Towards a 'just transition' in the labour market: Rights, gender and environment

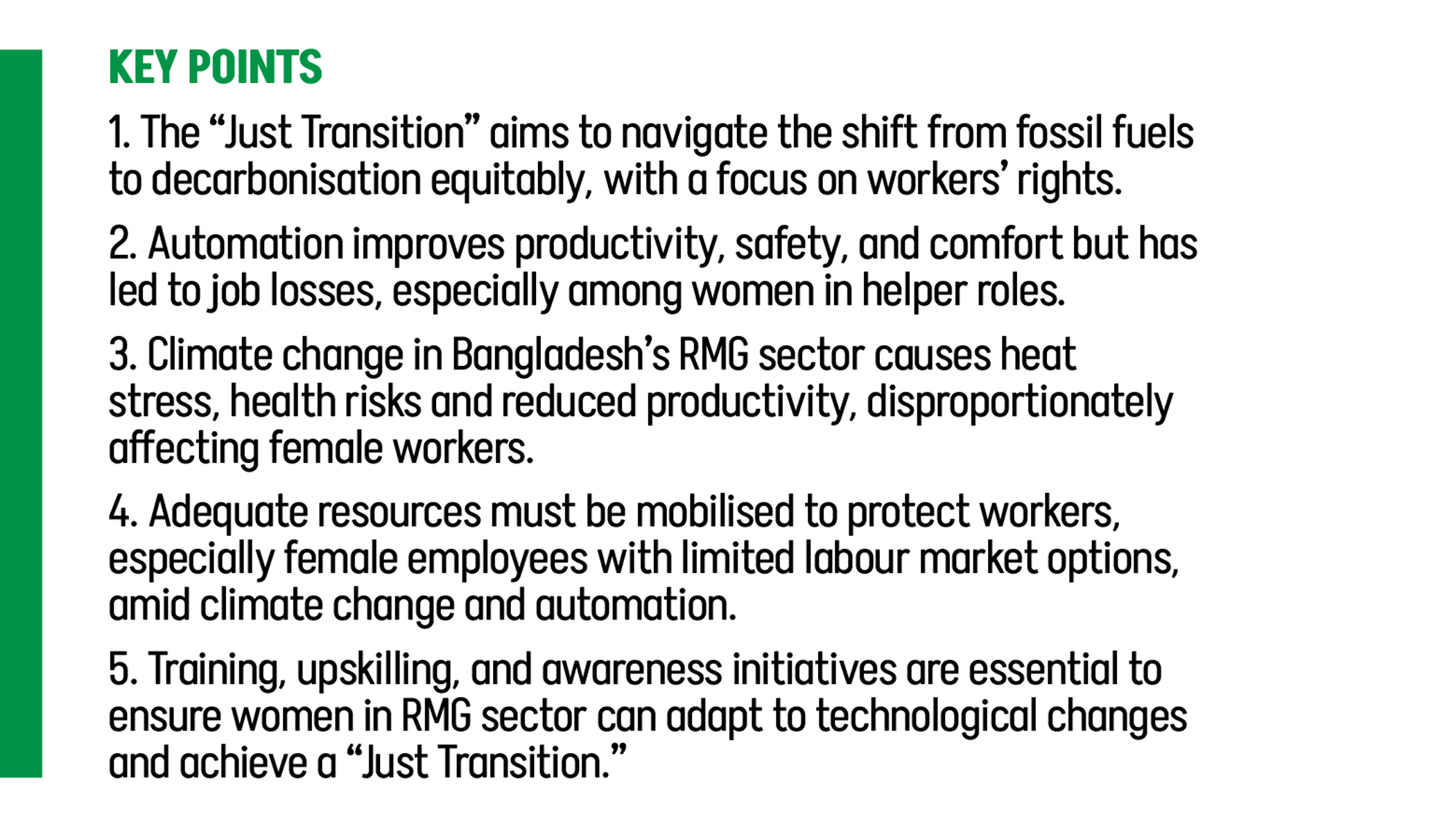

The labour market worldwide is going through major transformations driven by climate change. It is reshaped by the transition towards an environmentally friendly workplace. Poorly managed transitions could lead to hardships in industries, particularly those relying on fossil fuels. The idea of a “just transition” is therefore gaining prominence as a means to navigate the shift from fossil fuels to decarbonisation equitably, with a specific focus on workers’ rights. This concept of a “Just Transition” originated in the 1970s when labour unions advocated for support for workers affected by environmental regulations.

