Without the rule of law, nothing else will work

The mass uprising that toppled Bangladesh’s authoritarian regime ushered in a profound moment of new hope. However, the path to a restored democracy has proven far more arduous than anticipated. The interim government, which took charge on August 5, 2024, quickly eroded public trust through its frustrating failure to meet core objectives. Its performance was defined by an inability to ensure economic stability or maintain law and order—basic expectations for any caretaker administration. Notably, its strategy of appointing advisers with strong economic backgrounds yielded no positive results, highlighting a deeper crisis of governance rather than one of mere technical expertise.

Amid these failures, a performative drive to claim achievements took hold. The Adviser to the Law Ministry, for instance, maintained a high-pitched rhetoric of progress. Yet beneath this impressive edifice, a foundational tremor persists: the continued weakening of the rule of law and judicial independence. This erosion strikes at the very bedrock upon which sustainable prosperity and genuine democracy are built. Consequently, for the upcoming government, regardless of its political composition, addressing this crisis cannot be treated as a peripheral legal issue. It must be the central, unifying priority. This is not merely a moral imperative but an existential necessity for the nation’s future.

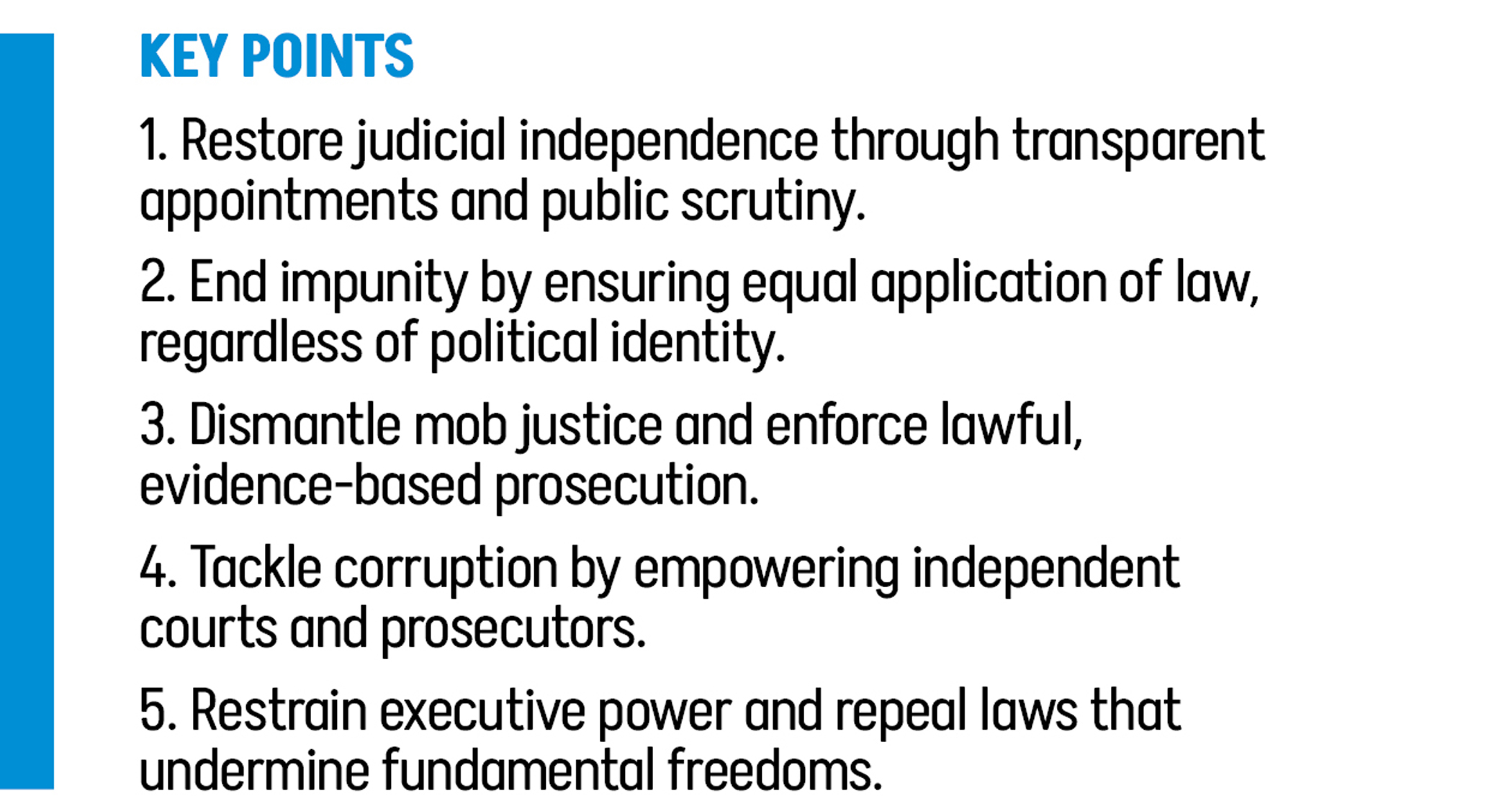

The narrative of Bangladesh’s recent decades is often, and rightly, framed as one of remarkable economic growth and poverty reduction. However, this narrative is increasingly shadowed by a parallel story of institutional erosion. The symptoms are visible to all: the blurring of lines between the executive and the judiciary; the use of legal instruments for political convenience; the slow pace of justice that denudes it of its meaning; and a culture of impunity that, for the powerful, renders the law a suggestion rather than a mandate. The most acute manifestation of this crisis is the compromised perception of judicial independence. The judiciary is not merely a dispute-resolution mechanism; it is the guardian of the Constitution, the protector of fundamental rights, and the ultimate arbiter that ensures all power, including state power, is exercised within legal bounds. When public confidence in this institution wavers, the social contract frays. Concerns over appointments, transfers, and the perceived influence of the executive branch have produced a chilling effect. The justice system, overburdened and frequently undermined, struggles to serve as the people’s shield.

The mass uprising promised a return to order under expert, impartial legal authority. Instead, it produced a dangerous transmutation: the implementation of law was replaced by a sanctioned mob culture. Organised acts of retribution and crime were often euphemistically labelled as “mob attacks”, a terminology that served to obscure their orchestrated nature and evade formal accountability.

This created a perilous dual reality: the façade of legal process alongside the brute-force enforcement of political will. Most critically, this erosion fatally compromised the institution designed to be the final bulwark—the judiciary. The principle is sacrosanct: once a case is before a court, only the law and the facts should matter. Yet in countless instances following the regime’s fall, courts across the hierarchy failed this basic test of objectivity. The political identity of the accused, particularly their association with the fallen regime, became an overwhelming, if unspoken, factor in judicial decision-making.

This represents more than partiality; it is the judicialisation of the political victor’s justice. When courts cannot separate individual culpability from collective political identity, they cease to be arbiters of law and become instruments of political consolidation. The promise of the uprising—a new foundation built on justice and law—is thus hollowed out, replaced by a system in which the forms of legality mask a continuation of polarised conflict, merely with reversed beneficiaries. The failure to establish genuine, neutral legal authority is the single greatest threat to the durable democracy that was sought.

Furthermore, the rule of law deficit directly fuels the pervasive corruption that every political party vows to fight. Corruption is not merely a moral failing; it is a structural outcome of a system in which legal accountability is selective. When the law can be bent, bypassed, or weaponised, rent-seeking becomes a rational strategy. The upcoming government must understand that anti-corruption drives, without an overarching, immutable framework of law applied equally to the powerful and the weak, are destined to be seen as political theatre. A truly independent judiciary and a robust, impartial prosecutorial body are the only engines for sustainable anti-corruption, not temporary commissions or rhetorical campaigns.

The erosion of the rule of law also stifles the very creativity and civic vitality Bangladesh needs for its next chapter. A society in which dissent is criminalised through opaque legal processes, in which civil society operates under a spectre of surveillance and restriction, and in which the media fears overreach, is a society that loses its capacity for self-correction and innovation. The vibrant intellectual and entrepreneurial spirit of Bangladesh cannot reach its full potential in an environment of legal uncertainty and fear. The right to speak, to associate, and to hold power accountable are not Western imports; they are enshrined in Bangladesh’s own Constitution and are prerequisites for a resilient, adaptive, and just society.

Therefore, for the incoming government, prioritising the rule of law and judicial independence is not a concession but a strategic masterstroke. It is the key that unlocks success in all other priority areas. How can this be translated from a lofty principle into a concrete governance agenda?

By invoking contempt of court, the judiciary has long shielded itself from criticism, often to mask its own failings. This resistance to scrutiny has impeded the development of a truly independent judicial system. Courts must instead learn to endure critique as a necessary part of progress. It is fundamentally unjust to deny ordinary citizens—the very people subjected to open trials—their right to question the institution. An entity charged with delivering justice cannot itself act unjustly. Ultimately, the judiciary will only course-correct when the public is empowered to actively question its functioning. Therefore, a key goal for the next elected government must be to foster this public empowerment and enable deeper citizen engagement with judicial processes.

The recruitment process for Supreme Court judges remains opaque, despite new legislation permitting prospective candidates to apply directly and establishing a committee to oversee the recruitment process. The specific criteria and selection procedures continue to lack public transparency. Moreover, key provisions of the ordinance appear to contradict established constitutional principles, notably by diminishing the traditional primacy of the Chief Justice in judicial appointments. The elected government must therefore endeavour to scrutinise the ordinances passed during the interim administration and refrain from mechanically endorsing them without due examination.

The next government must embark on a war against the case backlog and judicial delay. This requires massive investment in court infrastructure, digitalisation of case management, an increase in the number of judges and court staff, the provision of adequate training, and the streamlining of procedures. Speedy justice is a fundamental right; delay is a denial of justice. A special focus must be placed on lower courts, where most citizens encounter the legal system, to ensure they are adequately resourced and insulated from local power dynamics.

The government must demonstrate an unwavering commitment to ending impunity. This means allowing and empowering law enforcement and anti-corruption agencies to operate without political interference, even when investigations touch powerful interests within, or aligned with, the ruling structure. High-profile, credible prosecutions and convictions in corruption and abuse-of-power cases would do more to restore public faith than a thousand speeches.

It must undertake a comprehensive review and repeal of laws that curtail fundamental freedoms and are prone to abuse. Laws pertaining to digital security, sedition, and civil society regulation should be aligned with international human rights standards and the spirit of the Constitution. The law must protect citizens, not the state from its citizens.

The government must practise restraint. The executive must lead by example, voluntarily submitting itself to the jurisdiction and scrutiny of an independent judiciary. It must refrain from using legal tools to settle political scores or silence critics. This political will from the very top is the single most important catalyst for change.

Critics will argue that in a developing nation facing immense pressures, a strong, unfettered executive is more effective in delivering results. This is a dangerous fallacy. Authoritarian efficiency is illusory and ephemeral. It builds towers but weakens foundations, leading to catastrophic fragility in the long term. True, sustainable strength is derived from institutions that command universal respect, from a legal system that citizens trust, and from a social order in which every individual, from the street vendor to the cabinet minister, is equally accountable.

The task is Herculean, and the path will be resisted by vested interests that thrive in the shadowy gaps of a weak rule-of-law framework. It will require a statesmanship that transcends the political cycle, viewing national interest through a generational lens. The upcoming government faces a historic choice: to continue papering over these deepening cracks with the plaster of short-term development metrics, or to undertake the courageous, patient work of repairing the foundation.

Bangladesh’s journey from liberation to development is an epic of resilience. Yet the symphony of its potential remains unfinished. The notes of economic growth, infrastructural marvels, and cultural richness are all present, but they lack harmony and coherence without the conductor of a just rule of law. It is time for the government to pick up that baton, not to silence the orchestra, but to allow every instrument—every citizen, every institution—to play its part in perfect, fearless harmony. The next chapter of Bangladesh’s story must be written not on concrete and steel, but on the immutable parchment of justice. For in the end, a nation’s greatness is measured not by the height of its skyscrapers, but by the depth of its commitment to law.

Jyotirmoy Barua Advocate, Bangladesh Supreme Court

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.