Missionaries in the war zone: Australian Baptists and the birth of Bangladesh

The Liberation War triggered an exodus of approximately ten million refugees to India and a further thirty million internally displaced. Given the extent of displacement, the international community mobilised to provide humanitarian assistance to Bangladeshi civilians.

Most research has focused on the actions of foreign governments and secular humanitarian non-government organisations (NGOs), such as the Red Cross. But what about non-state actors—that is, ordinary citizens? How did everyday people with no formal links to humanitarian NGOs help refugees?

My research is part of a growing scholarly interest in "everyday humanitarianism": the small acts that people commit to help others. In the case of the Liberation War, everyday humanitarianism involved Brits, Australians, Japanese and Americans (among others) donating cash and goods to aid organisations, lobbying local politicians to increase state support for Bangladeshi independence, and drawing public attention to war atrocities.

Historians of humanitarianism rarely examine the role of missionaries, particularly in post-colonial conflicts like Bangladesh. When missionary humanitarian work is acknowledged, it is often disparaged as a tool of evangelism and neo-imperialism. The true intentions of missionaries and missionary organisations are thus brought into question and presumed suspect.

In a recently published chapter in the edited collection Rediscovering Humanitarianism (Routledge, 2025), I use the case study of Australian Baptist missionaries who were based in Bangladesh to uncover their altruistic acts during this brutal conflict. While some of these missionaries left Bangladesh under direction from the Australian government, others refused to leave the country despite significant risks to their own safety.

My research reveals that the Australian Baptists who were based in Mymensingh provided material aid for evacuees in numerous ways. These included sheltering eighty Hindu and Muslim refugees, offering medical aid in neighbouring refugee camps, donating cash to displaced Garo tribespeople, and hiding refugees in makeshift bomb shelters during air raids. While this assistance may appear insignificant given the scale of displacement, it is important to remember that seemingly small acts of humanitarianism have the capacity to save countless individual lives.

What is distinctive about this research is that it considers how faith and spirituality facilitated, rather than impeded, the humanitarian efforts of these missionaries.

Australian Baptist Missionaries in Bangladesh

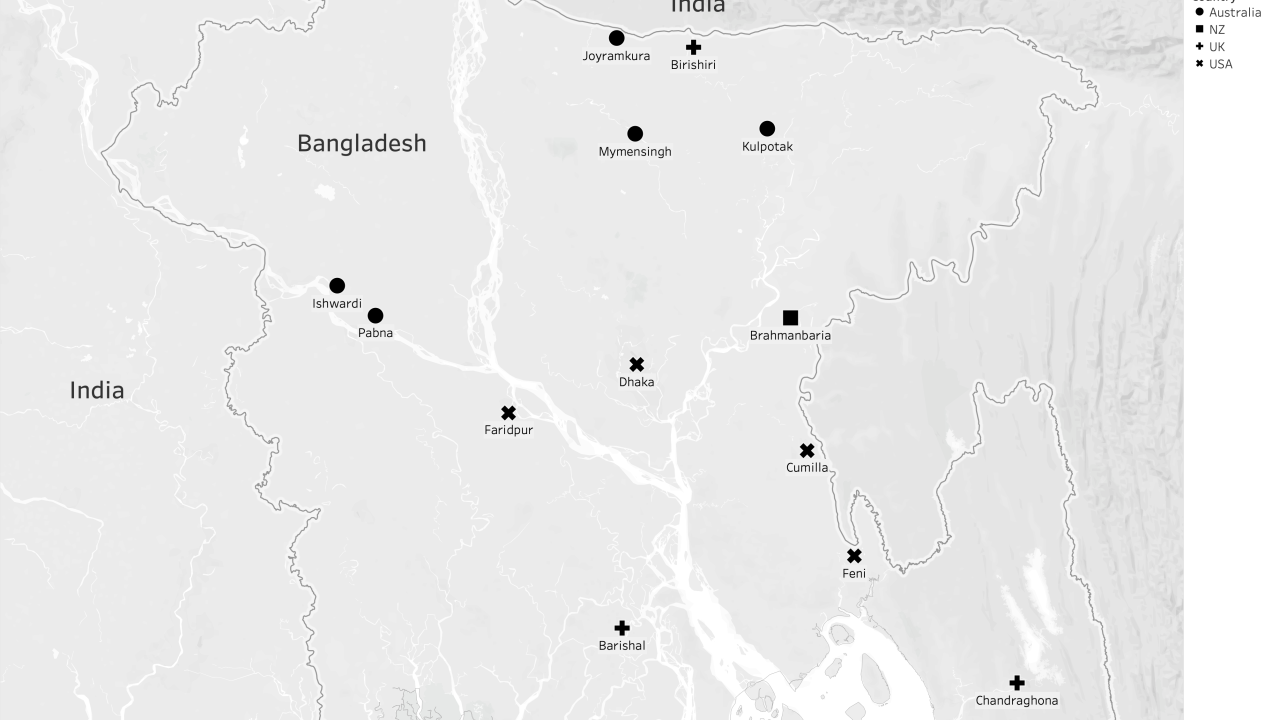

At the end of 1970, the Australian Baptist Missionary Society (ABMS) had 140 missionaries stationed in four countries and was subsidising Baptist missionary work in five additional countries. In Bangladesh, the ABMS had workers in Mymensingh, Kulpotak and Joyramkura. In this northern cluster, Australian Baptist missionaries worked alongside British Baptist and Anglican missionaries who were based in Birishiri and Haluaghat, respectively. In the west, ABMS workers were based in Ishwardi and Pabna, which had been an ABMS station since 1949 and was located north-west of the American Southern Baptist Convention station in Faridpur.

The ABMS had carved out a monopoly on missionary work in Pabna and Mymensingh, serving as the only Protestant missionaries in these cities, which had a combined population of 12 million people at the time. At the beginning of 1971, the ABMS extended its reach to Dhaka and worked collaboratively with American Baptist missionaries already there. However, with the outbreak of war, this operation was suspended until 1972.

When the war began, there were sixteen ABMS missionaries in Bangladesh, including eight single women and four married couples. As the war continued, some ABMS workers left Bangladesh, either due to planned furloughs, family emergencies, or because it was unsafe to remain in their assigned towns. However, three individuals—one married man and two single women—remained in Mymensingh for the entirety of the war and the immediate post-war months of reconstruction. These missionaries, Ian Hawley, Betty Salisbury and Grace Dodge, who were known internally as "the big three", remained in Mymensingh despite significant risks to their safety.

In 2019, I interviewed two of the three surviving former missionaries who experienced the entirety of the war: Grace Dodge and Ian Hawley, alongside his wife Barbara, who was in Mymensingh until August 1971. Alongside these interviews, my research analysed the ABMS archives, the personal letters and diaries of Grace Dodge and Betty Salisbury, as well as published materials—specifically the Australian Baptist newspaper, magazines and memoirs.

Australian missionaries (and those from other nations and denominations) offered efficient, cost-effective relief, which stood in marked contrast to the alleged waste, inefficiency and corruption that plagued many well-meaning but poorly administered humanitarian programmes run by governments and NGOs.

For example, in a letter to the ABMS, Betty Salisbury wrote that despite the influx of millions of dollars' worth of relief goods into Bangladesh, "it seems to disappear like water in sand and still hardly shows where it [donations] has been used".

Baghmara camp

By remaining in Bangladesh, Australian Baptist missionaries were able to provide tangible assistance that was targeted to the immediate needs of refugees. It should be remembered that during the war, foreigners were forbidden from entering Bangladesh. Only those who were already in the country could remain—and even then, often against the wishes of their home governments.

With foreigners unable to enter Bangladesh, international aid agencies therefore directed their humanitarian efforts to the refugee camps in West Bengal. The Indian government also prohibited foreigners from entering the refugee camps in the states of Assam and Meghalaya.

