Before the Assam–Bengal line system: Mobility, land, and belonging

This is the opening instalment of a multi-part series on the Assam–Bengal Line System: How land policies shaped modern Bangladesh.

A region without hard edges

Long before colonial officials drew “lines” across maps of Assam, Sylhet, and Bengal, the region lived by a different grammar of space. Rivers, forests, hills, and seasonal rhythms mattered far more than borders. People moved with floods, with harvests, with trade routes, and with political change. Identities were layered and situational—village, occupation, language, faith—rarely reduced to a single label.

This matters because the Line System, introduced in the early 1920s, is often treated as a response to an age-old problem of migration. It was not. It was a solution invented for a problem the colonial state itself helped create. To understand how that happened, we must begin before British rule reshaped land, law, and belonging.

This first article sets the ground beneath the later conflict. It shows that movement between Bengal and Assam was neither new nor inherently destabilising. What changed was not mobility itself, but the meaning attached to it.

The geography that encouraged movement

The eastern subcontinent is one of the most fluid ecological zones in the world. The Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna river system creates a constantly shifting landscape of floodplains, chars (river islands), wetlands, and forest clearings. Land appears and disappears within a generation. Fields are washed away; new soil emerges downstream. Survival has always required flexibility.

In such an environment, movement was not an exception—it was an adaptation. Peasant households relocated when rivers changed course. Fishing communities followed water. Cultivators expanded into newly deposited alluvial land. These movements did not register as “migration” in a modern sense; they were simply life within a deltaic world.

Assam’s Brahmaputra Valley, sparsely populated compared to Bengal’s dense delta, was part of this shared ecological system. The river connected the two regions more than it divided them. Boats, not borders, shaped interaction.

Pre-colonial Assam: Land, power, and flexibility

Before British conquest, Assam was ruled for centuries by the Ahom kingdom. The Ahoms governed through a system that prioritised labour and allegiance rather than rigid territorial ownership. Land was abundant relative to population, and control over people mattered more than control over fixed plots.

The paik system organised households into units responsible for state service—military, agricultural, or artisanal. Rights to cultivate land were linked to participation in this system, not to permanent private ownership. Crucially, people could be absorbed into the polity over time. Ethnic and cultural boundaries were porous; groups assimilated through language, intermarriage, and service.

This did not mean Assam was conflict-free. It did mean, however, that belonging was negotiated socially, not enforced bureaucratically. There was no concept of an “outsider” as a permanent legal category.

