Promises aplenty but trade gap still wide

Bangladesh could not gain from the zero duty benefit offered by India six years ago as the neighbouring country also imposed a host of tariff and non-tariff barriers that negated the original gesture.

Even without any free trade agreement, countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Myanmar and Sri Lanka have higher exports to India than Bangladesh.

In 2011, when India extended the duty benefit, Bangladesh accounted for only 0.1 percent of the neighbouring country's imports. That ratio now stands at 0.2 percent.

Following then Indian prime minister Manmohan Singh's visit to Dhaka in September 2011, the neighbouring country's government extended duty-free benefits to all Bangladeshi products save for two alcoholic beverages.

But in the following year, the Indian government imposed a 12.36 percent countervailing duty on Bangladeshi apparel shipments, the country's main export item.

Countervailing duties are the tariffs levied on imported goods to offset subsidies made to producers of these goods in the exporting country.

“Our garment export to India would have been way higher had there been no countervailing duty in place,” said Farkhunda Jabeen Khan, director of MAKS Attire, which exports to India.

India's apparel market is worth nearly $40 billion a year, according to Khan. “By all means it is a substantial market,” she added.

Pran-RFL Group, one of the largest exporters to India from Bangladesh, saw its exports to India edge up a little after the duty-free benefit, said its Marketing Director Kamruzzaman Kamal.

India accounted for 35 percent of the company's export receipts of $184 million in fiscal 2015-16.

But, there are non-tariff barriers still in place, such as the non-acceptance of testing certification of the Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institution, he said.

Currently, India accepts BSTI certification for 14 Bangladeshi products, and most of the food items are left out from this list.

“We have to face a lot of challenges because of this,” Kamal said.

Since the BSTI certification is not accepted, the Indian side takes the samples from almost all consignments at the land port and sends them to the central labs for testing. “This process is time-consuming.”

The goods are left in the land ports for many days without any care, as a result of which the quality of food items like juice, biscuits and spices sometimes deteriorates, he said, adding that the cost of shipments goes up too.

Bangladesh's jute exporters are the latest to feel hard done by due to the neighbouring country's anti-trade stance. In January, India imposed anti-dumping duty ranging from $6.30 to $351.72 per tonne on import of jute and jute goods from Bangladesh and Nepal.

The anti-dumping duty, which is a protectionist tariff that a domestic government imposes on foreign imports that it believes are priced below fair market value, has been imposed for five years.

India accounted for about 30 percent of Bangladesh's jute and jute shipments worth $919 million last fiscal year.

“We want to reduce the gap in trade between Bangladesh and India,” said Taskeen Ahmed, president of the India-Bangladesh Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

During Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's visit to New Delhi from today, the issues of countervailing duty, BSTI certification and anti-dumping duty will be discussed.

Export of garments and pharmaceuticals in bulk can reduce the trade gap between the two countries, Ahmed said.

“During the visit, we will also seek Indian investment in Bangladesh so that the trade gap is narrowed,” Ahmed added.

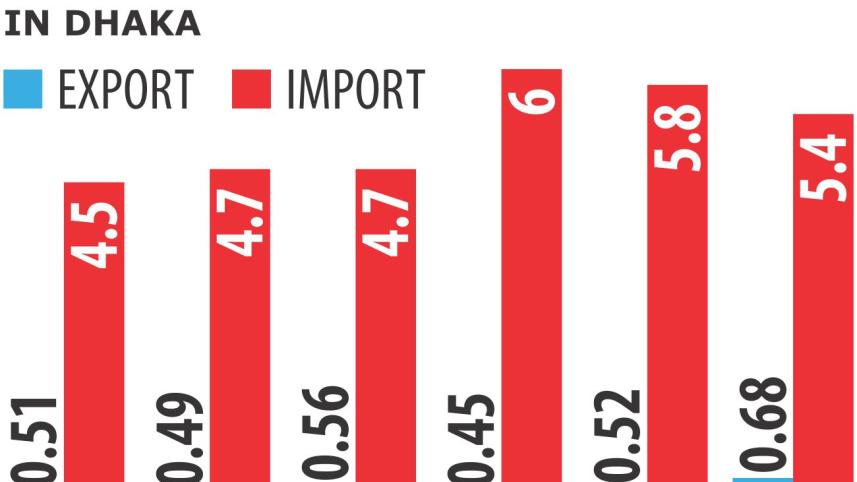

Bangladesh imported goods worth $5.45 billion from India and exported goods worth $689.62 million in fiscal 2015-16, according to data from the Indian High Commission.

In fiscal 2014-15, imports stood at $6.03 billion and exports $527.16 million.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments