Rural lives on the move: Why Bangladesh must rethink rural–urban migration

Since independence, rural–urban migration has shaped the socioeconomic landscape of Bangladesh. Yet the ways in which it unfolds create tensions around development, opportunities, and survival. People move from villages not only for income, status, and education, but also in the hope of finding relief from uncertainty that shapes their decisions regarding migration. As the country prepares for a long-awaited elected government in early 2026, the longstanding demands arising from repeated waves of migration require comprehensive attention. Given global scenarios and prevailing migration trends, it should be considered a crucial phenomenon that affects economic growth, social solidarity, and the everyday struggles of millions in both rural and urban areas.

Over the last few decades, lifeways in most rural areas have shifted in such a manner that, sooner or later, they motivate rural–urban movement. Currently, agriculture provides less stable income, land has become increasingly fragmented, and weather patterns have grown more unpredictable in most rural regions. Although rural people choose migration, multiple pressures shape this preference. Researchers have observed how people talk about migration using the rhetoric of necessity rather than adventure. It is often described as something one must do to protect one’s family. This moral framing shows how migration aligns more with family expectations than with individual aspirations.

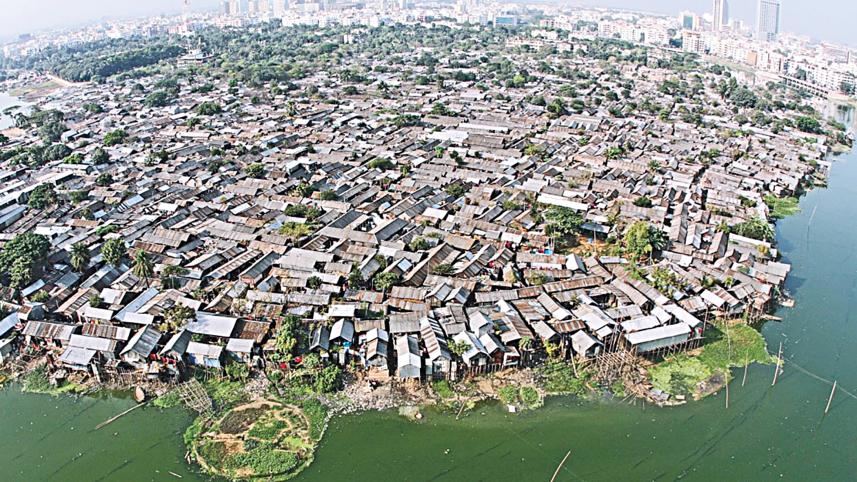

Dhaka, Chattogram, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Cumilla attract new migrants every month, which implies a lack of opportunities in migrants’ rural areas. These cities are no longer capable of supporting their already overpopulated residents, let alone new arrivals. Migrants usually work in garment industries, construction sites, and the transport sector, while some find employment in formal sectors. They contribute significantly to strengthening the national economy, yet their living environments often lack fundamental living standards.

One of the major reasons for this situation is rapid and unplanned urbanisation without adequate consideration of migrants’ living standards or the carrying capacity of cities. With about 36.6 million people, Dhaka has become the second-largest city in the world in terms of population, and the capital is incapable of adequately supporting its residents and the growing migrant population in areas such as employment, housing, security, and disaster management, creating an overall state of disorder. The second-largest city, Chattogram, also shares a similar fate for its residents.

Social researchers, including anthropologists, offer insights into how migration has shaped and introduced new patterns in family structure and mental life. When a man or a woman leaves a village for a city, the decision does not merely involve economic issues such as employment and income; it also encompasses kinship obligations, social networks, and responsibilities. Remittances sent from cities become lifelines for families left behind. Food for parents, school fees, and medical expenses often depend on these remittances. Over time, migrants’ presence becomes social rather than merely physical, spreading through mobile phones and digital platforms. These bonds help rural families remain afloat, yet they also intensify emotional distance that receives little policy recognition.

Rural people often narrate migration as a form of loss. Elders speak of empty courtyards, abandoned homesteads, and fading heritage. At the same time, they acknowledge that migration sustains the family economy while they face land scarcity and worsening conditions caused by climate disruption. These dual perceptions—loss and survival—reveal why migration cannot be viewed solely through economic lenses. It touches upon identity, memory, and social continuity. If policy aims to engage with lived experiences rather than abstract data alone, the upcoming government must recognise this nuanced dimension.

On the urban side, migration from rural areas reshapes neighbourhoods and city culture. Informal settlements become hubs of new languages, foods, norms, customs, and forms of rural solidarity. Migrants recreate village-based networks within cities, often organised around their districts of origin. These networks provide social security, employment information, and psychological support. Urban planners rarely acknowledge these social landscapes, yet they are essential to migrants’ survival. If the next elected government seeks to manage cities effectively, it must recognise these networks not as obstacles, but as strengths.

Housing has remained one of the most crucial problems connected with migration. Millions live in crowded settlements without basic amenities and secure tenure. Fires, evictions, poor sanitation, and flooding are regular threats in most settlements. Residents are aware of this uncertainty; they consider themselves as ‘city guests’. However, they remain patient, even though their situation never becomes stable or permanent. If the upcoming political leadership intends to reduce urban vulnerabilities, then strengthening affordable housing, enhancing legal safeguards, and promoting community-led leadership upgradation should become priorities. Policies should shift from eviction-based solutions to long-term stability; migrants should not be considered a burden but should instead have their contributions recognised.