Sylhet: A cultural bridge, not a borderland

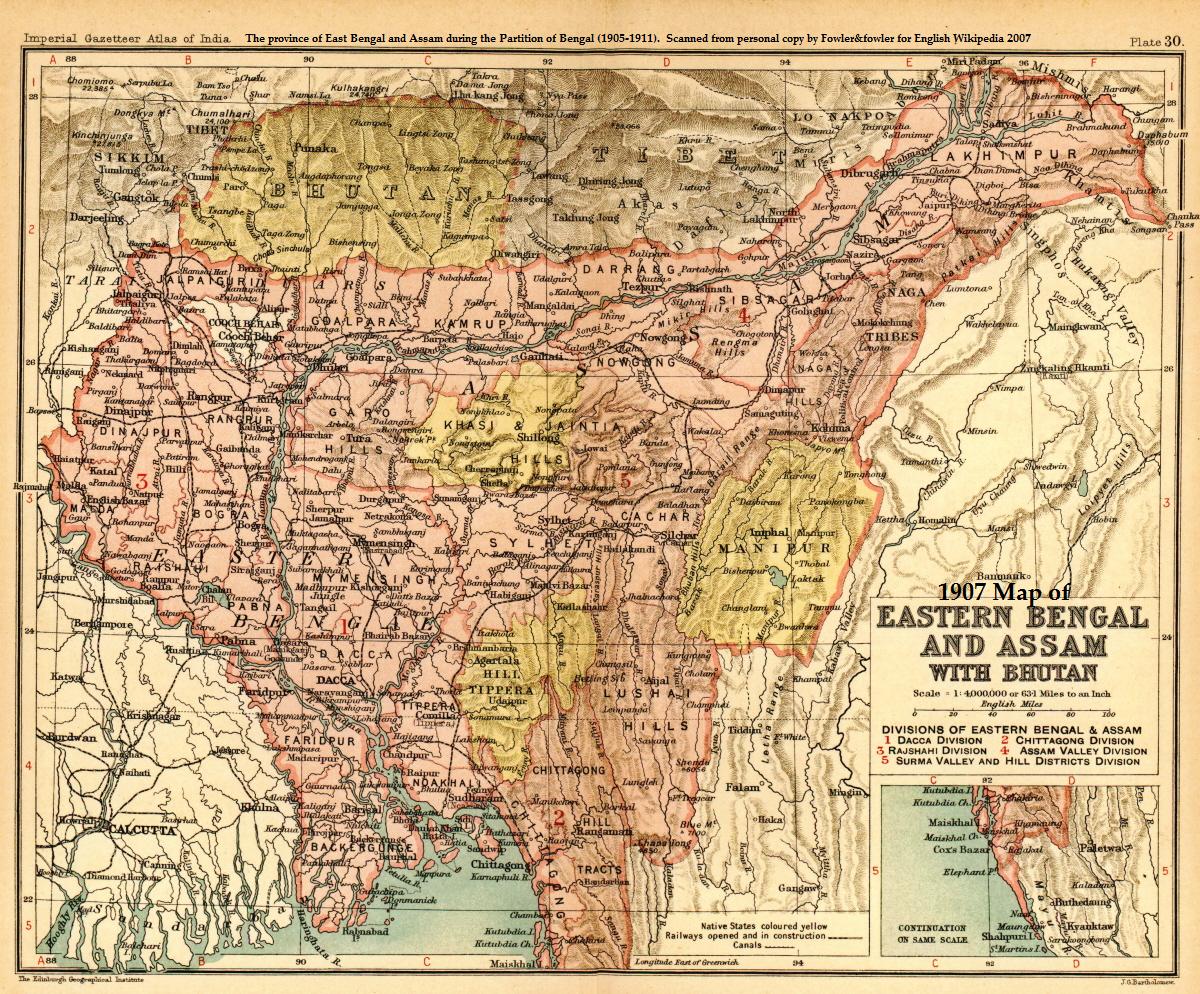

Sylhet occupies a special place in this history. Culturally and linguistically tied to Bengal, yet politically attached to Assam for long periods, Sylhet functioned as a bridge rather than a frontier.

Trade routes connected Sylhet to the Brahmaputra Valley. Religious networks—particularly Sufi shrines—linked communities across regions. Seasonal labour moved back and forth. These connections normalised mobility and blurred distinctions between “Assamese” and “Bengali” long before those identities hardened. Later colonial decisions would turn Sylhet into a fault line. Before that, however, it exemplified coexistence through circulation rather than separation.

Éva Rozália Hölzle, in her paper published in the Asian Journal of Social Science (Brill), “The Formation of the Sylhet–Meghalaya–Assam Border”, notes that the contemporary borderline between Sylhet, Meghalaya, and Assam gradually came into being as a result of long socio-political transformations (Ludden, 2003). During the Mughal era, Sylhet constituted the Empire’s eastern frontier, while it served as the western frontier for the kingdoms of Assam. Nevertheless, there is no historical evidence that “a definite Sylhet region” (Ludden, 2003) existed prior to the Mughal conquest. The area included different territories of the Khasis, Garos, Bengali Hindus, and Muslims—a population composition that characterises Sylhet even today (Ludden, 2003).

