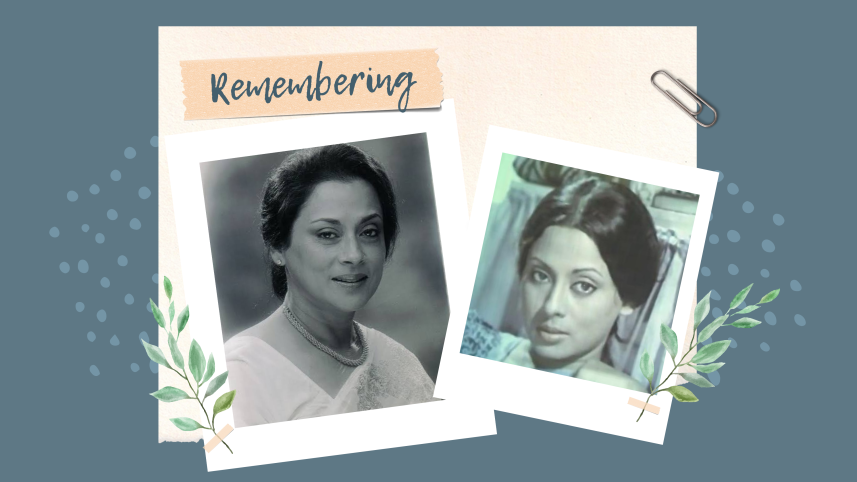

Remembering Jayasree Kabir: The actress who chose absence

Jayasree Kabir died at the age of seventy-three, and true to the life she had chosen, her passing announced itself first as an absence. By the time news reached many of us, nearly two days had already passed. She died in a nursing home in Romford, on the outskirts of London—far from film premieres and public tributes, far from the cinemas where her presence once held audiences in quiet attention.

The delay was not accidental. For decades, Jayasree Kabir had lived outside the public gaze. Her withdrawal was neither embittered nor dramatic; it was deliberate, measured, and dignified. She chose privacy long before it became fashionable to speak of it as self-care.

To those who grew up watching Bengali cinema during its most creatively vibrant years, Jayasree Kabir was more than an actress. She embodied a particular kind of screen intelligence—restrained, thoughtful, and emotionally precise. Her beauty was never overtly performative. It emerged instead through stillness, through a gaze that suggested thought rather than display. Even today, when clips from her films resurface online, it is often her face—quiet, attentive, composed—that holds the viewer longer than the narrative itself.

I first encountered her nearly fifteen years ago at the Genesis Cinema in East London, during the Rainbow International Film Festival. The cinema—modest, slightly worn, and deeply loved—has long been a gathering place for independent and world cinema. Jayasree Kabir sat among the audience, leaning forward slightly, watching with a concentration that suggested she remained, in some essential way, a student of film. She wore no visible markers of celebrity. Yet her presence carried an unmistakable gravity.

Over the years, we crossed paths occasionally at film events. She was invariably understated and quietly attentive. Because of my regular presence on television, she was familiar with my work, and our brief exchanges were marked by warmth and generosity. On one occasion, she approached me herself to speak kindly about my work. When I responded by telling her what her performances had meant to me as a young viewer, she listened with a faint, almost embarrassed smile. Praise, it seemed, unsettled her more than silence.

As a member of the organising committee of the Rainbow International Film Festival, I often found myself in informal, post-festival conversations with Derek Malcolm, the renowned British film critic who spent many years at The Guardian. In those animated exchanges, Jayasree Kabir’s presence was quietly commanding. She never raised her voice or sought attention, yet her interventions brought immediate clarity. Drawing on lived experience rather than theory, she anchored abstract debates in the realities of filmmaking and performance. In those moments, she did not seem like a former actress reflecting on the past, but a living archive of cinema—attentive, incisive, and fully engaged with the art form she had never truly left.

A more unforgettable encounter took place at the home of Mostafa Kamal, founder of the Rainbow Film Society and director of the Rainbow International Film Festival. It was one of those evenings where time seems suspended, where cinema is not a profession but a shared memory. Jayasree Kabir sat in a low chair, legs crossed, speaking in her calm, measured tone. She recounted her early life in Kolkata, spoke about winning Miss Calcutta in 1968, and how that moment—glamorous as it was—had not been an end in itself, but a doorway to something larger.

“Winning Miss Calcutta opened doors,” she said with a faint smile, “but it was only a beginning. Cinema demanded something different—something deeper.” She paused, tapping her fingers lightly on her knee. “I was fortunate to meet remarkable people early on.”

Her first real step into cinema came when Satyajit Ray cast her in The Adversary (Pratidwandi, 1969). She spoke of Ray with deep admiration, describing the opportunity as both significant and formative. “Working with him was extraordinary,” she said, leaning forward slightly. “He expected precision, but he also made you feel that the camera would capture exactly what you offered—nothing more, nothing less.” Every scene, she felt, became a lesson that stayed with her throughout her career.

It was also at Satyajit Ray’s home that she first met Alamgir Kabir. At the time, competing film projects were underway. Recalling that meeting, Jayasree Kabir reflected that there was nothing particularly striking at first sight. But as Alamgir Kabir began speaking with Satyajit Ray, she gradually became aware of the depth of his knowledge. His understanding of cinema surprised her, and that initial conversation altered her perception. If not love at first sight, it was certainly admiration at first acquaintance. His personality, she said, left a lasting impression on her.

During her years in Kolkata, Jayasree Kabir appeared in more than forty films, working across genres without being confined to a single screen persona. She shared the screen with some of Bengali cinema’s most iconic figures, including Uttam Kumar, whom she remembered for his generosity towards younger actors. Even in commercially uneven projects, her performances retained discipline and clarity.

A major turning point came when she moved to Bangladesh, where Alamgir Kabir was a central figure in a national cinema emerging after the country’s war of independence. Jayasree Kabir became part of that creative reckoning, appearing in a small number of films that left a disproportionate cultural impact. Her screen presence—particularly in a now-classic song sequence from Shimana Periye—remains deeply etched in public memory.

Her marriage, however, eventually ended in separation. Leaving Bangladesh carried a quiet sense of loss—one she rarely articulated directly. After the divorce, she returned to Kolkata and subsequently settled in London with her son, Lenin Saurav Kabir. Alamgir Kabir’s death in 1989 closed a chapter that had shaped her both personally and artistically.

London offered her something she valued deeply: anonymity. She lived with restraint, appearing occasionally at film festivals, recording voice work for the BBC and Channel 4, and representing Satyajit Ray at international events. She followed developments in South Asian cinema closely, but resisted re-entering public life.

That resistance may explain why news of her death travelled slowly. She had made herself intentionally difficult to reach. Once, she agreed to an interview with me but cancelled shortly beforehand, distressed by abusive online comments beneath an old film clip. The incident revealed a vulnerability beneath her composure—a reminder of how deeply even private individuals can be wounded by public cruelty.

In her final months, according to Mostafa Kamal, Jayasree Kabir was hospitalised at the Royal London Hospital with lung disease and multiple complications. “Her condition was gradually deteriorating,” he said, “but she remained fully conscious and remarkably strong. Even then, her mental resilience was striking.”

That resilience defined her life. Like other great screen icons who chose disappearance over self-exposure, Jayasree Kabir understood that absence can be an assertion of dignity. She refused to let her legacy be shaped by noise or nostalgia.

Her life feels, in retrospect, like a long fade-out—intentional, unhurried, and controlled. She left behind no memoirs, no public manifestos, no digital trail. What remains are films, fleeting images, and the memory of a woman who understood the power of restraint.

Jayasree Kabir’s death closes a chapter in world cinema that valued seriousness, integrity, and inner strength. She will continue to return—not loudly, not often—but unexpectedly, through an old film clip, a remembered performance, a gaze that still holds attention.

And perhaps that is exactly how she intended to be remembered.

Bulbul Hasan is a British-Bangladeshi journalist and writer with over two decades of experience across television, print, and digital media. He is currently the UK Correspondent-at-Large for The Daily Star.

Send your articles to Slow Reads for slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.