quarried in later centuries for brick reuse in nearby rural settlements. This was not an act of hostility but of cultural amnesia a form of functional vandalism. The monastery ceased to be understood as a sacred institutional complex and was reduced to a convenient brick quarry.

Similarly, at Mainamati, structural scars indicate repeated phases of dismantling. Walls were selectively broken, not collapsed, suggesting deliberate extraction. This reflects a moment when institutional memory dissolved, and architecture lost its semantic value.

Adaptive survival and selective erasure

Unlike North India, Bengal’s Islamisation was relatively gradual. Many early Sultanate mosques incorporated spolia pillars, bricks, and foundations from pre-Islamic structures. While often cited as evidence of tolerance or pragmatism, this also represents architectural displacement.

Certain Buddhist and Hindu sites were not destroyed violently but were absorbed, overwritten, and anonymised. Their identities vanished even as their materials survived.

At sites like Gaur and Pandua, shifts in capital resulted in rapid abandonment. Palaces, madrasas, and mosques were stripped for materials within decades. Political instability created orphaned architecture, which rarely survives long in the Bengal delta.

Monumentality and Internal Decay

The Mughal period introduced architectural grandeur forts, gardens, tombs yet it also institutionalised a paradox: architecture as state propaganda. Buildings symbolised authority rather than community.

When Mughal power declined, these symbols became liabilities. Structures like Lalbagh Fort remained unfinished not due to technical incapacity, but because political legitimacy collapsed mid-construction. An unfinished monument is a vulnerable monument; it invites neglect, misuse, and reinterpretation.

Later, many Mughal structures were cannibalised during regional conflicts and early colonial occupation. Their destruction was rarely documented because it occurred through bureaucratic indifference, not spectacle.

Vandalism by planning

Colonial vandalism in Bengal was neither emotional nor chaotic it was administrative.

British urban restructuring systematically erased indigenous spatial systems. Mughal canals were filled, ceremonial routes disrupted, and organic neighbourhoods fractured by grid-based planning. This was not destruction in the visual sense, but it dismantled urban intelligence accumulated over centuries.

Railway construction in the 19th century caused extensive damage to archaeological mounds across Bengal. Ancient sites were levelled not out of malice, but because they were seen as topographical inconveniences.

This introduces a critical concept: bureaucratic vandalism is often more permanent than violent vandalism.

Internalised vandalism

Partition (1947) marks a psychological rupture. Massive displacement turned architecture into abandoned property, stripping buildings of custodianship. Many zamindar houses, temples, mosques, and civic buildings entered a liminal state neither protected nor used.

After independence (1971), a new and dangerous phenomenon emerged: ideological vandalism from within. Architecture became hostage to political rivalry. Monuments were attacked not because they belonged to “others,” but because they symbolised inconvenient narratives.

This phase of vandalism is historically distinct because the agents of destruction are no longer external invaders or conquering forces, but citizens acting against their own collective inheritance. Unlike earlier epochs, where architectural loss could be attributed to war, invasion, or imperial transition, contemporary vandalism unfolds from within society itself. The vandals are socially embedded actors often mobilised along partisan, ideological, or opportunistic lines who share language, territory, and citizenship with the very culture they damage. This internalisation marks a critical rupture: destruction is no longer imposed upon a society but enacted by it, signaling a deep fracture in civic consciousness and a weakening of shared ownership over national heritage.

Equally significant is the shift in targets. In this phase, vandalism is directed not at foreign symbols or imposed authorities, but at national monuments, public institutions, and shared cultural landmarks. These sites memorials, sculptures, historic buildings, and civic spaces embody collective memory and statehood. Their attack represents not resistance to occupation, but a symbolic rejection of inconvenient narratives embedded in the built environment. Architecture here becomes a proxy battlefield where political contestation plays out through spatial erasure rather than dialogue, undermining the very foundations of national continuity.

Most critically, the motivation behind such acts is no longer rooted in doctrinal belief, religious iconoclasm, or cultural opposition. Instead, it is driven by political visibility and performative power. Vandalism becomes a spectacle designed to attract attention, dominate media cycles, and demonstrate control over public space. In this context, destruction functions as a language of intimidation and announcement rather than conviction. The act itself matters more than the meaning of the object destroyed.