The border between Meghalaya and Sylhet was a direct result of British expansion and the desire to impose stricter governance of population movements from the north, with the objective of protecting British imperial interests in Bengal (Ludden, 2003). The additional Assam–Sylhet borderline was also the result of a longer socio-political transformation process between 1826 and 1947 (Chakrabarty, 2002).

Bengal before the British: Abundance and adaptation

Pre-colonial Bengal was one of the most agriculturally productive regions in the world. Its prosperity rested on wet-rice cultivation, artisanal production, and riverine trade. Yet abundance did not mean stability. Floods, crop failures, and political upheavals periodically displaced people.

Importantly, these movements were absorbed within a flexible agrarian system. Land was cleared as the population grew; forests were converted into fields; new settlements formed on fresh alluvium. Mobility did not threaten social order—it sustained it. This balance would be disrupted when colonial rule redefined land as a taxable commodity rather than a shared resource.

How the British reframed land and people

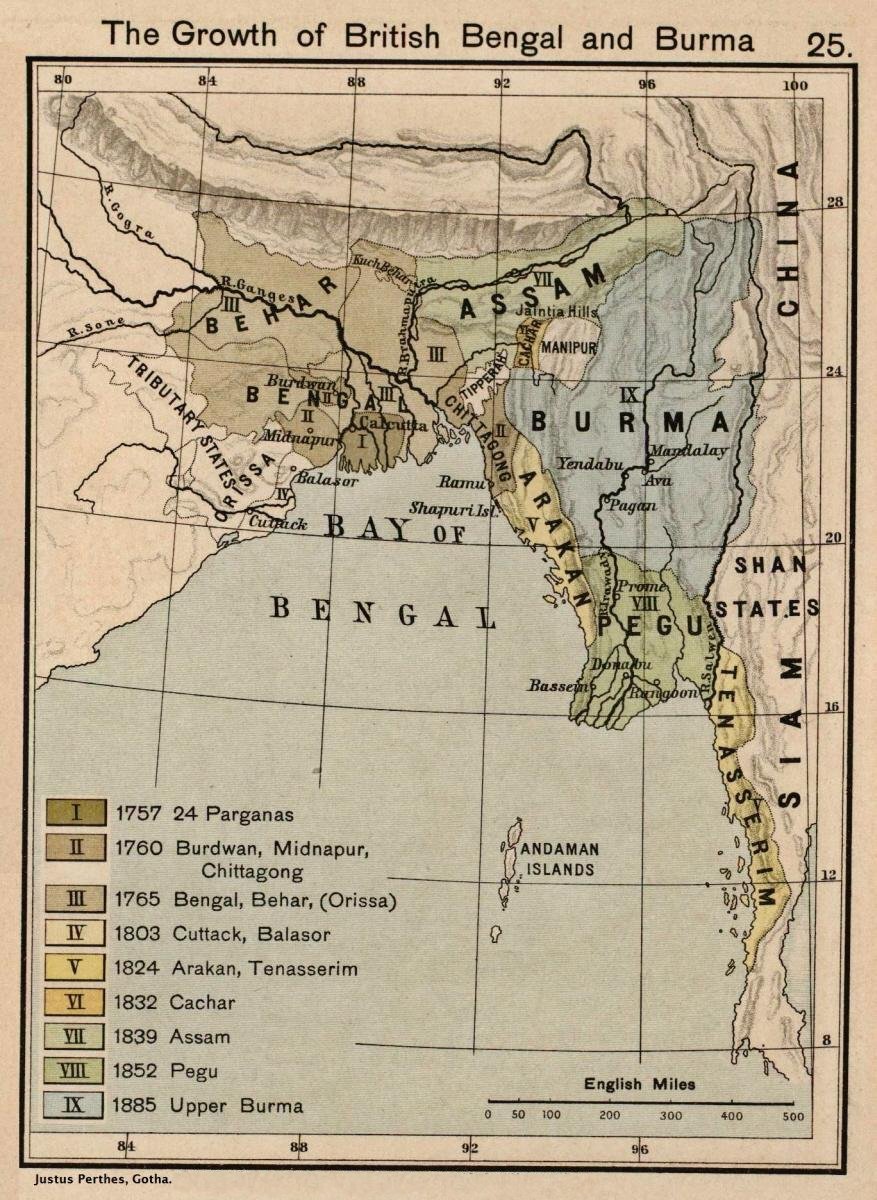

When the British East India Company gained revenue control over Bengal in the mid-18th century, it brought with it a radically different vision of land. Revenue had to be predictable. Ownership had to be legible. Populations had to be counted, classified, and fixed.

This shift culminated in policies such as the Permanent Settlement, which transformed land into private property and tied revenue demands to it. Over time, this created land scarcity, indebtedness, and displacement—especially in the densely populated districts of eastern Bengal.

At the same time, regions such as Assam were increasingly viewed through an extractive lens. Forests became resources; uncultivated land became “waste.” The stage was set for a new logic: moving people to maximise revenue. Crucially, the colonial state began to see mobility not as normal, but as something to be managed.

Census, categories, and the birth of anxiety

One of the most consequential colonial innovations was the census. Beginning in the late 19th century, the British attempted to classify every individual by religion, language, and ethnicity.

These categories froze identities that had once been fluid. They also made demographic change visible—and therefore political. When numbers shifted, alarm followed. Before this, no authority had asked how many people spoke which language in a district, or what proportion followed which faith. Once these questions were institutionalised, population itself became a source of fear. This marks a critical turning point. Migration did not suddenly increase because of inherent cultural traits; it became controversial because it became countable.

Rethinking “indigenous” and “migrant”

In the pre-colonial world, these categories had little meaning. A family that settled, cultivated, paid dues, and integrated over time became part of the local order.

Colonial rule reversed this logic. Belonging began to depend on origin rather than participation. Time ceased to soften difference. Instead, it hardened it. This redefinition would later underpin the Line System, which attempted to spatially separate people based on where they were assumed to come from—regardless of how long they had lived there.

Land, authority, and belonging in the pre-colonial order

To understand why mobility was not inherently destabilising before British rule, it is necessary to look more closely at how land and authority functioned in both Bengal and Assam prior to colonial intervention. As historians such as Ranajit Guha have shown in A Rule of Property for Bengal, pre-colonial agrarian systems did not treat land as a fully alienable commodity in the modern sense. Rights over land were layered, overlapping, and often conditional, tied to cultivation, tribute, and political loyalty rather than absolute ownership.

Further, the work provides an intellectual history of the Permanent Settlement of Bengal (1793), showing that it was not an inevitable administrative choice but the product of an eighteenth-century European intellectual genealogy, particularly physiocratic thought, adapted to Bengal’s agrarian context. British policymakers, influenced by thinkers such as Alexander Dow, Henry Pattullo, and Philip Francis, aimed to create secure property rights to incentivise agricultural improvement. Yet, when these ideas were transposed onto Bengal’s pre-colonial, flexible land and revenue systems, they produced an “epistemological paradox”. Rather than fostering capitalist agriculture, these policies reinforced neo-feudal land relations, embedded pre-capitalist social hierarchies within colonial governance, and demonstrated how colonial policy operated as both knowledge production and statecraft—translating abstract European theories into concrete legal, fiscal, and social structures that reshaped land, authority, and belonging in ways that often contradicted their intended effects. The British intended the Permanent Settlement to create capitalist farming and secure revenue, but instead it reinforced landlord power and limited peasants’ rights.

In Mughal Bengal, sovereignty rested on the ability to extract revenue, not on enforcing fixed village boundaries or exclusive property titles. Peasants cultivated land under a variety of tenurial arrangements, and new cultivation was actively encouraged as forests were cleared and wetlands reclaimed. Richard Eaton’s work on the eastern Bengal frontier, in his book The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, demonstrates that agricultural expansion was a centuries-long process, driven by riverine ecology and state encouragement rather than sudden population explosions. Movement into new lands was therefore understood as productive, even desirable.

