Can the Barind Tract survive its own agricultural success?

Stand in the middle of the High Barind in late April, and you are standing on one of the most geologically distinct surfaces in Bangladesh. The soil here is not the soft, grey silt of the active delta; it is an oxidised, iron-rich red—hard as concrete when dry, sticky as glue when wet. The heat radiates off the ground, often pushing temperatures past 35°C, while the winters dip below 10°C.

For centuries, this elevated Pleistocene terrace—an 8,720 square kilometre inlier sitting like an island within the Bengal Basin’s recent floodplains—was known for its harshness. It is crisscrossed by rivers, yet paradoxically remains one of the country’s driest regions.

Today, however, a drive through Rajshahi, Naogaon, or Chapai Nawabganj reveals a different reality. The landscape is lush, verdant, and productive. It sustains two to three crops a year, contributing significantly to national food security. But this “green revolution” hides a disturbing secret beneath the red clay: the water that fuels it is running out.

As the Barind Tract accounts for nearly 50% of the total agricultural groundwater use in Bangladesh, the region faces a critical reckoning. The water tables are dropping, the aquifers are stressed, and the very model that turned the Barind green now threatens to turn it dry once again.

The geography of thirst

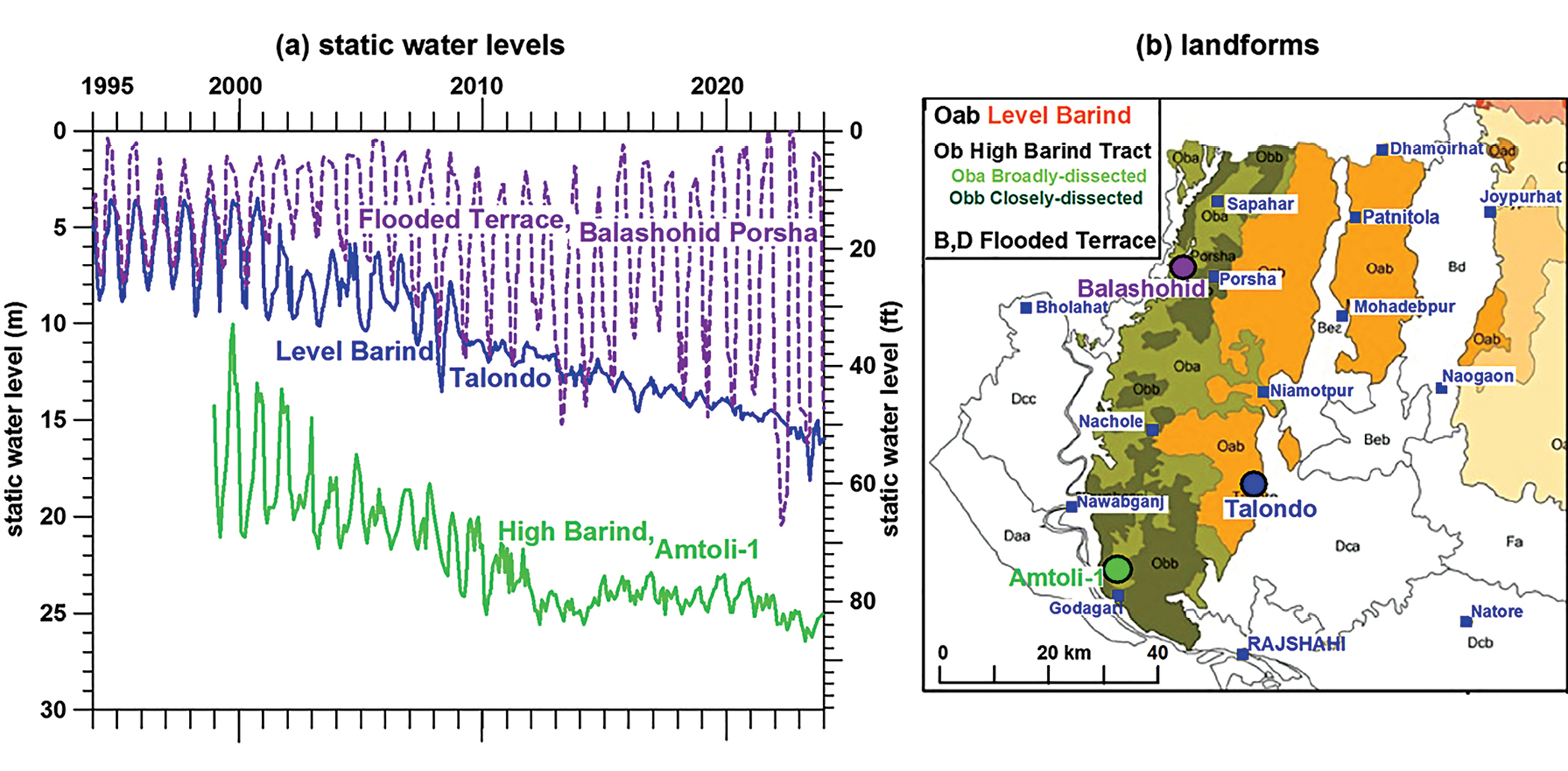

To understand the crisis, one must understand the land. Spanning most of the Rajshahi and western Rangpur divisions, the Barind is an ancient formation, older than the floodplains that surround it. Topographically, it is dissected and complex, which can be broadly classified into three distinct hydrological personalities, each reacting differently to the thirst of modern agriculture.

First, there is the Flooded Terrace, where the aquifer is buried beneath a relatively thin layer (3–12 metres) of fine surface material. Here, the monsoon floods—driven by rising rivers and runoff—provide a natural recharge mechanism.

Second is the Level Barind. These areas are nearly flat and undissected. While they occasionally flood during high-intensity rainfall, the precious groundwater here is locked beneath a thick “aquitard”—a 6 to 27-metre layer of clay that slows down water penetration.

Finally, there is the High Barind, the most visually striking and hydrologically vulnerable zone. Hilly and cut by narrow valleys known locally as bydes, this area sits high above the water table. The aquifer here is shielded by a massive 20 to 35-metre thick aquitard. Rainfall here doesn’t just soak in; it runs off rapidly through the bydes, leaving the groundwater reserves isolated and difficult to replenish, yet it does get replenished to a limited extent.