This is, therefore, vandalism as performance, a choreographed expression of dominance amplified by mob psychology and accelerated by social media circulation. The presence of cameras, instant sharing, and algorithmic visibility transforms vandalism into a public ritual, where destruction is validated through virality. Individual accountability dissolves within the crowd, while digital reproduction ensures that the symbolic damage far outlasts the physical act. In such conditions, architecture becomes a stage, not a victim alone, and vandalism evolves into a recurring political tool one that normalises cultural erasure and destabilises the ethical boundaries of civic life.

How do vandals form? The social chemistry of destruction

Vandal groups rarely emerge as spontaneous or irrational mobs; rather, they are produced through a discernible social chemistry in which psychological conditioning, political narrative, and institutional failure interact over time. The first stage in this process is narrative simplification, where complex histories, layered identities, and nuanced political realities are reduced to easily recognisable enemy symbols.

Architecture monuments, buildings, statues, and institutions becomes especially vulnerable at this stage because it embodies historical continuity in visible form. Once reduced to a single, oversimplified meaning, these structures are stripped of their cultural depth and recast as obstacles to a newly constructed narrative.

The second stage involves moral disengagement, a psychological mechanism through which acts of destruction are reframed as morally justified or even necessary. Vandalism is no longer perceived as a crime but as an act of correction, resistance, or justice. Through ideological rhetoric, historical grievance real or imagined is mobilised to legitimise physical damage. At this point, ethical boundaries collapse: destroying architecture is no longer seen as harming society, but as purifying it. This moral inversion is particularly dangerous because it replaces critical thinking with emotional certainty.

The third condition enabling vandalism is anonymity through numbers. When individuals act within a crowd, personal responsibility dissolves into collective action. The mob provides both physical cover and psychological insulation, allowing participants to commit acts they would otherwise reject individually. In such settings, accountability is diffused, and violence becomes self-reinforcing. The crowd transforms into a temporary authority, overpowering legal, ethical, and civic restraints through sheer presence.

The final and most decisive factor is institutional silence. When law enforcement hesitates, judicial processes stall, or political leadership remains ambiguous, vandalism enters a feedback loop. Each unpunished act becomes a precedent, signaling social permission for repetition. As Goldstein (2016) observes, vandalism flourishes precisely where ideological momentum accelerates faster than institutional response. In these conditions, architecture becomes the safest and most convenient target: it cannot resist, negotiate, or flee. Silent and immobile, the built environment absorbs the aggression of society, becoming the first casualty in a broader collapse of civic order and collective responsibility.

Is Bangladesh crossing into normalised vandalism?

The question of whether Bangladesh is crossing into a phase of normalised vandalism must be approached with caution, neutrality, and historical awareness. Normalisation does not occur suddenly; it develops gradually when acts of destruction become predictable, follow recognisable political or social patterns, and recur at moments of transition or tension. When vandalism can be anticipated during political changeovers, public unrest, or ideological confrontation, it ceases to be an exception and begins to function as an expected outcome. This predictability weakens public alarm and erodes the collective sense that such acts are extraordinary or unacceptable.

A further warning sign emerges when vandalism becomes politically excusable. This occurs not necessarily through formal endorsement, but through selective silence, delayed response, or narrative justification from influential actors. When destructive acts are contextualised as “understandable reactions,” “inevitable expressions,” or secondary to political objectives, the boundary between dissent and damage becomes blurred. In such an environment, accountability is diluted, and the ethical clarity needed to protect shared spaces and heritage is gradually lost.

Equally critical is the point at which vandalism becomes socially tolerated. Social tolerance does not imply active support; rather, it manifests as resignation, indifference, or fatigue within the public sphere. When repeated incidents no longer provoke collective outrage, debate, or demand for redress, destruction loses its shock value. Instead, it becomes a grim signal marking the rhythms of political cycles an anticipated disruption rather than a societal rupture.

Historical experience across societies suggests that once vandalism is normalised at the level of monuments and symbols, it rarely remains confined there. The erosion of respect for shared physical heritage often precedes broader institutional weakening, gradually extending from buildings to systems, and from symbolic targets to human ones. This progression underscores why vigilance is essential: not to sensationalise isolated events, but to recognise patterns early and reaffirm the principles of civic responsibility, lawful dissent, and collective ownership of the nation’s cultural and institutional foundations.

Vandalism as civilisational suicide

Civilisations rarely disappear solely because of external invasion or military defeat; more often, they unravel when they lose the internal capacity to protect, interpret, and transmit their own memory. This process is subtle and cumulative. When societies cease to recognise the value of their inherited spaces cities, monuments, religious structures, civic buildings, they begin to sever the tangible links between past experience and present identity. In this sense, vandalism is not merely an act of physical destruction but a form of civilisational self-harm, eroding the foundations upon which continuity is built.

Architecture occupies a central position in this process because it functions as a civilisational archive written in space. Unlike texts or oral traditions, architecture endures through everyday presence; it silently educates, reminding societies of their origins, struggles, and aspirations. When architectural fabric is repeatedly vandalised, neglected, or politicised, that archive becomes fragmented. A nation then risks losing not only verifiable traces of its past but also its imaginative horizon the ability to envision a future rooted in historical confidence rather than perpetual rupture. The destruction of built heritage thus produces a temporal dislocation, where societies exist in a permanent present, detached from both memory and long-term vision.

Preventing vandalism: Beyond policing

Addressing vandalism cannot rely solely on surveillance, policing, or punitive measures. While law enforcement is essential, it is insufficient without deeper cultural and institutional reinforcement. Sustainable prevention begins with architectural literacy within education, enabling citizens to understand buildings not as inert objects but as repositories of collective knowledge, labour, and ethical value. When people can read architecture, they are less likely to accept its destruction as inconsequential.

Equally important is the legal recognition of heritage as a public trust, rather than as the symbolic property of shifting political regimes. Such recognition establishes clear responsibility, continuity of care, and legal consequences that transcend electoral cycles. This must be supported by a broad political consensus on cultural immunity, where heritage sites, monuments, and public architecture are collectively acknowledged as beyond partisan contestation. Without this consensus, architecture remains vulnerable to being weaponised during moments of political tension.

Finally, effective prevention depends on community-based guardianship of architectural sites. When local communities perceive heritage as shared ownership rather than distant authority, protection becomes participatory rather than imposed. A society that understands, values, and claims its architecture is significantly harder to manipulate, because its cultural anchors resist both ideological simplification and opportunistic destruction.

Vandalism is never solely about broken walls or damaged monuments; it is about erasing alternatives, silencing memory, and asserting dominance through fear and visibility. Across history, civilisations that tolerated repeated acts of vandalism whether through indifference, justification, or selective silence inevitably weakened themselves from within. The loss begins in stone and brick, but it does not end there; it extends into institutions, social trust, and civic ethics.

For Bengal, whose architectural heritage is already fragile due to its deltaic ecology and layered history of transition, the cost of such amnesia is particularly high. To protect architecture is not to preserve nostalgia; it is to safeguard the intellectual, cultural, and moral continuity of the nation. In this sense, defending the built environment is inseparable from defending the soul of the society itself.

References

Choay, F. (2001). The invention of the historic monument. Cambridge University Press.

Chattopadhyay, S. (2005). Representing Calcutta: Modernity, nationalism, and the colonial uncanny. Routledge.

Cohen, S. (1973). Property destruction: Motives and meanings. Political Science Quarterly, 88(1), 23–45.

Glendinning, M. (2013). The conservation movement: A history of architectural preservation. Routledge.

Goldstein, A. P. (2016). The psychology of vandalism. Springer.

Merrills, A. (2010). History and geography in late antiquity. Cambridge University Press.

Metcalf, T. R. (1989). An imperial vision: Indian architecture and Britain’s Raj. University of California Press.

Morrison, K. D. (2015). Trade, urbanism, and agricultural expansion in South Asia. Oxford University Press.

Stanley, J. (2018). How fascism works: The politics of us and them. Random House.

Vale, L. J. (2014). Architecture, power, and national identity. Routledge.

Ward-Perkins, B. (2005). The fall of Rome and the end of civilisation. Oxford University Press.

Sajid Bin Doza, PhD, is an art and architectural historian, heritage illustrator, and cultural cartoonist. He is an Associate Professor in the Department of Architecture, School of Architecture and Design (SoAD), BRAC University. He can be reached at sajid.bindoza@bracu.ac.bd.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.