Early environmental and agrarian foundations (2nd millennium B.C.–5th century B.C.)

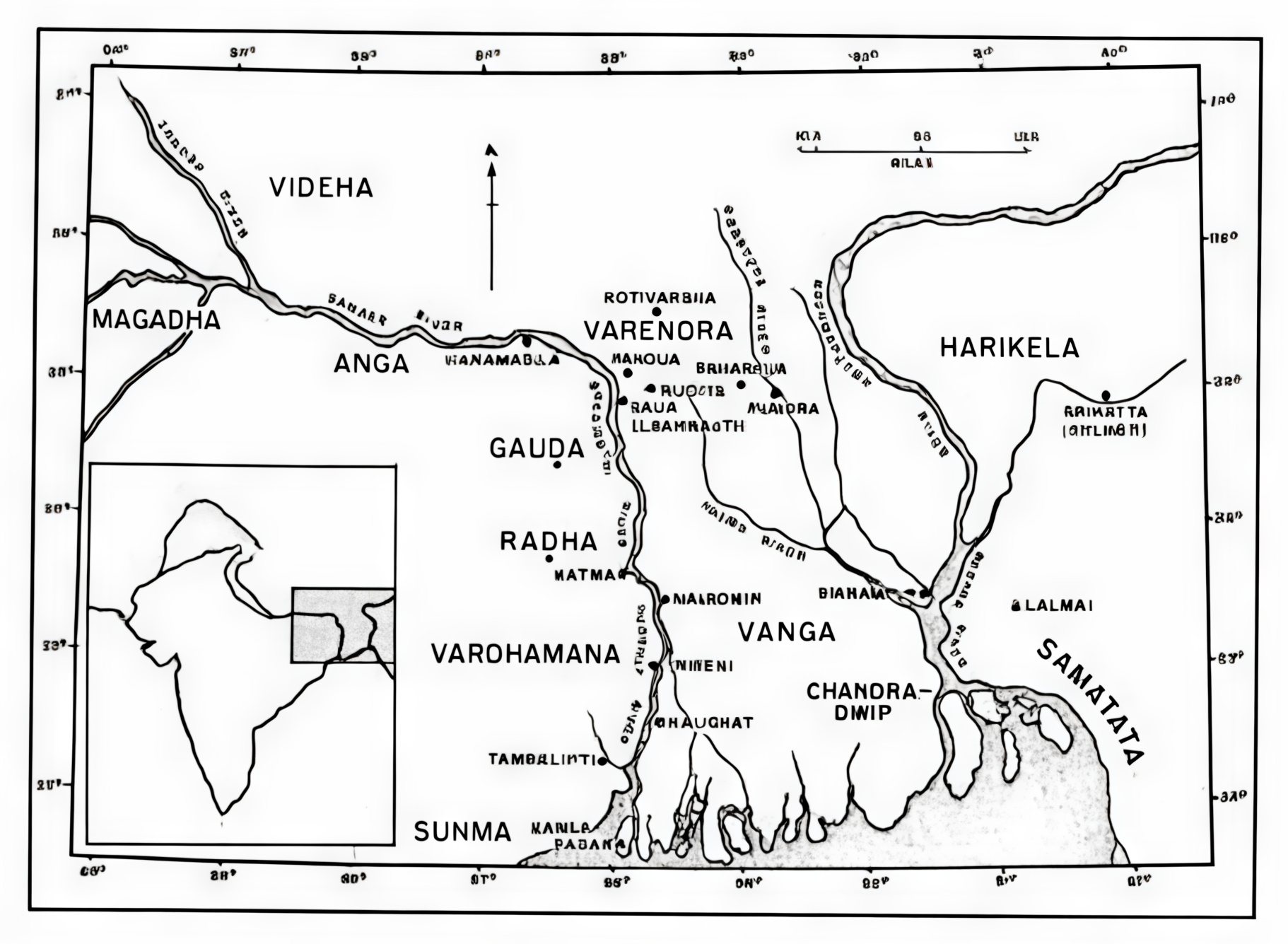

The Bengal delta, a flat, low-lying floodplain shaped by the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers, has been built up over millennia. Rivers served as transport routes and defined cultural subregions: Varendra, Bhagirathi–Hooghly, Vanga, Samatata, and Harikela. Human settlement dates back to the second millennium B.C., with tribes such as the Pundra, Raḍha, Suhma, and Vanga lending their names to regions. Archaeological evidence shows rice cultivation, systematic housing, cemeteries, and copper ornaments. Early agriculture involved shifting cultivation, using stone tools for rice and millet farming. Proto-Munda speakers may have pioneered these systems around 1500 B.C. By the sixth–fifth centuries B.C., the middle Gangetic Plain had shifted to permanent wet-rice farming, requiring communal labour, irrigation, and improved tools such as iron axes and ploughshares, marking the transition to advanced rice agriculture and laying the foundation for Bengal’s agrarian society.

Fourteenth–fifteenth centuries: Forest clearing, pīrs, and agrarian expansion

From the fourteenth century onward, the expansion of cultivation in Bengal’s forested frontiers became closely linked to charismatic Muslim holy men (pīrs), who were remembered not only as spiritual authorities but also as organisers of agrarian settlement. Oral traditions, gazetteers, and literary works such as Mukundaram’s Caṇḍī-Maṅgala and the Sekaśubhodayā depict them guiding large local and migrant populations in clearing jungle, embanking land, digging tanks, establishing wet-rice cultivation, building mosques, and founding villages, often with state backing. In this way, religious charisma, agrarian expansion, and the institutionalisation of Islam became mutually reinforcing and eventually produced a rural “religious gentry”. A closely related narrative surrounds Khan Jahan (d. 1459), the patron saint of Bagerhat on the edge