Transport is another sector where migration pressure is evident in major cities. Every morning, thousands of workers travel from densely populated and remote settlements to industrial areas.

On their way to their workplaces, they are often stuck in traffic jams for long periods, or they have to walk through unsafe roads. These situations affect their productivity, health, and overall well-being. Urban transport reform often focuses on large-scale infrastructure; however, migrant workers need affordable, reliable, and safe options. To achieve this, coordinated planning is essential among ministries, city corporations, and transport agencies. Without addressing mobility challenges, urban centres will continue to absorb migrants without enabling them to thrive.

Employment is one of the most influential drivers of rural–urban migration. However, the job market is structurally unequal for most migrants, who enter informal work without legal security or long-term pathways. Garment workers face unpredictable shifts, construction workers endure insecure conditions, and domestic workers remain invisible in policy discussions. By implementing extended labour inspections and enforcing labour security policies, the upcoming government may encourage industries to establish more humane working environments. Migration should not mean accepting exploitation as the cost of survival.

The unpredictable effects of climate change will necessitate migration in the coming years. Salinity intrusion, cyclones, riverbank erosion, and irregular rainfall have already pushed coastal and riverine families towards cities. These climate migrants often move suddenly, without formal networks or stable income sources. Their needs differ from those of migrants driven primarily by economic reasons. The future government must develop forward-looking plans and invest in strengthening climate-resilient agriculture, improving rural employment diversification, and constructing safe housing settlements in vulnerable areas. Delaying these steps will only intensify chaotic urban growth.

Education plays a transformative role in migration decisions. Families often send one member to the cities so that children can continue their education. Yet crowding is evident in urban schools, and many migrant children work to support their families instead of attending school. This creates a long-term cycle of limited mobility. Expanding inclusive education can break this cycle, particularly in informal settlements. Policies should consider flexible schooling models, community learning centres, and financial incentives to keep children in school rather than pushing them into vulnerable labour sites.

Healthcare facilities in cities are often unequal. Clinics are usually distant and costly, and the lack of documents or permanent addresses often restricts migrants’ access to services. Women face particular challenges in maternal care and reproductive health. For the upcoming government, improving primary healthcare in densely populated settlements is essential. Mobile clinics, community health workers, and affordable insurance models can address practical health challenges. Migration does not only change geography or location; it also alters patterns of disease, stress, and mental health, all of which require sustained policy attention.

The effects of rural–urban migration also have implications for the food system. In growing urban areas, the demand for food has increased with migration. However, this has also affected agricultural production in rural areas. This stress creates new vulnerabilities for migrants. Technological assistance, fair pricing systems, and accessible markets can reduce these stresses by strengthening the rural economy. At the same time, city authorities must prioritise improved distribution networks, price controls, and assistance to small-scale food distribution traders. A balanced food system can help stabilise the drivers of overall migration.

Digital technology has begun changing migrants’ urban experiences. Mobile banking, online employment platforms, and social media connect migrants with their villages and the global economy. These arrangements reduce socio-economic isolation, but they also expose migrants to challenges including misinformation, economic deception, and various forms of exploitation. The upcoming government should focus on digital literacy, safe economic transactions, and transparent job-matching platforms. By providing security within the digital landscape, policymakers can strengthen migrants’ overall resilience. Technology will provide the best safeguards if human vulnerabilities are understood comprehensively.

Migration also influences political participation. Migrants are usually registered in their own villages, but they reside in cities for years. This weakens their visibility in city governance and results in reduced representation in policy debates. Promoting updated voter registration, decentralised service delivery, and the participation of migrants can help change this imbalance. When those who build the city are able to participate, policies gain a more realistic foundation and become more attuned to marginal voices.

Migration is not an accident. It is a rational outcome of rural transformation and national development and must be addressed with prudence. It should be understood and reflected as a social process in urban governance, not treated as a temporary problem. The upcoming government should reform planning structures that recognise density, informality, and dynamism as features rather than flaws. Coordination between national and city authorities, the promotion of information-driven policy, and the incorporation of anthropological insights can help build an inclusive city.

Global experiences show that when rural–urban migration is supported by well-planned strategies and policies, it eventually contributes to overall growth while protecting migrants’ rights. Countries with sustained rural investment, balanced urban growth, and social security systems manage migration more effectively. Bangladesh can learn from these experiences; however, policies must be adapted to the local cultural context. Policy-level decisions should align with the everyday realities of migrants: garment workers in Chattogram, construction workers in Gazipur, and female domestic workers in lesser-known households in Dhaka.

Bangladesh is now at a critical juncture. Migration will not slow down soon; with rapid climate change, employment shifts, and demographic transitions, it is likely to intensify further. The long-awaited upcoming elected government should approach this inevitable issue with empathy and intelligence, rather than attempting to suppress rural–urban migration by framing it solely as a challenge. To make migration more balanced, the underlying reasons that push people to migrate must be addressed. Facilities and amenities in rural areas must be improved. Alongside economic concerns, sociocultural issues also need careful consideration. In both rural and urban areas, policies must ensure people’s participation, and interventions should reflect their voices and active engagement—not merely informed participation, but meaningful involvement throughout the entire process.

By prioritising housing, labour rights, transport, education, healthcare, rural development, and climate action, the government can reduce suffering and challenges while unlocking the country’s humane potential. The future of urban Bangladesh depends on how concerned bodies, including the upcoming elected government, listen to migrants who seek secure shelter in cities in pursuit of a better life.

Ala Uddin is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Chittagong. He can be contacted at ala.uddin@cu.ac.bd

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.