Historically, this geology dictated a single-crop economy. Farmers waited for the rains (1,250 mm in the west to 2,000 mm in the north), planted their monsoon rice, and hoped for the best.

The miracle that defied the UN

In the early 1980s, the global development community looked at the Barind Tract and saw a hydrological dead end. A 1982 study by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) offered a grim verdict: the aquifer system in the northwest was too complex and limited. They concluded it was suitable only for domestic drinking water, not for intensive irrigation.

Bangladesh, however, decided to gamble against the odds. In the mid-1980s, the Barind Multipurpose Development Authority (BMDA) launched an ambitious campaign to tap into the deep aquifers. They ignored the conventional wisdom that said the red clay was impenetrable. They utilised innovative engineering, including the “Inverted Well” design invented by Dr. Asaduz Zaman, to pierce the thick clay layers and access the water trapped below. Unlike a conventional well, where the pump is located within the well casing near the surface, the inverted well places the pump near the bottom within the screen section.

The intervention was nothing short of transformative. It was an engineering triumph that rewrote the economic destiny of millions. Farmers who once lived hand-to-mouth on a single rain-fed harvest began producing two, sometimes three crops annually. The hungry, brown landscape turned emerald green. Livelihoods improved, poverty rates dropped, and the Barind became a powerhouse of rice production.

But in defying the geological limitations, the region began writing a cheque its aquifers couldn’t cash.

The hydrogeological tipping point

Today, the bill is coming due. The Barind is suffering from “irrigation-driven depletion.” While the inverted well design successfully unlocked the aquifers for irrigation, it also created the capacity to pump them dry, posing a severe threat to the long-term viability of the region’s water reserves.

The crisis is not uniform. In the Flooded Barind areas, water levels have remained relatively stable over the long term, though they show increased seasonal fluctuations. The real emergency is unfolding in the High and Level Barind—the heart of the agricultural boom in Rajshahi, Naogaon, and Chapai Nawabganj.

The decline of the water table here tells a complex story of physics and geology. Initially, when the irrigation wells first began pumping, the water levels showed massive seasonal fluctuations, followed by a rapid, terrifying decline. This was the aquifer reacting under pressure.

However, in recent years, hydrographs show that the rate of decline has paradoxically slowed. To the untrained eye, this might look like stabilisation. It is not. It is a symptom of a fundamental shift in the aquifer’s nature.