Over the years, the ‘Just Transition’ concept has extended internationally as well, recognising the need to address the uneven distribution of the burdens and costs associated with the impact of climate change. The ‘Just Transition’ framework is also applicable to another crucial transformation driven by digital technology, such as automation. Whether labour rights are protected by the shift from basic to advanced technology is also a major concern. Both changes – climate and technology - carry opportunities and challenges for workers in the ready-made garment (RMG) industry, the second largest exporter of garments in the world. Under these circumstances, the objective of this writing is to understand ‘Just Transition’ in the RMG industry by understanding the impact of climate change and automation on female garment workers who comprise the major workforce of this industry.

The RMG sector has emerged as a cornerstone of the Bangladeshi economy, generating around 4.2 million jobs and advancing women’s empowerment and financial independence. With its substantial contribution of over 10% to GDP and its accounting for 84% of foreign earnings, it stands as a vital force for progress. Despite benefiting from this sector, it grapples with climate change vulnerabilities. The garment and textile sector in Bangladesh remains heavily resource-constrained and pollution-intensive. In fact, the RMG sector is the most significant contributor to CO2 emissions (at 15.4%) in Bangladesh (Green Climate Fund, 2020), which poses a huge risk to the health of its workers. However, health effects from toxic fumes or chemicals have thus far been addressed only sparingly in the global discourse. Current concerns regarding the impact of climate change on workers in the RMG sector mostly focus on heat stress and productivity. Not only does heat stress diminish labour performance, but it also curtails labour supply and productivity, with the potential of increased absenteeism during hotter periods (Letsch et al., 2023). Such productivity loss affects economic output and wages, impacting local economies and communities in the process (Kahn et al., 2021). In Dhaka’s garment factories, temperatures can reach 38°C during peak production hours, posing significant risks to workers, as high indoor temperatures can cause suffocation.

Furthermore, from one of my research projects on stakeholder perceptions of environmental sustainability, conducted in collaboration with the Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI), it was noted that women are cited as bearing the brunt of the consequences of climate change. This is because they are more likely to be absent from work due to having disproportionate care duties within their domestic sphere. Losses in income due to reduced productivity can be particularly challenging for women, as they have limited access to resources and ownership and already earn lower wages. Additionally, as gender-based violence and harassment are already pervasive throughout the RMG sector and lower productivity is a driver of violence and harassment in the workplace, studies indicate that decreasing levels of productivity due to climate change may potentially result in heightened levels of harassment against female workers (ILO, 2019). Extreme weather conditions leading to heat stress, absenteeism etc. can thus exacerbate these cases of violence. From the theoretical framework of ecofeminism, there is a clear gap in the acknowledgement of women’s health and their particular health vulnerabilities due to the environment, which furthers their economic and social inequities, such as job mobility and income. Many women are even shown to quit their jobs after a specific period due to a lack of proper health amenities, which are now even more necessary, due to the increasing weather turbulence and climate change. The difference in attitude between women-centric and male-dominated managerial bodies is extremely telling. While further investigation is required to properly assess gender differences within perceptions, where organisations with female management need to be compared and contrasted with male-dominated organisations, the significance of female voices within this battle for a green transition has been illuminated through the findings of this study.