of the Sundarbans, whose tomb inscription names him “Ulugh Khan-i ‘Azam Khan Jahan,” indicating a Turkic origin and high rank in the Bengal sultanate. Nineteenth-century traditions credit him with reclaiming forested waste for rice cultivation, converting local populations, and constructing roads and mosques after receiving a jagir from the ruler of Gaur. His large-scale works imply control over revenue and labour as a major zamindar, before he ultimately withdrew from worldly authority to live as a faqir.

Sixteenth-century literary reflections and agrarian epic

Mukundaram’s poem can thus be read as a grand epic dramatising the process of civilisation-building in the Bengal delta, and specifically the push of agrarian civilisation into formerly forested lands. It is true that the model of royal authority that informed Mukundaram’s work is unambiguously Hindu. The king, Kalaketu, was both a devotee of the forest goddess Chandi and a Hindu raja in the medieval (that is, post-eighth-century) sense, while the peasant cultivators in the poem showed their allegiance to the king by accepting betel nut from his mouth—an act drawing directly on the common Hindu ritual expressing devotion to a deity, the pūjā ceremony.

Yet it was Muslims who were the principal pioneers responsible for clearing the forest, making it possible for both the city and its rice fields to flourish. “The Great Hero [Kalaketu] is clearing the forest,” wrote the poet:

Hearing the news, outsiders came from various lands.

The Hero then bought and distributed among them

Heavy knives [kāṭh-dā], axes [kuṭhār], battle-axes [ṭāngī], and pikes [bān].

From the north came the Das (people),

One hundred of them advanced.

They were struck with wonder on seeing the Hero,

Who distributed betel nut to each of them.

From the south came the harvesters,

Five hundred of them under one organiser.

From the west came Zafar Mian,

Together with twenty-two thousand men.

Sulaimani beads in their hands,

They chanted the names of their pīr and the Prophet [pegambar].