As the water level dropped below the confining layer of the Barind clay, the aquifer transitioned from a “confined” system to an “unconfined” one. In a confined system, pumping releases pressure, causing rapid level drops. In an unconfined system, the water is drawn from the physical pore spaces of the soil (specific yield). The decline slows because there is more volume to draw from, but the total reserve is being physically emptied.

For decades, geologists viewed the massive clay layer covering the aquifer as a watertight lid, sealing the groundwater off from the surface. This assumption led to the belief that the aquifer was a finite, fossil resource that could not be replenished. However, the misconception that the Barind Clay is entirely impermeable has been challenged by recent findings.

The conceptual illustration of physical processes paints a radically different picture. The clay is not a monolithic seal but is instead riddled with a network of ancient cracks, fissures, and root channels. These “macropores” act as vertical pipelines, facilitating a constant, year-round recharge to the aquifer. This creates a complex feedback loop. As farmers flood their paddy fields for Boro rice, a significant portion of that water permeates the bunds and beds of the fields. It travels down through the clay fissures, eventually dripping back into the aquifer—a phenomenon known as “irrigation return flow.” In essence, the system is recycling its own water. While this process slows the decline of the water table, it does not stop it. The rate of extraction for water-hungry crops simply outpaces this combined natural and artificial trickle of recharge.

The way to sustainability

The question plaguing policymakers and hydrologists is simple: Is the damage irreversible? Are we witnessing the slow death of the Barind’s agriculture?

Answering these questions requires a deep dive into the hydrogeological nature of the Barind—a task only possible after decades of pumping and careful observation. This critical understanding has been unlocked thanks to meticulous long-term monitoring of groundwater levels and abstraction by Dr. Asaduz Zaman and Mr. Mehedi Hasan of the Centre for Action Research-Barind (CARB). Their data enabled Dr. Rushton to model the groundwater system of the High and Level Barind with unprecedented accuracy.

This detailed modelling offers a glimmer of hope, provided we are willing to change our habits. The findings were clear: the current trajectory is unsustainable, but the situation is not hopeless. The study concluded that groundwater use in these critical zones could be stabilised.

The magic number is 70%.

The models suggest that if total groundwater abstraction is reduced to 70% of current volumes—a cut of 30%—the aquifers can recover and sustain themselves.

Achieving this does not mean abandoning agriculture; it means reimagining it. The current dominance of Boro rice, a thirsty crop that requires thousands of litres of water for a single kilogram of grain, is the primary driver of depletion. The path forward lies in crop diversification. Replacing the water-intensive winter rice with lower-water crops like wheat, maize, pulses, oilseeds, and spices could achieve the necessary 30% reduction without devastating the local economy. These crops are not only less thirsty; they often command higher market prices and improve soil health.

While Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR)—artificial methods to force water back underground—is often touted as a silver bullet, the data suggests caution. Proponents point to systems like the one at the Amtoli-1 deep tubewell, where rainwater from a pump-house roof is fed directly into an inverted well. However, the volume of water directly recharged this way is negligible—less than 0.1% of the natural recharge occurring right now.

Paradoxically, the most effective recharge system is the agriculture itself. Massive volumes of water seep through the beds and bunds of rice fields during both the monsoon and Boro seasons. This water is slowly transmitted through the overlying clay into the underlying aquifer. This “accidental” recharge far outstrips any artificial MAR scheme proposed so far.

A race against time

The Barind Tract stands at a crossroads. One path continues the status quo: drilling more wells, pumping harder, and chasing the falling water table until the aquifer runs dry. This path leads back to the poverty and scarcity of the pre-1980s. The other path is one of adaptation. It requires the same boldness that defined the region’s development in the 1980s. Back then, the challenge was to get the water out. Today, the challenge is to keep it in.

The “Inverted Well” was the technological innovation of the 20th century for the Barind. Crop diversification and strict water governance must be the innovations of the 21st century. The red soil of the Barind has proven it can feed the nation, but it can only do so if we stop treating its water as an infinite resource and start treating it as a precious, finite inheritance.

The transition will not be easy for farmers accustomed to the rhythm of rice. But the science suggests it is the only way to ensure the Barind remains green, rather than returning to the barren, thirsty terrace of the past.

Dr. Mahfuzur R. Khan is an Associate Professor of Geology at the University of Dhaka, Bangladesh. He can be contacted at m.khan@du.ac.bd.

Dr. Ken Rushton is a Professor (Retired) at the University of Birmingham, UK. He can be contacted at kenrrushton@btinternet.com

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.