The “Just Transition” in the changing nature of work can also be analysed by evaluating the effects of automation on women workers, as evidenced by my research in collaboration with the Bangladesh Labour Federation (BLF). Automation in Bangladesh’s RMG industry has drastically transformed the operational and social landscape, yielding numerous benefits for both factories and workers. While the transition to automated processes has not been without challenges, its positive outcomes underscore the potential of technology to drive productivity, quality, and improved working conditions. The advancement of technology in factories has brought notable improvements in workplace safety and comfort, particularly by reducing the physical strain of repetitive and labour-intensive tasks. Another benefit of modern machines is their ability to count production automatically. Previously, women workers spent four to five minutes manually counting the number of pieces they had completed. Still, advanced sewing machines now perform this task automatically, displaying the count on a screen. This feature saves time and has increased production rates. Automation has also enabled women workers to complete tasks more quickly, giving them more time to relax at work and spend time with their families. Tasks that previously required an additional hour on older machines now take an hour less on advanced machines. According to a worker, “With the older machines, cutting thread by hand wasted time, and we couldn’t take breaks or even drink water without reducing our output. Now, with automated machines, we work more relaxedly.”

However, women workers have experienced adverse effects from technological advances. My study indicates that fewer workers were required in the factory following automation. In the survey, the workers were asked which group was replaced more: males or females. 62% of the workers said more women were replaced. As evidenced by this study, the number of helpers (the majority were women) has decreased following the introduction of new machines. In this context, one of the workers stated, “Before the automatic machines came, a large number of women worked as helpers. Now that automated machines have been introduced, we no longer require many helpers. As a result, a lot of women lost their jobs.”

In Bangladesh’s RMG industry, gender inequality is starkly evident in senior production roles, such as CAD operations. While most garment workers are women, they remain concentrated in lower-level sewing roles, with men dominating digital jobs in CAD departments due to technical education or internal promotions. This disparity leaves women behind in a rapidly evolving industry. Stakeholders must prioritise providing women with access to CAD training, as their understanding of clothing construction offers a solid foundation for upskilling.

Physical demands also contribute to inequality. Women often avoid training for processes such as denim production, which require physical strength, and instead focus on sewing tasks. Machines with complex mechanisms, like Jacquard and Kansai, are predominantly operated by men, leading to higher salaries and additional benefits for male workers. Women, by contrast, earn less and receive fewer privileges, further widening the gender gap.

Social structures and cultural norms, including religious restrictions, also discourage women from pursuing advanced training. However, women who do attend these initiatives often adapt equally well as their male counterparts. Household responsibilities frequently prevent women from attending training sessions outside of their shifts. Additionally, lower educational attainment among women in Bangladesh makes adaptation to automation more difficult. As noted by a factory manager, some female workers still struggle with basic literacy tasks, such as signing their names, highlighting the need for better support and targeted training to help women adapt to the changing workplace.

The objective of this writing was to explore the “Just Transition” in the RMG industry in Bangladesh, given changes in the nature of work and their impact on women workers. From the context of climate change and automation, it was revealed that adequate resources need to be mobilised to protect workers— with a particular focus on female employees who have limited options available in the labour market. In this process, concrete research should be conducted to showcase more evidence on the relationship between climate change, automation, and their effects on women workers.

Social safety nets for this group of workers remain inadequate; therefore, the green transformation could make their lives more vulnerable. The government has already taken a significant contribution to the garment industry’s development. However, the government can address the challenges of the changing nature of work by training workers to adapt with these changes. Awareness of career advancement is essential by educating women workers about the relationship between adaptation to technology and income. If the government, labour organisations, NGOs, and other development partners provide appropriate training and workshops, it will immensely benefit the apparel industry and ensure ‘Just Transition.’

Dr. Shahidur Rahman is a Professor of Sociology in the Department of Economics and Social Sciences at BRAC University. His recent publication was an edited book titled “Social Transformation in Bangladesh: Pathways, Challenges, and the Way Forward,” published by Routledge in 2025.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details