Having cleared the forest,

They established markets.

Hundreds and hundreds of foreigners

Ate and entered the forest.

Hearing the sound of the axe,

Tigers became apprehensive and ran away, roaring.

Late sixteenth–early seventeenth century European accounts of Bengal’s agrarian abundance

In 1567, Cesare Federici judged Sandwip to be “the fertilest land in all the world,” and recorded that one could obtain there “a sack of fine rice for a thing of nothing.” Twenty years later, when ‘Isa Khan still held sway over Sonargaon, Ralph Fitch wrote: “Great store of Cotton doth goeth from hence, and much Rice, wherewith they serve all India, Ceilon, Pegu, Malacca, Sumatra, and many other places.”

The most impressive evidence in this regard comes from François Pyrard. After spending the spring of 1607 in Chittagong, still under independent rulers beyond the Mughals’ grasp, the Frenchman wrote: “There is such a quantity of rice that, besides supplying the whole country, it is exported to all parts of India, as well to Goa and Malabar as to Sumatra, the Moluccas, and all the islands of Sunda, to all of which lands Bengal is a very nursing mother, who supplies them with their entire subsistence and food. Thus, one sees arrive there [i.e., Chittagong] every day an infinite number of vessels from all parts of India for these provisions.” François Pyrard, The Voyage of François Pyrard of Laval to the East Indies, the Maldives, the Moluccas and Brazil, ed. and trans. Albert Gray.

Seventeenth century: Mughal state and the agrarian order

From the reign of Akbar onward, the Mughals sought to integrate Indians into their political system at two levels. At the elite level, they endeavoured to absorb both Muslim and non-Muslim chieftains into imperial service, thereby transforming potential state enemies into loyal servants. They also sought to expand the empire’s agrarian base, and hence its wealth, by transforming forest lands into arable fields and the semi-nomadic forest-dwelling peoples inhabiting those lands into settled farmers.

“From the time of Shah Jahan [1627–58],” records an eighteenth-century revenue document, “it was customary that wood-cutters and plough-men used to accompany his troops, so that forests might be cleared and land cultivated.… Ploughs used to be donated by the government. Short-term pattas were given, with fixed government demand at the rate of one anna per bigha during the first year. Chaudhuris were appointed to keep the ri‘aya happy with their considerate behaviour and to populate the country. There was a general order that whosoever cleared a forest and brought land under cultivation, such land would be his zamindari.”

An undated order by Aurangzeb (1658–1707) reveals a similar concern with increasing arable acreage, adding that should any peasant flee the land, the local revenue officers should ascertain the cause and work very hard to induce him to return to his former place. Such an appeal hardly suggests a state bargaining from a position of strength. In fact, it points to the chronic surplus of land over labour that obtained in premodern India generally, and in Bengal until as late as the mid-nineteenth century.

In the settled western and north-western parts of Bengal, Mughal officials collected land tax from the Hindu peasantry at full rates through Kayasthas and other zamīndārs. In the less cultivated eastern and southern regions, the government encouraged the establishment of new agrarian colonies, often led by individuals with local religious influence, as they were seen as connected to stable, reliable institutions.

Assam followed a different political trajectory but shared a similar flexibility. As J. N. Sarkar documents in History of Assam, Ahom rulers measured strength through manpower and service obligations, not cadastral precision. When populations shifted—through warfare, environmental change, or economic opportunity—the state adapted by absorbing newcomers rather than excluding them. What mattered was incorporation into the labour and tribute system, not ancestry or place of origin.

Crucially, none of these systems required a sharp distinction between “indigenous” and “migrant” as fixed identities. The idea that a person’s legitimacy depended on where their ancestors had lived was largely absent. Belonging was produced over time through cultivation, contribution, and coexistence.

In India Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality, Sanjib Baruah emphasises that the Bengal–Assam region functioned as a fluid world long before colonial intervention, where rivers, forests, and seasonal rhythms guided movement more than political boundaries. Trade, labour, and cultivation flowed across landscapes naturally, and communities absorbed newcomers without rigid distinctions. Under Ahom rule, land was tied to service and allegiance through the paik system rather than fixed ownership, and belonging was produced over time through participation, cultivation, and social incorporation rather than ancestry. Seasonal labour, agrarian expansion, and cross-regional movement were therefore normal and stabilising, not disruptive, highlighting that colonial anxieties about migration emerged only when the state imposed classification, enumeration, and rigid legal categories on previously flexible social and ecological systems.

This historical reality complicates later colonial claims that migration into Assam represented an unprecedented rupture. As Amalendu Guha notes in Planter Raj to Swaraj, the anxiety surrounding Bengali settlement in Assam emerged not because movement was new, but because colonial capitalism altered the scale, speed, and visibility of demographic change—while simultaneously narrowing the criteria for belonging.

In contrast to the agrarian expansion and cultural assimilation observed in premodern Bengal, Assam under the Planter Raj illustrates the limits of colonial modernisation. The introduction of plantation agriculture and a market-oriented economy could not effect a radical transformation of local society. Urbanisation remained negligible, and the emerging Assamese middle class was small, weak, and unconsolidated. Most inputs for the modern sector—capital, enterprise, and labour—came from outside the province, leaving local peasant economies only tenuously connected. In this plural, multi-sectoral economy, tribalism and feudal remnants persisted alongside promising capitalist relations, stifling the early development of political consciousness. Yet the peasantry, burdened by land revenue and new taxes, maintained a quiet but persistent resistance to colonial authority. Over time, the middle class began to recognise imperialism as the root of social and economic grievances, gradually engaging with electoral politics and aligning with broader freedom movements—though this process was slow and mediated by the constraints of colonial structures.

Why this history matters

This history matters because it reminds us that mobility between Bengal and Assam is not an aberration or a modern crisis, but a long-standing social reality shaped by rivers, trade, cultivation, and shared livelihoods rather than by borders. Before colonial rule, people moved to farm land, follow watercourses, trade goods, and build communities in ways that made sense locally, without rigid ideas of territory or fixed identities. Recovering these pasts challenges present-day narratives that treat movement as intrusion and populations as outsiders. It shows that today’s anxieties are rooted not in ancient hostilities, but in relatively recent policies that imposed lines on a landscape that had long functioned through connection, circulation, and coexistence.

Bibliography

Baruah, Sanjib. India Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999.

Eaton, Richard M. The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press, 1993.

Federici, Cesare. The Travels of Cesare Federici. Translated and edited in early modern travel collections on Asia; originally published in 1567.

Fitch, Ralph. The Voyage of Master Ralph Fitch, Merchant of London, 1583–1591, in Samuel Purchas (ed.), Purchas His Pilgrimes.

Gray, Albert (ed. and trans.). The Voyage of François Pyrard of Laval to the East Indies, the Maldives, the Moluccas and Brazil. Hakluyt Society, 1887.

Guha, Amalendu. Planter Raj to Swaraj: Freedom Struggle and Electoral Politics in Assam, 1826–1947. Indian Council of Historical Research / People’s Publishing House, 1977.

Guha, Ranajit. A Rule of Property for Bengal: An Essay on the Idea of Permanent Settlement. Duke University Press, 1996.

Hölzle, Éva Rozália. “The Formation of the Sylhet–Meghalaya–Assam Border.” Asian Journal of Social Science. Brill.

Ludden, David. An Agrarian History of South Asia. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Mukundaram Chakrabarti. Caṇḍī-Maṅgala. Sixteenth-century Bengali literary text.

Sarkar, J. N. A History of Assam. B. R. Publishing Corporation.

Shaila Shobnam is a barrister-in-training at BPP University, Britain, and an LL.B. (Hons) graduate of the University of London.

Send your articles to Slow Reads for slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.