Within Meghalaya, Baghmara became one of the largest refugee camps. In a town with a population of 2,000 residents, the Baghmara refugee camp became home to 98,000 exiles. Yet foreign aid organisations could not assist these refugees.

However, Australian Baptists in Mymensingh found a way to assist the refugees based in Baghmara. This camp was significant to the ABMS for two reasons. First, Australian Baptist missionaries personally knew Garos who had fled to the camp. Second, Baghmara was merely eight miles from Birishiri, a base for British Baptist missionaries, including one Australian, Emily Lord, who was there on secondment.

As a trained nurse, Emily Lord offered medical assistance in the Baghmara camp from June to September. From her encounters with refugees there, Emily Lord relayed anecdotes to ABMS management. These on-the-ground stories proved valuable in eliciting donations from the Baptist community in Australia. In June, Baptist World Aid and Relief, the relief arm of the Australian Baptist Church, dispatched US$12,000 for Garo refugees, US$6,000 of which was raised through donations.

Sheltering

From October 1971 to January 1972, Australian Baptist missionaries in Mymensingh sheltered 80 refugees within their compound. Ian Hawley recalled in our interview that, at first, the hostel accommodated Hindus and later also welcomed Muslims and Christians.

Australian Baptist missionaries sheltered many, but their most significant intervention was providing three months of sanctuary to 18 Hindu girls and young women. The Hindu girls were trained to sew, enabling them to repurpose disused second-hand clothing, and they planted crops in the vegetable garden for the community. Australian Baptist missionaries gave the Hindu girls structure and purpose by providing a daily routine, training, and opportunities to develop skills in self-sufficiency.

In a recently published chapter in the edited collection Rediscovering Humanitarianism (Routledge, 2025), I use the case study of Australian Baptist missionaries who were based in Bangladesh to uncover their altruistic acts during this brutal conflict. While some of these missionaries left Bangladesh under direction from the Australian government, others refused to leave the country despite significant risks to their own safety.

In her interview and in her diary, Grace Dodge observed the challenges faced by Hindu girls during the war. She recounted to me that the girls "had been through some horrific experiences" and noted that they arrived with nothing. In her diary entry for October 23, 1971, Grace Dodge recorded that when the Hindu girls arrived, "their entire worldly goods filled half a small plastic bucket". When the girls arrived at the mission station, "they [the girls] said it was like arriving in heaven", according to the diary of Grace Dodge.

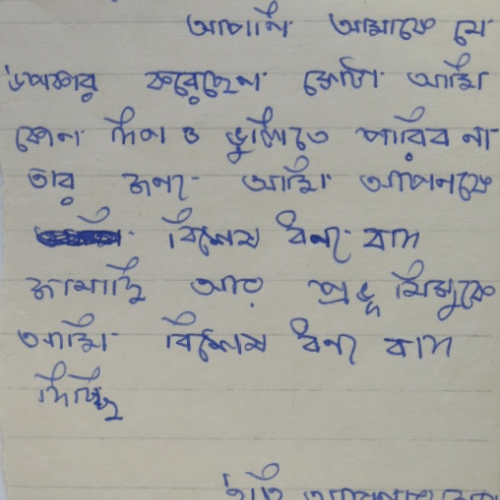

The significance and impact of Baptists offering shelter and protection was not lost on the refugees. In the weeks following the cessation of hostilities, the sheltered Hindu girls wrote letters of thanks and reflection to their protectors.

One girl, Ronju Shingho, came to the mission station after her brother had been murdered and her father feared for her safety. Ronju recalled in a letter, "Father came to know about this Baptist Mission and the way they are helping the girls… father said, 'for your safety and peace you need to stay in the mission house because they will give you clothes, food and you won't have any poverty, you don't have to feel the poverty'". Ronju wondered, "If you, the Baptist missionaries, did not help, then where would we be today? We would have been dead by starvation. So, we are thankful to God, and God will bless you".

When the Australian missionaries decided to open their hostel to refugees in mid-October, they planned to house twelve girls. It soon became apparent that refugee demand for the hostel beds far exceeded supply. By October 31, the hostel was already at capacity, housing 13 girls. By early November, the Baptist missionaries had accepted 18 girls "under great stress" and would soon begin turning away desperate women. In her diary entry on November 8, Grace Dodge noted that one of the girls the mission had turned away was subsequently "bashed up".

In her letter to family three days later, Grace Dodge repeated this observation and added this explanation: "We have 18 of them crowded into the hostel. We had planned to take only 12 but that is how it worked out. There are other very needy cases that we would like to take but cannot for the space. That one girl we refused to take got bashed up the other night".

Although it was not mentioned explicitly, the duplicated comments about the assault of the rejected girl suggest feelings of guilt and remorse about not being able to offer more to the girls in need.

Reconstruction

When Bangladesh was victorious on December 16, missionaries were already on site and could assist immediately with relief and reconstruction efforts. In the case of Australian Baptist missionaries, their greatest contribution was the reconstruction of the Joyramkura Hospital alongside the Swedish Red Cross from February to April 1972.

During the war, the hospital had been vandalised and looted, although the basic structure of the building remained sound. Given its proximity to the Indian border and the speed with which refugees were returning home, Ian Hawley recounted in our interview that "we needed the hospital going once again and we needed to do it quickly". The issue for the missionaries was securing supplies and trained medical staff. Ian Hawley travelled to Dhaka to persuade the Swedish Red Cross medical team to relocate to Joyramkura, while Grace Dodge and Betty Salisbury organised the delivery of medical equipment and supplies.

Rethinking the impact of missionaries

In a United Nations Information Paper released on February 18, 1972, report author Toni Hagen presented some "blunt facts" on humanitarian work during the reconstruction of Bangladesh. He wrote:

"Missionary groups are doing a wonderful job all over the world, as I know from my own experience in many countries. They generally embark on integrated rural development, vocational training and education. This requires long-term projects. In fact, such long-term projects can only be afforded by missionary groups. Only they can afford their personnel to stay for generations in the field under minimal administrative costs."

Not only did the UN articulate the value of missionaries in providing relief and rehabilitation in Bangladesh, but it also argued that only missionaries were able to provide the long-term, structural development necessary to help rebuild Bangladesh. This extract from a UN bureaucrat is a rare example of secular humanitarians celebrating the contributions of missionaries to relief work. I would add that the Baptist missionaries examined in this research had the linguistic capabilities (fluency in Bangla; conversant in Garo) to communicate with refugees, a skill not shared by many secular or faith-based humanitarian NGOs.

The missionaries also had deep, trusting relationships with their community because they had lived in Mymensingh for an extended period, including during the war. Because of their loyalty and commitment to Mymensingh, the missionaries gained respect and admiration from locals, which in turn increased their access to the community. Although Hagen wrote about missionaries in a non-conflict context, it is the presence of missionaries in warzones that enables them to develop the relationships necessary for long-term development and reconstruction in the post-war period.

In my interview with Grace Dodge, she told me that after the war the Baptist missionaries started to wear traditional dress rather than Western clothes. This change in behaviour reveals a cultural transformation: from outsiders to committed members of the Bengali community. It also indicates an awareness of past power imbalances and acts of cultural imperialism.

This research does not seek to obscure past wrongdoings of missionaries. Indeed, the historical record is well versed in these critiques. Rather, this research offers a recognition of the humanitarian contributions of missionaries. While most of the foreigners fled for safety when war broke out, some missionaries stayed to offer assistance and protection to the most vulnerable. Missionaries may attract criticism for their evangelism, but it is this same commitment to faith that guides them in times of crisis to help the needy.

Rachel Stevens is a Lecturer in History at the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments